By Barry Faguy, WSF Referees and Rules Committee

We now move to our second and final contribution regarding ‘Explanations’—essentially dealing with what you should or should not say to players to explain your decisions when you’re officiating a match. Last month we dealt with explanations regarding the first three topics of swing, wrong-footing, and ‘ball’ interference. Now, let’s look at even more fun and games.

Regarding ‘position of advantage’

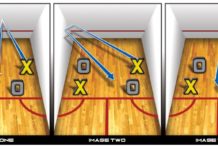

We dealt with this concept more fully in a column a couple of months ago, but it’s worth touching on again in terms of Referee explanations. The idea refers to situations where the incoming striker’s poor previous return is often held against him or her when that previous return has set up the opponent in an advantageous position—a position which then immediately becomes interference for the striker trying to get to the ball.

Like wrong-footing, ‘position of advantage’ situations are also routine occurrences— and thank goodness that most instances don’t result in an appeal (because they happen an awful lot!). If however, an appeal is made, the unfortunate instinct is to want to punish that incoming striker. Indeed, many mistakenly believe that the rules demand that the striker get a No Let—and that is particularly true if the return is the least bit tough to make. Well, in fact the rules say quite the opposite. They clearly require the Referee to simply consider these four words: “…but for the interference”—when asking whether the incoming striker would have been able to make a good return.

So, unfortunately we often hear these inappropriate gems: “You put yourself in that bad position,” or “You hit a bad shot,” or “You must go around your opponent,” or worse, “You created that interference.” It’s a primitive instinct to want to hold the striker’s previous poor returns that ‘caused’ the problem against him or her—but you must rise above it.

What can accurately be said to correctly justify a No Let for ‘position of advantage’ situations are the following: “You could not have reached the ball,” or “You did not make every effort to get to and play the ball.”

Regarding lack of audible appeal

The concept involved here centers around the point that the rules specify that the ‘correct’ method of making an appeal is audibly. But we need to note that the rules also give wide discretion to the Referee as to what can be accepted as an appeal. Because that appeal is often legitimately delayed by a collision or fall, or because communication is sometimes difficult—other acceptable options include a raised hand, racket, eyebrow, or just a ‘look’. Of course, it’s worth noting that you should always take care to be sure that the player is indeed asking for a let—and that the lack of an audible appeal is not because the player is actually conceding the rally.

Given the initial wording, unfortunately some Referees take a zero-tolerance approach and have justified a No Let with: “You didn’t say the word ‘Let’.” Some might also omit consideration of the circumstances (like a fall) and declare: “You didn’t appeal immediately.” Both of those are unnecessarily nit-picky—and incorrect to boot.

More accurate explanations might include: “You played through the interference” (12.7.3), or where the striker waited to see the outcome of a return: “You appealed too late” (12.5.2). And when you are uncertain as a Referee, the player should be given the benefit of the doubt.

Regarding non-striker appeal

Our final concept has to do with who exactly can make an appeal. The rules state that either player may appeal for certain noninterference issues (distraction, broken ball, etc)—but when it comes to interference, generally, only the striker may appeal (12.5.2).

I say ‘generally’ because a convention exists when it comes to ‘access’ interference. Given the rapid pace of the game, the rapidly incoming player (not yet technically the striker) often makes an appeal before the ball has actually reached the front wall—the point where the changeover from striker to non-striker technically occurs.

A referee who doesn’t understand this might incorrectly say: “You were not the striker.” The fact is that modern player speed has resulted in a convention that allows the appeal, rather than issuing a pedantic dismissal. (Word has it that this issue might specifically be addressed by an appropriate inclusion in the next iteration of the rules.)

There is a subtlety here that needs to be appreciated. The convention referred to above does not apply to those cases when the legitimate striker accepts interference and plays through—and that action simultaneously throws off the opponent. There is no allowable appeal there, and indeed here, you could use that “You were not the striker” phrase. What we are talking about are those cases where the legitimate striker, having finished hitting the ball (with it not yet having reached the front wall), is now in the way of the incoming player’s access.

So, avoid dismissing the appeal too lightly on that basis alone. Acceptable explanation (if true, of course) would be something like: “You would not have made a good return.”