By James Zug

By James Zug

This summer Henri Salaun and Hashim Khan both died. It was like John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, connected by their years together battling each other and at the same time fomenting the American Revolution and building the United States and then, fifty years to the day after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, they both passed away.

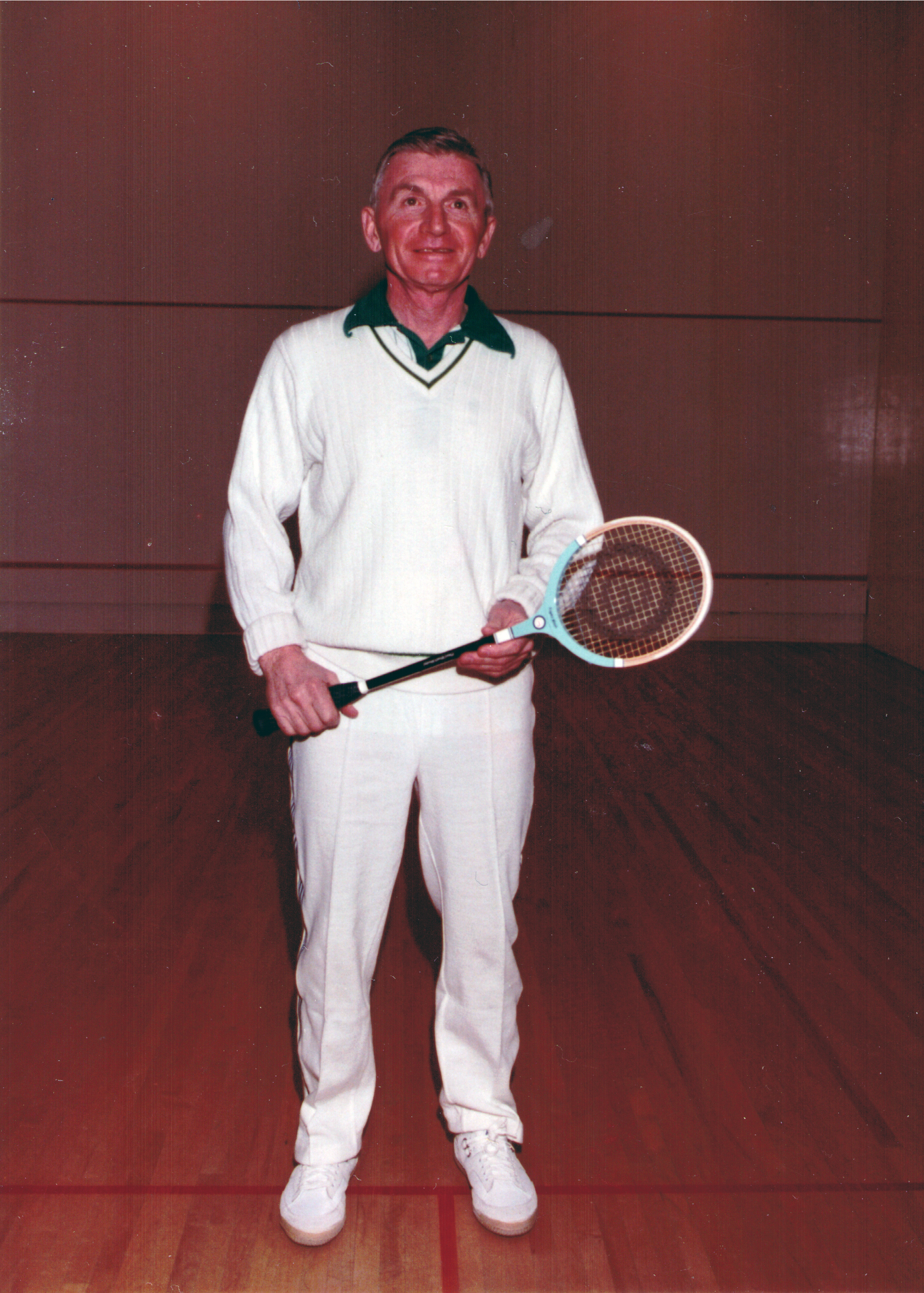

Salaun and Khan. Their names and their histories rhymed. They were both exemplars of the American dream: born in other countries, becoming U.S. citizens, raising their families here, parlaying their squash achievements into a career in the game. They were both incredible champions, both members of the inaugural class of inductees into the U.S. Squash Hall of Fame in 2000. They were both extremely competitive and focused. They were both brilliant counter-punchers, short, speedy retrievers. They both played all of their lives, literally not leaving the court until infirmity forced them to when they were very old.

Like Adams and Jefferson, they were also intertwined by one of the most famous and important matches in U.S. squash history, the finals of the inaugural U.S. Open. This spring US Squash had informed them that they were to be the honorary chairmen of the 2014 Delaware Investments U.S. Open in acknowledgement of that magical moment sixty years ago when they played in the finals of the first Open. Plans were in motion to bring them both to Drexel in October to celebrate this milestone. Then, ten weeks apart this summer, they both died.

Henri Salaun, born in France, a refugee arriving in America in 1940, Deerfield and Wesleyan, was a surprise finalist at the 1954 Open. And then he won it. He beat Hashim Khan that Sunday in January in New York. It was the first tournament loss that Khan had ever suffered.

Henri Salaun, born in France, a refugee arriving in America in 1940, Deerfield and Wesleyan, was a surprise finalist at the 1954 Open. And then he won it. He beat Hashim Khan that Sunday in January in New York. It was the first tournament loss that Khan had ever suffered.

Salaun captured four U.S. national singles titles (losing a further five times in the final—no other male had ever played in nine finals until 2014 when Julian Illingworth did it). He also won six Canadian national singles titles. He never stopped playing either, notching twenty-six U.S. masters singles titles before it was said and done. He died in June at the age of eighty-seven.

Hashim Khan was the most famous squash player ever. There was a huge flurry of attention when he died in September at the age of one hundred: the New York Times, Washington Post, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Atlantic Monthly and NPR all did obituaries. It exactly mirrored the media attention for his first visit to the U.S. for the 1954 Open.

In between, Khan transformed squash in America. By dint of his magnetic personality and his willingness to travel to any club anywhere to give an exhibition or opening a court, Khan was the ultimate squash proselytizer. The game took hold all across the country, city after city, in some significant part because this celebrity, this engaging person and brilliant player, was in town.

He also helped breathe fresh air into the game: an Asian, a Pashtun and a Muslim, playing on courts where normally only WASPS previously trod. His story revealed the egalitarian aspect of this sport, any sport. Here was a kid born to poverty, learning to play squash barefoot in open-air courts and when he came to America, the first day he played squash, it was at Merion Cricket Club and the first tournament he played in, it was at the University Club of New York. He really was the Jackie Robinson of squash.

He also helped breathe fresh air into the game: an Asian, a Pashtun and a Muslim, playing on courts where normally only WASPS previously trod. His story revealed the egalitarian aspect of this sport, any sport. Here was a kid born to poverty, learning to play squash barefoot in open-air courts and when he came to America, the first day he played squash, it was at Merion Cricket Club and the first tournament he played in, it was at the University Club of New York. He really was the Jackie Robinson of squash.

Khan didn’t win the 1954 Open title, but he won three more, the last in 1963 at the age of forty-nine. Thus, he was the oldest winner of any U.S. national open singles championship in history, surely yet another record of Hashim Khan’s that will never be broken.

A witty and attentive teacher, Khan always gave good advice. Keep eye on ball was his most famous; Josh Easdon and Beth Rasin used it as the title for their documentary on Khan. But another one I loved was “take big step.” Hashim Khan, he took the biggest step of all.