By James Zug

If the British Open is the church of squash (hallowed but lately not as central to our lives) the United States Open is the economy of squash. In the 40 times the men’s event and 16 times the women’s event have been staged, the Open has seen outsourcing—three dozen different tournament directors before U.S. Squash brought it in house, for the first time, in 2011; it has seen deficits—2007 edition in the Roseland Ballroom; it has seen flashy growth—at the Palladium in 1987; and decline—twice gaps of three years for the women.

But most of all, the U.S. Open is innovative. It was the first national racquet sport tournament in the country to go open, a few months before badminton and 14 years before tennis (only ping-pong’s U.S. Open is older, founded in 1931). It was the first pro men’s tournament in the world to use a 17-inch tin and point-a-rally scoring, now both standard.

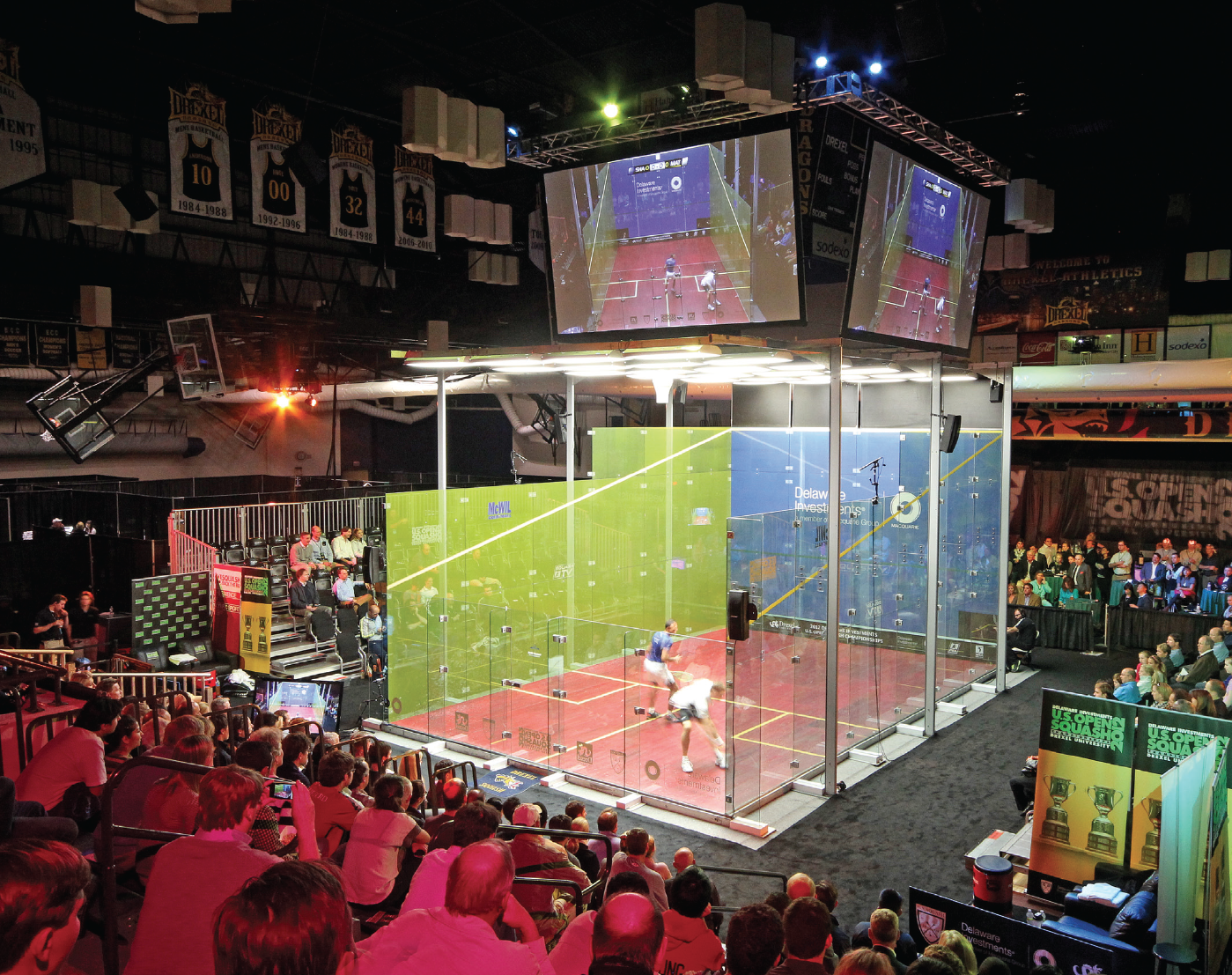

The 2012 Delaware Investments U.S. Open followed in that tradition by doubling down on interactivity. In between games on the two dozen video screens at Drexel’s Daskalakis Athletic Center, including the four-sided JumboTron, you could text or tweet responses to various questions—who will win this match? Is this a let or a stroke?—or even pose questions: “What do you eat after a match?”— or vote on referee’s calls on a replay of interference. Instantly you could see the votes tabulated. Sometimes a “fan-cam” appeared, showing dancing, waving spectators. Players tossed signed balls into the crowd after matches. Staff shot shirts and hats toward boogieing sections. You could download the U.S. Open app onto your smartphone and follow live scoring, especially handy if you were watching the men on the glass court and the women downstairs on a regular court (the women came up to the glass for the quarters onwards).

Yes, you could, in the interactive expo area, bang on the radar gun like last year. Trevor McGuinness, one of the hardest hitting doubles players, recorded 155mph, and after sweeping the hair from his eyes, he said that he wanted to try it with a doubles hardball.

Interactivity of an old-fashioned kind also happened behind the front wall. Conor O’Malley, the tournament director, expanded the usual ignored space into a floating, free-flowing milieu where you could stand by a bar or sit at high tables or in regular seats. Because the players had access to this space and could stand and watch, it enabled the Open to become the most social and intimate of any pro tournament I’ve been to: players, fans, coaches, referees—all with the best view of the McWil glass court.

U.S. Squash solved the main disappointment from last year: bigger crowds.

They advertised a two-page spread in Philadelphia magazine. They not only threw up billboards around town but hung banners from lampposts all the way down Market Street till you smacked into William Penn atop City Hall. They wrapped a 300-plus Junior Championship Tour tournament at Drexel and Penn that first weekend; the national intercollegiate doubles was again in town; the Annual Assembly brought in dozens of key decision-makers; NUSEA not only hosted a board meeting at the Open, but had an elite player event—the Urban Development Squad—at SquashSmarts, which meant an even larger number of urban squash players in the stands (especially during Kids Day when Philadelphia public school kids attended matches for free). Because of deep outreach, area clubs and alumni groups held evenings at the Open. An active young professionals committee networked and made sure that Philadelphia, the second largest district in U.S. Squash, supported the event.

It worked. More than 900 people attended the finals—the largest crowd in Open history.

All of last year’s sponsors reupped and a bunch of new ones jumped in. Drexel proved again to be an outstanding partner. John Fry, Drexel’s president, was around a lot, though not as much as athletic director Eric Zillmer who played every morning on the glass court and came every evening to watch. Drexel helped produce snazzy videos on the Open, which ran on the Internet before the event and on the video screens during breaks. One video, finished after the Open, featured most of the men and women players running up the steps of the Art Museum, a la Rocky and Ramy Ashour singing to “Eye of the Tiger.” Mario, the Drexel mascot, revved up the crowd, the Drexel ROTC cadets ushered in the finals with a precise color guard, and dozens of students worked on the tournament staff.

Lastly, total prize money was $185,000. Ashour received $16,625 and Nicol David $10,830. Purse equity is coming, as are larger payouts—U.S. Squash’s goal is to have a $1 million purse in ten years.

It always helps, though, if the product is good, and the 2012 edition was pretty amazing. More of the matches went to five games, especially later in the week, than in any previous Open. Sheer excitement and drama, night after night.

For the women, the storyline was simple: could Nicol David breakthrough and capture the one major title left missing from her curriculum vitae? David is reaching the apogee of her career, turning 30 next August. By one measure she is far and away the most popular squash player in the world: she has 28,300 followers on Twitter. That is equal to the top 20 male pro players combined. She is constantly pushing back the upstarts. That grind—constantly fighting to stay at No. 1—is wearying, her longtime coach Liz Irving told me. She’s a giver: she spent an afternoon before the start of her Open campaign out at SquashSmarts, giving clinics and working with young players. She’s made some personal changes: after sharing an apartment with Aisling Blake for years in Amsterdam, she just got her own place.

Coming to Philadelphia, David had lost in two successive tournaments—in the finals in her home event in Malaysia to Raneem El Weleily and then in the quarters of the Carol Weymuller to Alison Waters. Losing two in a row hadn’t happened to her in over three years.

In the semis, David faced Joelle King. Since moving from Montreal back home to New Zealand a year ago, King has steadied her own life. She’s gotten engaged to Ryan Shutte, a South African cricketer and gotten a dog, a golden retriever. With life calm at home, she has reached the quarters of the British Open in May and the finals in three other tournaments this year. Turning twenty-four just before the tournament, King slashed through the qualies and all the way to the semis (upsetting Jenny Duncalf in the quarters in five) where she fought David hard for 83 minutes, coming back from a 0-2 deficit to force a fifth game. In the fifth, she was up 6-0, just five points away from putting a nail in David’s career coffin. Instead, David reeled off ten straight points, nicking balls on all three walls.

Lucky in a way to reach the finals, David again faced El Weleily, who is now solidly the second-best woman in the world. She’s displaced Jenny Duncalf, who has a hairline stress fracture on the top of her left foot. El Weleily didn’t look terribly comfortable herself in Philadelphia, losing one game in each of the first two rounds and two in the semis to Massaro (who had just beaten her in the Weymuller). But El Weileily appeared very unruffled in the finals. She scrambled back from a 6-9 deficit in the first, only to squander a game ball in the tiebreaker and lose it 14-12. A few years ago, that would have deflated her confidence greatly and she would have given way quickly to David. Here, she walked off court with nary a grimace. In the second she played with verve and vigor, took it strongly, and she was up 6-2 in the third.

Suddenly, just like in her semis against King, the match switched in David’s favor. David nabbed the next nine points in a row and in the fourth she cruised to a 11-6 game. Afterwards, El Weleily was disappointed. “I started thinking about winning, when I was up 6-2, and that’s the worst thing you can do.” David was mystified about her streaky play (she’s so fleet of foot she can make up for sloppy mechanics), appreciative of the many flag-waving Malaysians in the crowd and clearly relieved at finally winning the U.S. Open. She didn’t know that she had also passed Sarah Fitz-Gerald as the all-time winningest player on the WSA tour with her 63rd title.

The Open, in another innovation, was truly open this year. Emulating the golf U.S. Open, anyone could try to get into the main draw by entering the pre-qualifying draw held over the summer. Amy Gross, a leading amateur player in Philadelphia, made it through, giving her a spot in the regular qualifying draw; she lost in three to Camille Serme. Other Americans also struggled in the first round of the qualies: youngsters Sabrina Sobhy, Elizabeth Eyre and Maria Elena Ubina lost in three; veteran Latasha Khan in four; and national champion Amanda Sobhy succumbed in a five-gamer. Kristen Lange had the wild card entry into the main draw, where she lost to defending Open champion Laura Massaro, taking until the second game to get off the mark.

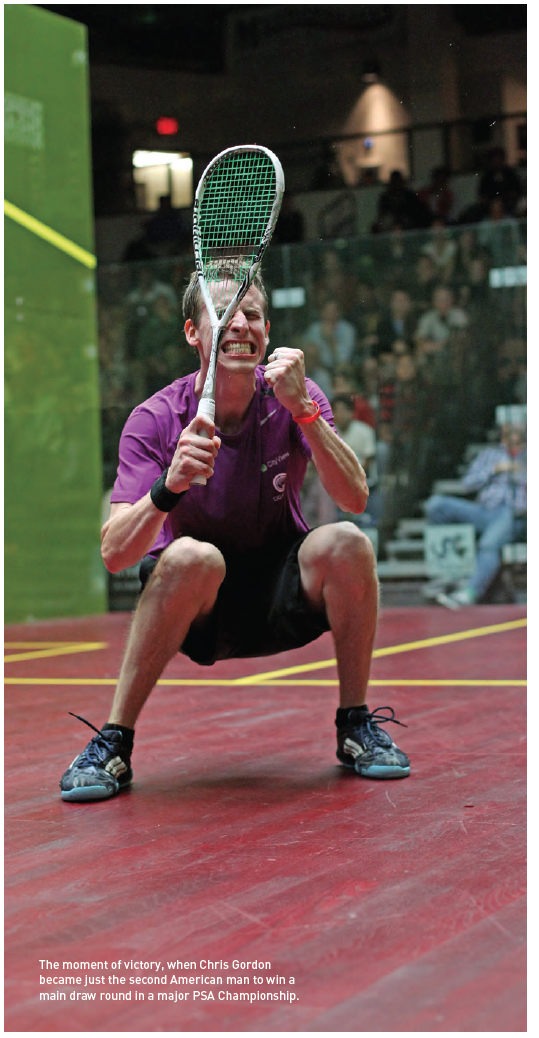

For the male wild card, it was a vastly different story. For the first time in his long career, Chris Gordon beat a top-twenty player and won a match in a World Series main draw. Gordon, like David and King, has found new strength in a new home. He now lives in Queens, near CityView and training with other New York City-based pros like Alister Walker and Bradley Ball who in turn had been playing with Hisham. “I’ve been sticking with them and they are great players, so that has given me confidence,” Gordon said. This summer he did a couple of monthlong training sessions with coach David Pearson in England. “He’s a racing snake now,” Pearson joked, pointing to Gordon’s newly slimmed-down frame. “He’s taken off that bulk he got from weightlifting too much.” (Gordon used to be sponsored by Max Muscle in West Harford, CT.) Now 26, Gordon is looking to lift the trajectory of his career—his highest ranking, 65, came five and a half years ago. A friend from his Hartford days, forward John Mitchell, recently made his breakthrough into the National Hockey League at age 26. Gordon is keen to emulate him.

Hisham Ashour was the perfect opponent. The Egyptian has been coaching at Pyramid Squash in Westchester and was seen running from Penn where he was coaching juniors to Drexel with his squash bag on his back, arriving ten minutes before his match was to begin. Ashour loves quick points and his impatience got the better of him. Gordon, looking more relaxed and confident than ever before, blew four game balls in the third before clinching it 13-11 and then let a 4-1 lead in the fourth go to waste. “In the fifth, I kept saying that this kind of opportunity only comes around a few times,” Gordon said. “I tried to be positive.”

Gordon came back down to earth in the next round, losing in 40 minutes to Karim Darwish. But for one night he was on top of the world. “This is the best moment of my squash life,” he said afterwards. He got back to his hotel room at 12:30am but was so amped up he couldn’t fall asleep till after two in the morning.

It was a great win that placed Gordon in rare company. Julian Illingworth, the previous American to win a main-round match at the Open, had beaten Clinton Leeuw in the first round of the 2010 Open in Chicago, before losing in four to Olli Tuominen. But Leeuw never got above 90 in the world. Before that it was 1994 in Providence when Jamie Crombie beat Tony Hands, before losing to Peter Nicol, but at the time Crombie, a U.S. citizen, was playing for Canada.

No, what Gordon’s victory recalled was the 1986 Moussy U.S. Open in Houston, when Ned Edwards beat Hiddy Jahan (eighth in the world at the time) and Mark Talbott beat Kelvin Smith (ninth) to reach the quarters. (Edwards lost to Ross Thorne, Talbott to Phil Kenyon.) Yes, the matches were in a 20-foot converted racquetball court—the Times of London wrote that “The U.S. Open is a committee’s conception of a squash tournament. It is played on a converted racketball court with an international softball to American hardball rules and scoring.”

Still, two Americans winning mainround matches, both over top-ten players? Coming soon, again, we hope.

The other Americans in the qualies played hard but had little to show for it. Illingworth beat countryman Dylan Murray in three and then squandered a match ball in losing a massive, 90-minute heartbreaker, 14-12 in the fifth, to Amir Atlas Khan. Todd Harrity nipped a game off Alan Clyne, and Chris Hanson and Graham Bassett went down in three, though both stayed on court for a full half hour. Besides Illingworth’s epic, the other excitement in the qualies was John White, former World No. 1 and Drexel coach, giving it a go against Miguel Angel Rodriquez. All three games were very close, but Rodriguez hopped, skipped and jumped (and dived) through. He beat Sidd Suchde, former Harvard star, and then had another rousing, popcorn-in-hot-oil treat with Amr Shabana, losing in three, including 15-13 in the third.

As the week progressed, matches seemed to be either very short or very long. Steve Coppinger had just started the so-called Paleolithic diet, based on what hunter-gatherers ate thousands of years ago. After the qualies, he had no energy left against Cam Pilley. He gave up a mastadon- egg in the first game and didn’t win a point until the third rally of the second game. Coppinger did finish with more total points than Olli Tuominen, the Flying Finn who had a left calf injury and garnered just six total in his laydown to Greg Gaultier.

On the other hand, seven main-round men’s matches went the full distance. In back-to-back quarterfinal matches, we saw Ramy Ashour and Peter Barker get to 9-all in the fifth and then two hours later Amr Shabana and Nick Matthew also reached 9-all in the fifth. Matthew was down 2-1, 7-4 before he found his rhythm. Shabana, with his shirt tightly tucked in, looked as fit and focused as ever in his career, but Matthew just barely was better.

Talk about exhilaration. With an overflow crowd (this was the night of Bob Callahan’s induction into the U.S. Squash Hall of Fame), nothing could be better than seeing four of the best players in the world going at it hammer and tongs for almost over three hours.

Two other five gamers involved Mohammed El Shorbagy. Business major at the University of Bristol, former world junior champion and the Egyptian darling du jour, El Shorbagy outlasted Cameron Pilley before going down to James Willstrop (Willstrop was up 10-0 in the fifth before El Shorbagy was able to get on the scoreboard). In turn, Willstrop, the number one seed, lost in three to Gaultier. The next day Willstrop said his legs were heavy and tired, that he couldn’t get moving.

That seemed to be Gaultier’s issue in the final. Ashour pushed and pulled him all around the court. For some on Twitter and watching on SquashTV, the match seemed too one-sided and good-natured (and a Twitter war of words broke out afterwards, involving Nick Matthew among others; Nick told me that night he was just sending out a tweet not changing the world) but in person it was not so much Gaultier not trying, as Ashour running rampant. He balletically bunny-hops around the court. His long, fluid strokes are classical—he even holds the racquet at the very end of the grip, wanting as much length as possible. His shotmaking is a thing of beauty: unpredictable, rambunctious and devastatingly accurate. He is like a ping-pong ball floating on an invisible gust of air.

Afterwards, a line of about a hundred fans snaked through the expo area, waiting for up to 25 minutes for an Ashour autograph. Now that is an innovation.