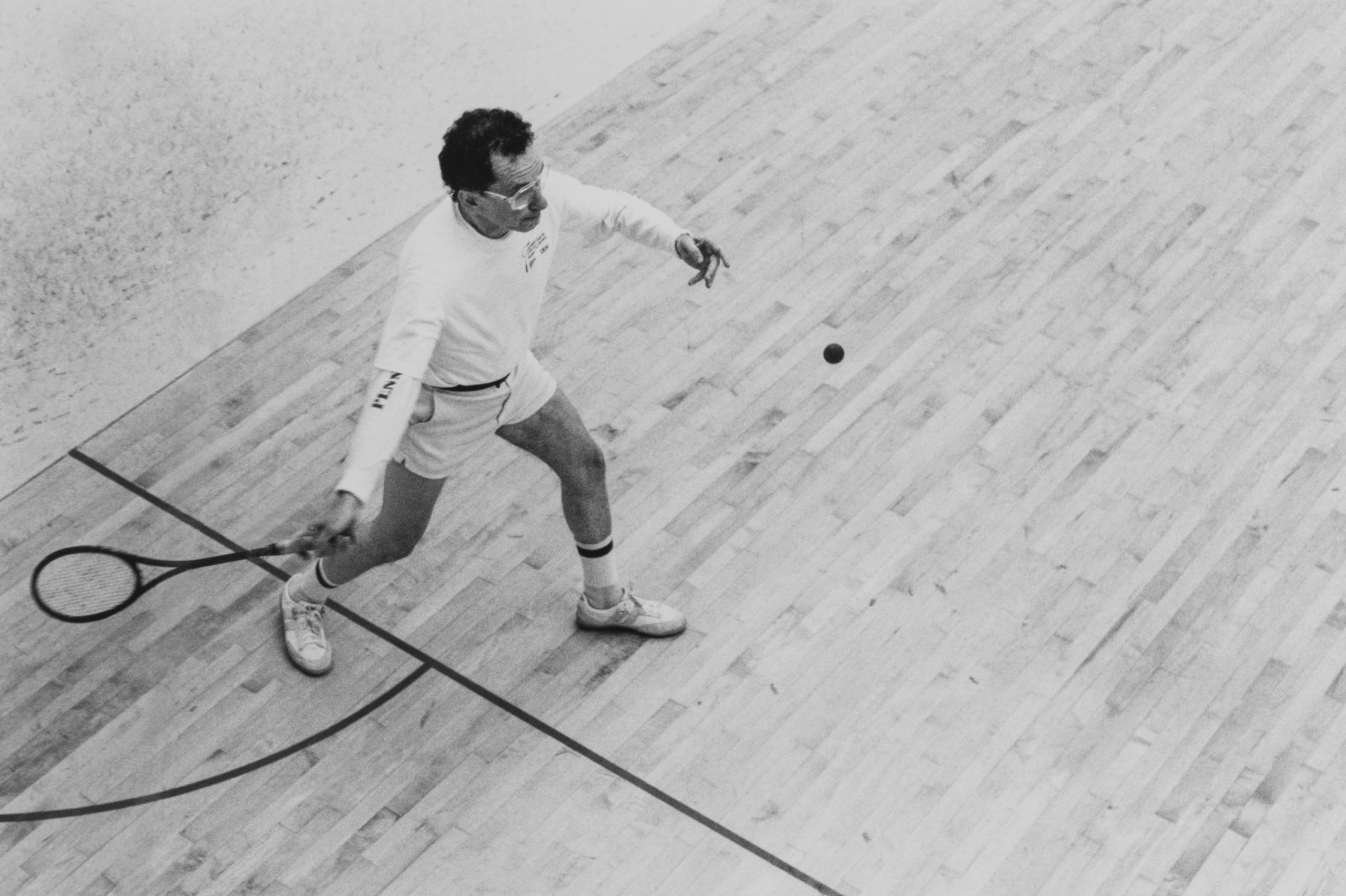

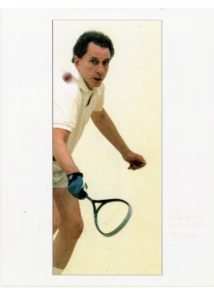

In mid-life Arlen Specter found that he needed an outlet. He had a stressful job—he was the District Attorney of Philadelphia, the fourth-biggest city in the country and awash in violent crime—and with his wife Joan was raising two children. He was aware of his weight and wanted to keep in shape. He was an avid sports fan: he had grown up in Kansas and was a third-string quarterback in high school. He tried squash while he was at law school at Yale in the mid-1950s. “He liked squash at law school,” said his wife Joan Levy Specter (they were married in 1953, two years after Arlen graduated from Penn). “It was his number-one activity. Squash was his release.” But after they moved back to Philadelphia, he had drifted away from squash.

In February 1970 Specter turned forty and decided to try squash again. “He wanted a great workout,” his son Shanin Specter said. “He needed to focus on something athletic. He was easily bored. He tried golf but found it boring. It took too long a time. He didn’t like chasing balls into the woods. In squash you rarely lost the ball. It came right back to you. And tennis, he played it but he felt there was too much wasted time. You had to go get the balls at the net or the fence. Running, lifting weights—it wasn’t interesting. Squash was more compact. It was competitive—there was a winner and a loser. It fit his personality. Squash is a very good sport for a guy with shpilkes [Yiddish for impatience or nervous energy]. He had shpilkes.”

Arlen Specter walked over to the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Located at the corner of Broad Street and Pine Street in downtown Philadelphia, the YMHA (now the site of the Gershman Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival) had squash courts and Specter began to play again. He never took a lesson. He developed a group of partners and soon was on court every day. A few years later he explored other public clubs like Clark’s Uptown at 15th & Race Street and the three courts at West Village (the former Philadelphia Country Club courts in Overbrook) and in later years the courts at the Sporting Club at the Bellevue Hotel on Broad Street.

Squash was a daily workout, not a social event. Specter often was quoted as saying, “I’m not a squash player. I play squash.” A couple of times he filled in for West Village’s C team in a league match. West Village also had a doubles court but Specter never fell in love with doubles, and in general he shied away from playing leagues and tournaments. “He felt he wasn’t a good enough player to play in any league,” Shanin Specter said. “He came into the game in his early forties. He usually played at public clubs—pay to play, no membership process. He didn’t play squash as a way to meet people or advance in society. And doubles didn’t give him enough of a workout. He loved the workout of singles. He’d play in a sweatshirt in order to make sure he got a sweat. He was never hung up about his game, worried about his strokes. It was about effort.” Late in life, Arlen and Joan Specter joined Philadelphia Cricket Club because Joan wanted to play golf there. Arlen could have started playing squash at PCC—it had a renowned squash program—but he continued to play at his public clubs. “He didn’t regard himself as elite or better than anyone else,” Shanin Specter said. “He wasn’t a country-club guy. He didn’t care about squash’s image. He cared about squash as a mechanism for fitness.”

Specter’s routine during the week was often to work all day and then go play in the late afternoon before a fundraiser; on the weekends he played early in the morning. Or vice-versa. It was always dependent on when he could get a game. He would always play five or six games, even if he or his opponent had already won the match in three or four. “Squash permitted him to let off steam,” said Steve Hamelin, an old friend and colleague dating back to the 1960s and one of his regular partners in the 1970s. “Some of the most thoughtful meetings we had were after we played squash. We’d talk about what was on his mind, how to proceed. It was an opportunity to talk in depth about an issue. Arlen’s style was to be aggressive on court. He’d try. He’d never give up, even when he knew I would beat him. He was tough. And if he couldn’t play squash, he couldn’t make it through the day. My guess is that he’d play 350 times a year. It was a part of his daily life. You see that kind of tenacity in distance runners sometimes but never in racquet-sports athletes.”

When Shanin Specter was a teenager, he played regularly with his father. Arlen kept a list of their matches on his locker at West Village, a long row of marks. “He was glad the day I beat him, when I was sixteen,” Shanin said. “He didn’t want to lose to anyone, but he was happy to lose to his son.” Arlen consistently attended Shanin’s high school matches at Penn Charter. “He believed in sportsmanship,” Shanin said. “I had a bad temper on court, and he wasn’t happy about it. He was convinced that sportsmanship was important. He delicately let me know that if and when I broke a racquet on purpose, he wasn’t going to pay for a new one.”

Once Arlen Specter was elected to the U.S. Senate at the end of 1980, he quickly found places to play in Washington. He joined the Capitol Hill Squash Club—the new public club on the Hill—and he also played at the Federal Reserve which had an old singles court (it was awkward for a while when he opposed the reconfirmation of the head of the Federal Reserve). Specter played with other Senators. He hit regularly with Carl Levin, a Michigan Democrat and Bob Packwood, an Oregon Republican. During one match, Senator Packwood smacked Specter in the face—Specter needed six stitches to heal.

Once Arlen Specter was elected to the U.S. Senate at the end of 1980, he quickly found places to play in Washington. He joined the Capitol Hill Squash Club—the new public club on the Hill—and he also played at the Federal Reserve which had an old singles court (it was awkward for a while when he opposed the reconfirmation of the head of the Federal Reserve). Specter played with other Senators. He hit regularly with Carl Levin, a Michigan Democrat and Bob Packwood, an Oregon Republican. During one match, Senator Packwood smacked Specter in the face—Specter needed six stitches to heal.

When he wasn’t battling Senatorial gladiators, there was a long line of staffers on the Hill with whom Specter played squash, people who worked for him or for other members of Congress. “He would just ask people if they played,” said Scott Hoeflich, who joined Specter’s staff in 1999 and served as his Chief of Staff from 2006 to 2011. “He enjoyed teaching new people the game. He loved to play. He’d call me at 5am on the way to his morning squash match and go through what we had to do. By the time he got to work, a fourth of his day was over. He liked structure. He liked the schedule. It helped him move around his day. Time was a commodity.”

Squash was a part of Specter’s love of sports. “He would have much rather have been a great athlete than a great elected official,” Joan Specter said. “If he could have played left field for the Phillies, he would have loved that.” When Specter arrived at Penn in 1948 he tried to major in sports broadcasting but was told they didn’t have that major, so he fell back on pre-law. He adored college football and avidly followed the University of Oklahoma football team—he had attended Oklahoma before transferring to Penn. He was a season-ticket holder for the Eagles and followed the Phillies and the Sixers. He called into Philadelphia sports talk radio shows. “I absolutely loved Senator Specter,” said Angelo Cataldi, the host of the morning show at 94WIP. “He was, by far, the most honest, passionate and brilliant politician I ever met. In the early days of our show, he would call in to offer his thoughts after Eagles games. Then he visited the studio a few times. He was always totally informed on all sports topics—he talked Phillies with us, too—and I got to meet him outside the office every once in a while. He was beloved by friends and foes because he was his own man. None of this partisanship that has paralyzed the country now would have been possible with Senator Specter around. As a sports fan, he was fanatical—very outspoken and willing to use his power for the betterment of the games. He made no secret of his plan to investigate the NFL after Spygate. I never talked squash with him, but I did get to eat on a squash court one night when his son held a big birthday party for him. I have nothing but fond memories of my time with Senator Specter. Not a week goes by when I don’t say how much I miss him. Occasionally on Monday morning after Eagles games, I still imagine that he’s on one of our phone lines, ready to offer his opinion.”

Arlen Specter was famous as a traveling squash player. He played whenever he traveled, around the state, the country and the world. During his thirty years as senator, he traveled to upwards of a hundred countries, and every day on every trip he would play squash. “As soon as he landed, when we were driving into town from the airport,” remembered Joan Specter, who usually accompanied him overseas, “his first question was ‘do you have a game set up?’”

Arlen Specter was famous as a traveling squash player. He played whenever he traveled, around the state, the country and the world. During his thirty years as senator, he traveled to upwards of a hundred countries, and every day on every trip he would play squash. “As soon as he landed, when we were driving into town from the airport,” remembered Joan Specter, who usually accompanied him overseas, “his first question was ‘do you have a game set up?’”

John Fry, the president of Drexel, first met Arlen Specter when he was president of Franklin & Marshall. Specter came to campus twice after a student was shot off-campus in Lancaster. “He was unusually generous with his time,” Fry said. “It was amazing that a U.S. senator came not once but twice to our little college. I gave him a nice bag of F&M squash gear but he couldn’t accept it because of Senate gift rules. I would have loved to have seen him playing in full Diplomat colors. He loved talking squash. There was a twinkle in his eye when I told him about F&M squash reviving.”

Overseas trips were complicated. “We all sort of had a hand in organizing the matches in other countries,” Scott Hoeflich said. “I would work with people at the State Department. Conferences, meetings, fundraisers. I remember one time Bill Gates and I were talking outside a court, waiting for Arlen to finish his squash match.”

Hosni Mubarak was a target. The Egyptian leader was an avid squash player. After they first met in 1982, Specter approached him to play. At one point they had a match scheduled for the morning after a dinner—Specter had even brought him a Capitol Hill Squash Club tee-shirt and a Time-Life photographer was ready. But it was cancelled. “I suspect Mubarak felt that a squash court was too small a place for an Arab leader and a Jewish leader,” Shanin Specter said. “If they had played, my dad felt that they would have had a more productive relationship that would have benefited Egypt, Israel and the U.S. The squash court is a remarkably intimate place and you invariably walk off the court after a match better friends. He always regretted not playing with Mubarak.”

Because of the fact he played every day and his position as a leading political figure who traveled extensively, Arlen Specter probably played on more courts than any other amateur in squash history.

For a while, summers were tricky. The Specters spent their holidays at Harvey Cedars on Long Beach Island in New Jersey. The problem was that there was no squash nearby; to play, Specter had to drive off the island and battle traffic for at least an hour to get down to Atlantic City. Arlen’s son Shanin was law partners with Tom Kline who had a house just north of Harvey Cedars in Loveladies. One day in the early 1990s, Arlen said to Tom, “You know, Tom, there is no squash court on Long Beach Island.”

Kline had never played squash or walked onto a court. “I had never even held a racquet,” Kline said. “But I owned a tract of land and decided to build the court—with a sleeping loft, a shower, a kitchen. My view was that it would be good for the family and I put in a basketball hoop behind the back wall, so I could always just shoot hoops.” In June 1997 Kline opened the squash court. He then started playing. “Arlen had a goal of keeping me at his level,” he said. “He made me take a blood oath not to take any lessons. I picked up the game. There was a routine. He’d be down here, the dog days of August, with his kids and grandkids, and we always carved out time to play squash. I was Arlen’s speed and he liked to play with me so long as he was a tad better.”

Jules Zacher, a Racquet Club of Philadelphia player, also had a house nearby. “I’d get a call from Arlen’s scheduler,” Zacher said. “She’d arrange a match at 7am. I sometimes played with him in DC. Sometimes in Philadelphia on a winter weekend and he’d drive me home, in his car and drop me off at my place. A senator chauffeuring me around. But mostly at Long Beach. We’d talk after the match—fascinating conversations about politics, about the John Kennedy assassination. I can remember a couple of times when the phone would ring and it would be a staffer calling for the President and Specter would turn to me and say, ‘No way. I want to play squash.’ I always say that if Arlen Specter had become President, he would have taken the swimming pool out at the White House and put in a squash court.”

The summer routine included Specter showing up at the court in his squash clothes ready to go—their houses are a half-mile apart—and then stretching before play. He had an elaborate warm-up routine. He never talked before the match, only afterwards. There was no drinking after squash—just water and a cool down. He wouldn’t shower but would get back in the car and drive the half-mile home. More than once he did a remote broadcast feed into the Sunday talk shows in the space outside the Kline court. His staff put an American flag in the space and he’d get on Face the Nation or Meet the Press.

“He loved the court,” said Kline. “He took it seriously. It was a private court but he and I always wore whites. We probably played each other four or five hundred times. There was never a time he didn’t want to play. Squash, for him, was the best form of competition that involved strategy and acumen.”

In the 2000s Specter struggled on and off the court. He didn’t happily transition to softball. When hardball courts became scarce, he often pulled out his drawstring bag containing his squash balls and asked opponents to play with a hardball on the softball court. “Tracking down hardballs became a problem,” Hoeflich said, “and I found a guy in DC at a random tennis store that had a supply and I kept ordering from him. I’d keep balls in the glove box of the car, in desks.” Specter’s style was a problem too. He was a shotmaker. He would shoot from anywhere in the court. He had a serviceable reverse corner and a good cross-court nick, especially on his forehand. He had a great lob serve and was never afraid to hit the lob serve on a second serve. None of that translated well to softball. Often, when playing softball, he and his opponent would agree to two serves—in part so he could continue to send up high-lofting lob serves. He also compromised and sometimes used a bouncier softball, the red dot or blue dot.

He regarded his daily squash games as making a deposit in the health bank. “He had to make a lot of withdrawals,” Shanin Specter said. Arlen had a terrible run of health in his last years: he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2005; it came back in 2008; and then in 2012 he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. One of his three memoirs was titled Never Give In: Battling Cancer in the Senate. He famously played squash throughout the months of chemotherapy, even after he suffered a bad fall on court. In the last years, when he played squash at the Sporting Club at the Bellevue, partners remembered that after the match he would lay on a massage table and fall asleep. Sometimes he wouldn’t even play and just took the nap.

“The last time we played, it was just a couple of weeks before he died,” Kline said. “Unlike every other time, we didn’t finish the five games. I remember that day. He couldn’t play more than one game. ‘I’m pooped,’ he said, after the first game and walked off the court. That was when I knew.”

In October 2012 Arlen Specter died at the age of eighty-two.

In 2013 Tracey and Shanin Specter had dinner with Cara and John Fry. “We had a really good conversation,” said John Fry. “It isn’t clear now if I asked the Specters or if they offered, but we talked about Arlen and squash and the new national center. The next day I got an email that said they would make the gift and name the building after Arlen. It just made sense.”

“The name ‘Arlen Specter’ is on three buildings in the U.S.,” said Shanin Specter, pointing to the Arlen Specter Center for Public Service at Jefferson University in Philadelphia and the Arlen Specter Headquarters and Emergency Operations Center on the campus of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. “The other two reflect his interest in public service. A large part of him would be happiest to know that his name would be associated with squash. He loved squash. It was the best way we knew to memorialize his name. It was obvious. It will be at the intersection of sports and community.”

“The Arlen Specter US Squash Center,” Fry said, “joins a great sport with a great leader of a great country.”