Editor’s Note: While writing this article and as a result of what happened in the course of his match with twelve-year-old Milo Miller, Dan was diagnosed with both Early-Stage Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s (Lewy Body Syndrome). In his closing paragraphs, he discusses what this has meant for him and how continuing to play squash is one of the best things anyone can do to slow the progress of both diseases.

by Dan Hogan

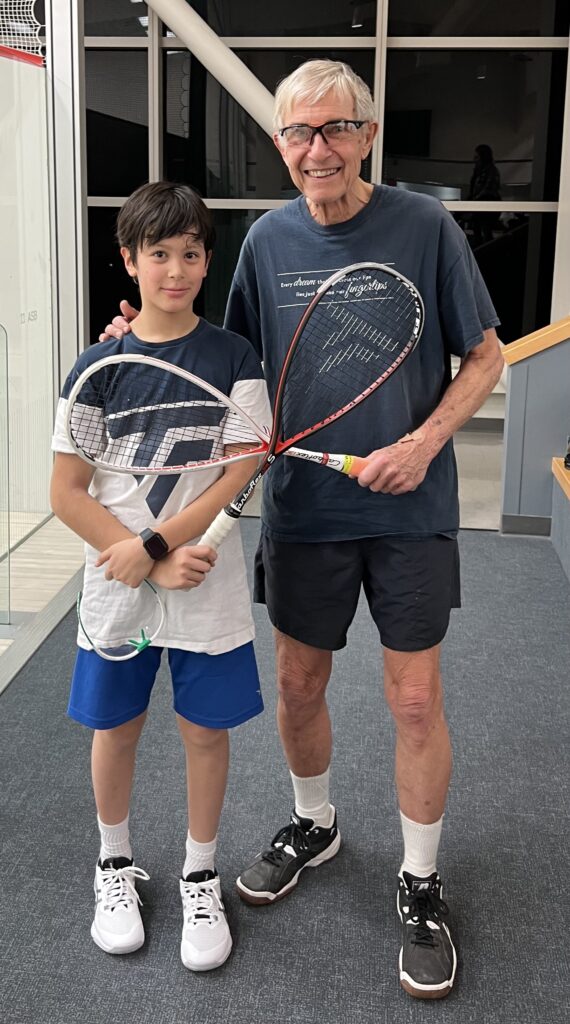

What do you have when you pit Milo Miller, a fast rising twelve-year-old, against a declining, soon-to-be eighty-year-old, Dan Hogan, in an early round of the 3.5 division of the 2023 Massachusetts Squash Championships? For one thing, a sixty-seven-year age gap. This possibly was the biggest age difference ever between two opponents in a U.S. Squash-sanctioned tournament.

Miller won deservedly and handily:11-6, 11-8, 11-4.

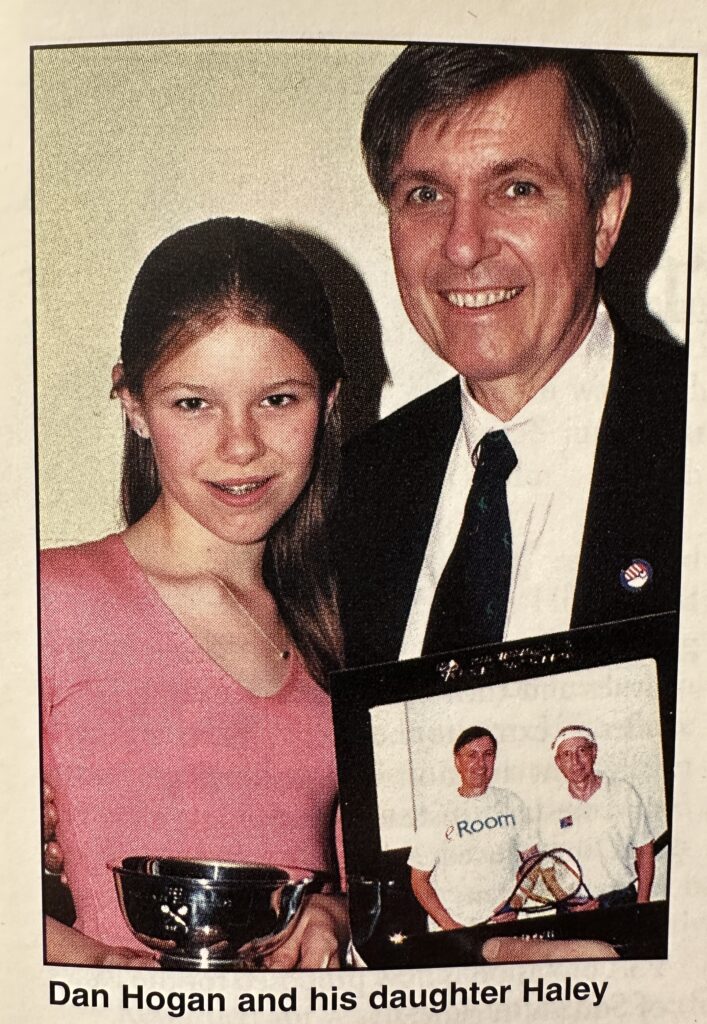

For me it was a second such unusual age-related match. The first occurred in 2000, when my twelve-year-old daughter Haley Hogan won the Massachusetts under-13 state championship, while I, at fifty-six, won the 55+. No one knows, of course, but it might very well have been the biggest age difference of any parent and child where each won their state championship in the same year.

The Mass state championships are played over a three-month period, during which juniors are likely to improve a lot. I certainly saw this with Miller. In April on finals night, his rating of 3.73 would have made him ineligible when he signed up for the 3.5 draw back in January. After beating me in the 3.5, Miller upset the one seed and made it to the finals where he finally lost. He also played in the 4.0, where he lost in the quarterfinals.

It wasn’t the first time I had played Miller. He and I are part of an informal group of two dozen men and women who play regularly at MIT. We have a weekly round robin on weekends, with pairs of players getting together at other times during the week. Eight of our MIT group made it to state championship finals night; I lost in the 70+ finals and finished third in the 75+ age group.

Growing up, my winter sport was ice hockey. At Exeter I captained the team and played on the varsity at Yale. In 1969 I arrived at Harvard Law School and learned that the Hemenway Gym, just a few yards from one of my classrooms, had a dozen squash courts. Having played tennis as a kid, I thought I’d give this new game a try. I loved it.

In my third year in 1972, I got to the finals of the D league state championship. I also played on the law school’s team in the Boston D league. The team was captained by Ed Cox, who a year earlier had married Tricia Nixon in the Rose Garden at the White House. Since Tricia’s dad was the U.S. President, this meant a built-in audience of Secret Service members at our matches.

After law school, I stayed in Boston and joined the Harvard Club. I improved and eventually graduated to the A league. I founded the “Harvard Has Beens,” which competed in the Boston A league. The Has Beens lasted about a decade, and we won the league title in 1981. We sometimes had an unfair advantage because we picked up Harvard varsity squash players who stayed in the area after graduation. At that time, I got involved in the governance of the Mass SRA as a board member, serving as secretary, vice president, league chair and tournament coordinator.

In the late 1990s, my youngest daughter, Haley, took an avid interest in the sport. I approached her school (Nashoba Brooks School) and the local pros at the Concord-Acton Squash Club (Paul & Wendy Ansdell) about starting a middle-school program. In short order, the Ansdells created a team that still exists two decades later, and Haley thrived, going on to play at Middlesex.

In the late 1990s, my youngest daughter, Haley, took an avid interest in the sport. I approached her school (Nashoba Brooks School) and the local pros at the Concord-Acton Squash Club (Paul & Wendy Ansdell) about starting a middle-school program. In short order, the Ansdells created a team that still exists two decades later, and Haley thrived, going on to play at Middlesex.

Until the mid-1990s, I remained a committed hardball player. I loved both the competition and the camaraderie. I looked up to the likes of Hall of Famers Lenny Bernheimer and Tom Poor, never taking a game off Lenny and managing just a single victory over Tom. Then I switched to softball. With the help of coaches like Thierry Lincou, I’ve had some good runs at the National Singles, losing in the finals of age-groups twice; I’ve won seven state age-group titles; and I’ve happily traveled to tournaments around the country. One of most memorable matches occurred in 2018. It was for third place in the National Singles men’s 70+. I was playing Ned Monaghan, a dear friend and longtime rival. I went up 2-0, lost the next two and in the fifth was down 9-6. I managed to run off four straight winners. At 10-9, match point, we had a long rally, and he hit a drop shot short on the left side. As a lefty, my natural response was a rail, but I could see he was ready for it. Instead, I contorted myself, and while starting to fall, hit a delicate cross court that died before he could get to it.

My hope is to play squash for the rest of my life, but over the decades, like so many other squash players, I’ve suffered a variety of sports injuries and health problems. In the finals of the National Singles 65+ in 2005, I tore the meniscus in the knee; I had surgery and then later a total knee replacement. In 2013 in the finals of the Mass state 65+, I ruptured not one but two of my hamstring muscles. In the same spot in the same tournament two years later, I injured my plantar fascia in my left foot, which took a year to heal.

Perhaps the biggest incident came in June 2017 when I suffered a sudden cardiac arrest on the tennis court. I threw up a practice serve and started to fall backwards, dizzy. I was unconscious before I hit the ground. My heart had stopped beating. Incredibly, on the next court was a friend who was a cardiac surgeon. He started CPR within a minute and traded off with my doubles partner, who was also a physician. At the twelve-minute mark, when the EMTs arrived, I still had no pulse. After four blasts of the defibrillator and seventeen minutes since onset, my heart started pumping again on its own. I finally regained consciousness in the ER at Mt. Auburn Hospital at about the forty-minute mark and miraculously, I had no brain damage.

At the 2021 National Singles, I wasn’t feeling well. I had trouble with my left hand—typing, holding things, including my racquet. I lost my balance a few times. Food didn’t taste right. When I got back to Boston, I learned that I had suffered a minor stroke that weekend.

This year, I started a new medical chapter. Recently I had been forgetting people’s names, forgetting where I put objects and having difficulty learning new songs on the guitar (I’m an old folkie from the ‘60s). My Mass state match with Milo Miller was a watershed moment. Leaving the court, Miller said, “Nice match, Mr. Hogan.” I responded, “What do you mean? We just finished the first game.” He replied, “No, Mr. Hogan, I won 3-0.” In disbelief, I asked again, and he confirmed the match was over. As we walked off the court, I queried his dad, who further corroborated the result. I still don’t have any memory of the match from early in the first game to the end of the third game, a gap that includes the two ninety-second intermissions when I apparently talked with both of my daughters and my partner.

Because of the amnesic incident with Miller, my neurologist ordered testing that led to a diagnosis of early-stage Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. I was shocked, then depressed and upset. Thankfully, having a strong purpose in my life quickly and totally turned me around. I’m now committed to being totally open about my conditions. My goal is to help others who are worried about having Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, or who already have these diagnoses, to get tested and treated, instead of ignoring, hiding or downplaying the symptoms they might be experiencing—an all-too-common reaction. While it would be easy to remain depressed, I also have optimism because it appears that I’ve been lucky to have been diagnosed early in the course of each disease. Optimism and positivity have been shown to be linked with positive outcomes. With both diseases, a significant possibility exists that my symptoms might naturally progress very slowly, and right now my symptoms do not appreciably affect my daily life and are not easily noticed by others.

The best action anyone can take for both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s is cardiovascular exercise. What better and more enjoyable way to do that than to continue playing squash? For nearly sixty years squash has been a crucial part of my life and I’m excited it will continue to be for many years to come.