By Eric Zillmer, Athletic Director, Pacifico Professor of Neuropsychology, Drexel University

We love competitive squash because it provides us with an accessible slice of life. We don’t only like to play squash; we also enjoy watching others while they play. Squash is like a complex, fun language. On the one hand, the structure of squash is reassuring. We keep score, there are lines and court dimensions, and then there is the tin. You hit it and the point it is over. The rules of squash are irrefutable; they reflect the order of the game.

But there is also ambiguity in squash. Mozart defined music as the silence between the notes, and so it is for squash. Between the structure of squash lies its delicious beauty. In 1912, the Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach famously said that he no longer “wanted to read only books. I want to read people.” A few years later he developed the Rorschach inkblot test, a set of ten ambiguous inkblots that test the human psyche. The Rorschach inkblots became psychology’s most controversial creation and also a cultural icon. In 2008 Barack Obama declared to the New York Times that he was, “like a Rorschach test. Even if people find me disappointing ultimately, they might gain something.” And in 2016, Jared Kushner mentioned to the Observer that his father-in-law Donald Trump was like a “Rorschach test … People see in him what they want to see.”

Squash involves many Rorschach-like arch-types: creativity, consciousness, discovery, and yes, winning and losing. The experience of the game is ultimately subjective and open to interpretation. For example, a match has only one numerical outcome, e.g., 13-11, 11-5, 11-2. Yet, players may interpret the outcome completely different based on who they are and what they experienced. Does this tell us something about the person? About the game of squash? Can squash players modify how they interpret their on-court performance?

Using the Rorschach test as a metaphor, the game of squash can be a catalyst for inquiry into our human psyche and help you perform better on the court. Below are three “Rorschach cards” related to the ambiguity within the game of squash.

Card II – Hermann Rorschach (1921)

“Two black dogs in love jumping up on their hind legs with their noses touching.”

Response by Amanda Sobhy, U.S. Professional Squash Player

“Two squash players high-fiving.”

Response by Simon Rösner, German Professional Squash Player

I. Attribution in Squash

If one conceptualizes the human brain as a very old, remodeled house, our ability to follow a ball, move and change directions can be understood as being hardwired as part of the old brain that was present from the very beginning of the nervous system’s evolution. The most recent addition of our brain house, however, is the penthouse, the frontal lobes. The frontal lobes organize behavior and are considered the conductor of our brain. Unfortunately, our frontal lobes are always turned on and therefore the owner of one’s brain often asks themselves: Why?

Performance sports psychology assists the athlete to think less, not more. So, our frontal lobes often get into our own way. But we can’t help ourselves; we must understand why we won or why we lost, even during a rally. In sports psychology we refer to this process as making an attribution about one’s own sports performance. Unfortunately, our insights into our own performance are ambiguous and often wrong, because they are biased. Research shows that we tend to overemphasize personal, internal characteristics and ignore situational, external factors in judging our own behaviors.

As a result, we often blame ourselves for a losing squash performance and believe that factors for success or failure never change. One always loses due to poor ability—“I played terribly”—or that one only wins due to luck. To change one’s perception of a performance, watch yourself on video or better yet, hire a coach to provide accurate feedback and consensus information on your game. As a squash player you are also your own psychologist. You need to challenge your own attributional thinking about your game to obtain a realistic and adaptive perspective of what you can and cannot control on the court.

II. Ambiguity and Creativity in Squash

Every shot in squash is a celebration of geometry and physics. Creating a winning shot on the court is one of the most satisfying parts of squash. Because squash is such a dynamic and fluid sport, the in-game situational sets are, like a Rorschach inkblot, complex and ambiguous. Should I attack? Should I shoot the ball? Should I continue to retrieve and stay in the point? This complexity is characterized by the movements of the players and in-game tactics of how to exactly play out a point. It makes up the ingredients for winning and losing and is most often related to creativity.

Research into sports-related creativity clearly suggests that the more an athlete can tolerate ambiguous sports-specific situations, the easier they can deal with them, engage in creative thinking and respond purposefully—which of course translates into winning.

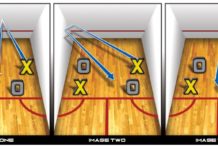

How can I play more creative squash? Well, one has to actually discuss situational awareness in practice on the court. The goal is creativity recognition and simulation. Other sports, like football and tennis, have made significant advances in analyzing big data regarding a player’s positional information and the development of specific formation patterns during play. Translated into squash, this means that the ability to accept ambiguity during a squash rally allows the competitor to stay in the moment and think of the point as a creative problem-solving situation. This cognitive paradigm of approaching play creatively also takes out the emotions of winning and losing by replacing it with a focus on innovation and creativity. To be a champion in sports, one has to be comfortable with the ambiguity of the game to allow for possible creative reactions and interactions. Just like a Rorschach test.

III. The Black Mamba

I was heartbroken over the loss of Kobe Bryant, Gianna Bryant, and the other seven individuals who tragically passed away in a helicopter crash this winter. I will never forget when Kobe Bryant played a high-school game at Drexel. We were mesmerized. I also bumped into him just last summer at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center during the U.S. Open. He carried himself with such self-confidence and dignity. A truly exceptional athlete and competitor. How did he do it?

As an athlete Kobe was like a Rorschach inkblot. Different people saw different things in him, some good, others bad. Kobe had to find a separate space from which he could operate successfully, without all of the negative distractions affecting him. To make it real, he gave this safe space a name, The Black Mamba, an alter-ego he created. The Black Mamba helped him organize his thoughts as a competitive athlete and feel free on the court. Whether Kobe figured this out himself, had a sport psychologist or was a student of Carl Jung, we will never know. But he was spot on. The Black Mamba mentality is a useful and a proven sport psychology tool. Kobe not only talked about it. He lived it. For Kobe, the Black Mamba handled business on the court.

A similar example—but for a team—is about my friend, basketball coach Jim Larranaga. In 2006 his team, George Mason, only had Connecticut between them and a historic first Final Four appearance. The alter ego created by the media for such teams as part of March Madness is Cinderella. But Larranaga convinced his players that the CAA on their jerseys stood for “Connecticut Assassin Association” instead of the Colonial Athletic Association. The team believed it and the rest is history.

Even squash club players can benefit from having an alternate on-court persona that allows them to compete aggressively and feel secure about themselves—a useful Rorschach metaphor.