by James Zug

Damien Mudge has an intentional relationship with velocity. For twenty years he played professional squash doubles across North America. The very first time he went on a doubles court, his boss and mentor at the University Club of New York, Gary Waite, wound up and cracked a ball hard. A quick demo. It was a backhand, but Waite had a good backhand and he blistered the ball. Mudge went into hysterics, laughing. This is real, he said to Waite. This is actually a game? I can crush a squash ball like that? I can do that? I’m in.

Mudge went on to create the modern game of doubles. He was big: six foot four, two hundred pounds, massive shoulders, strong legs. He hit the ball with a supersonic, super-turbo, fuel-injected surface-to-air missile speed. The waste heat scorched the court. His power needed timing, not just on the court but in the development of the game: he started doubles just when technology was forever changing the game (much lighter, stiffer racquets; high-tech strings; and newer, warmer courts) that shifted the old balance of speed and subtlety, of power and finesse. And he could do it for hours, punishing the ball, never tiring, applying continual incremental pressure like a tormenting torturer.

Yet Mudge was no dumb basher. He developed prestidigitational hands and was able to shoot and shoot well from all areas of the court. He built points. “Doubles is just looking for opportunity in the chaos,” said Gary Waite and Mudge was incredibly opportunistic. He was perhaps the greatest defensive player in history, retrieving beautifully, digging himself out of desperate situations, putting up cloud-licking lobs or twisting skid boasts or flicked, coruscating drops that not only gave him time to recover but actually put his opponent in trouble. Supremely hungry, he had a hair-trigger, ravenous alertness. He hunted balls down with ferocity, often ending up sprawled on the floor. His speed in and out of the corners of the court was unmatched.

He was complete. “All the greatest players in every racquet sport have three attributes,” said Morris Clothier, a legendary doubles player who played against Mudge. “They are athletic, they are competitive and they are intellectual. Only a tiny number have all three at a world-class level. Damien was one. You had to raise your game every time you played him.”

This past winter I met Mudge on the tenth floor of the University Club of New York. He was on the phone in the pro shop, a space that has no doors like most closet-like pro shops but seamlessly extends into a lounge area and two squash courts. (The University Club is like that, a century of mixing squash and a historic building means space is at a premium; there’s another court that you can only enter from the men’s locker room.) He was talking about property taxes.

He ambled over to the lounge after we finished. “Sorry about that,” he said. “On the phone with a tenant.” As we walked to the locker room, he told me that in the past six years he has owned nearly twenty rental properties around the country—Alabama, Wisconsin—and managing them has been an involving side hustle of deeds, foreclosures, mortgages and late payments. “It’s been mind-blowing to learn all these things,” he said. “This is not New York real estate. You are talking about real people. This has been my education in life, about people, about investing. It’s kind of cool to effectively go to school and make some money out of it. It’s been unbelievable, a mind-blowing experience. These guys ask me who I am—’where you from?’ and I’m like, ‘I am from New York.’”

Mudge is actually from South Australia. He was born in Port Augusta, a coastal village; lived for a couple of years in Marree, a tiny stop on the railway deep in the desert; and then started squash at age seven in a town called Port Pirie, a town with fifteen thousand people, the world’s largest iron smelter and one squash club with ten glass-backed, air-conditioned courts. He got good at squash. Every weekend, his parents would drive him and his older brother two and a half hours down to Adelaide, where they’d have a half-hour lesson and then drive two and a half hours back.

He always harbored a bit of the small-town kid in his personality. Behind the blustering Aussie façade, Mudge was never the most self-confident person in the room. He was shy. He didn’t speak fluidly; a tiny, fluttering stutter. He was almost a bully as a junior: he smashed racquets and intimidated opponents. In his first match in his first junior tournament, a young Ben Gould went on court to face Damien Mudge. “He sees me and he starts laughing,” Gould said. “I am scared straight. I’m about a fifth of his size and am thinking, ‘There’s no way this kid is in my age group.’ Mudge looks out at his buddies watching and says, ‘Who is eff is this little string bean?’ I was crushed. He destroyed me in about five minutes. He still calls me Stringer.”

Nearly twelve, Mudge and his family moved to Adelaide. He became one of the best juniors in the country, which in the early 1990s was perhaps the best hotbed for junior squash in the world. He joined the South Australian Sports Institute. He left before finishing high school and turned pro and joined the tour. He rose up to world No. 48. In 1997, after almost three years on tour, he contracted a virus while training in Malaysia and Singapore. He flew home and went straight from the airport to the hospital. Eventually he was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. He slept fifteen to eighteen hours a day. “I felt like a failure,” he said. “I hadn’t finished school. I had wanted to be a top ten player and now, I was twenty-one and washed up, no education, all my eggs in one basket. I had no money. I could barely walk.” In 1998 he sent a long heartfelt fax to Gary Waite. They had met on tour and in Toronto had trained and even roomed together briefly. “I had admired Waitey,” said Mudge, “how he trained, how he approached life. I thought he’d have some advice.”

A couple of weeks went by without a response. Then a one-sentence fax came spitting out of the machine: Call me, I’ve got a job for you.

A year earlier, Waite had become the head pro at the University Club of New York. When Mudge faxed, the club needed an assistant pro. Rob Coakley, the chair of squash committee, gave Waite three ironclad ground rules for the search: the assistant must be someone who is an experienced teacher and coach, someone who doesn’t need a visa and someone who speaks English. Mudge violated two and a half of the guidelines: he had never given a lesson before, he had no papers and he spoke with a thick South Australian accent.

Mudge arrived in New York with $500—or rather $420, as he got ripped off on the taxi ride from JFK Airport to Manhattan. In the beginning he napped a lot, sleeping on couches and chairs. “He would fall asleep all the time,” Waite said. “He’s big. I’m thinking, ‘How can I pick him up and carry him to the couch?’ I’d come into the pro shop and he’d be asleep, drooling on the booking sheet.”

Mudge jumped right into life on the tenth floor of the University Club. “He was clearly a disaster on paper,” said Rob Coakley. “He fit none of our criteria. But immediately we saw something in the guy that we loved. The force of his personality came through right away. He became a family member to literally dozens of people at the club and in New York. A tremendous friend. And on court, he had such tenacity. Like Michael Jordan or Tom Brady, he played with a chip on his shoulder. He wanted to win.”

On court, singles was out of the question, but doubles, once he got over the hilarity of the speeding ball, was something Mudge could do. First he partnered with Kenton Jernigan, a member at the University Club. Jernigan, a Hall of Famer, was at the tail-end of his career, post-hip surgery. “Damien was still recovering from the chronic fatigue,” Jernigan said. “Sometimes he wasn’t feeling good in matches, not moving well. He was still learning the game, positioning. He was so freaking fast that he could cover the balls up front even though he was standing too far back. In the evenings, we’d play sides, practicing alone, heat the ball up. He clearly had the tools.” They had some bad losses but also some good ones, including a two and a half hour tussle with Gary Waite & Mark Talbott, the dominant team that year.

After about a year, Jernigan moved to London, and Mudge switched partners to Gary Waite. “Mudgie was a bit raw,” Waite said. “He was deceptive. He was a like a guided missile out there, with a lot of ability but he came across like a carefree Aussie who had checked out and was ready to go surfing. People weren’t ready for him. The first time we played together, it was in Chicago and Mudgie just pounded a ball down the rail. Dean Brown was on the right wall and he lifted his racquet and just stood there. He had lost sight of the ball. It went right by him.”

The first time I saw Mudge play in a tournament was at the 1999 Johnson at the Heights Casino. I wrote in my notepad that Mudge and Waite had won the previous weekend in Chicago and that Mudge was “huge” and an “awesome talent” and “hitting the hell out of the ball.” At one point, after a massive Mudge blast that sent the ball to the back wall before it seemingly left his racquet, Waite turned to him and said, “Jesus, you brute.”

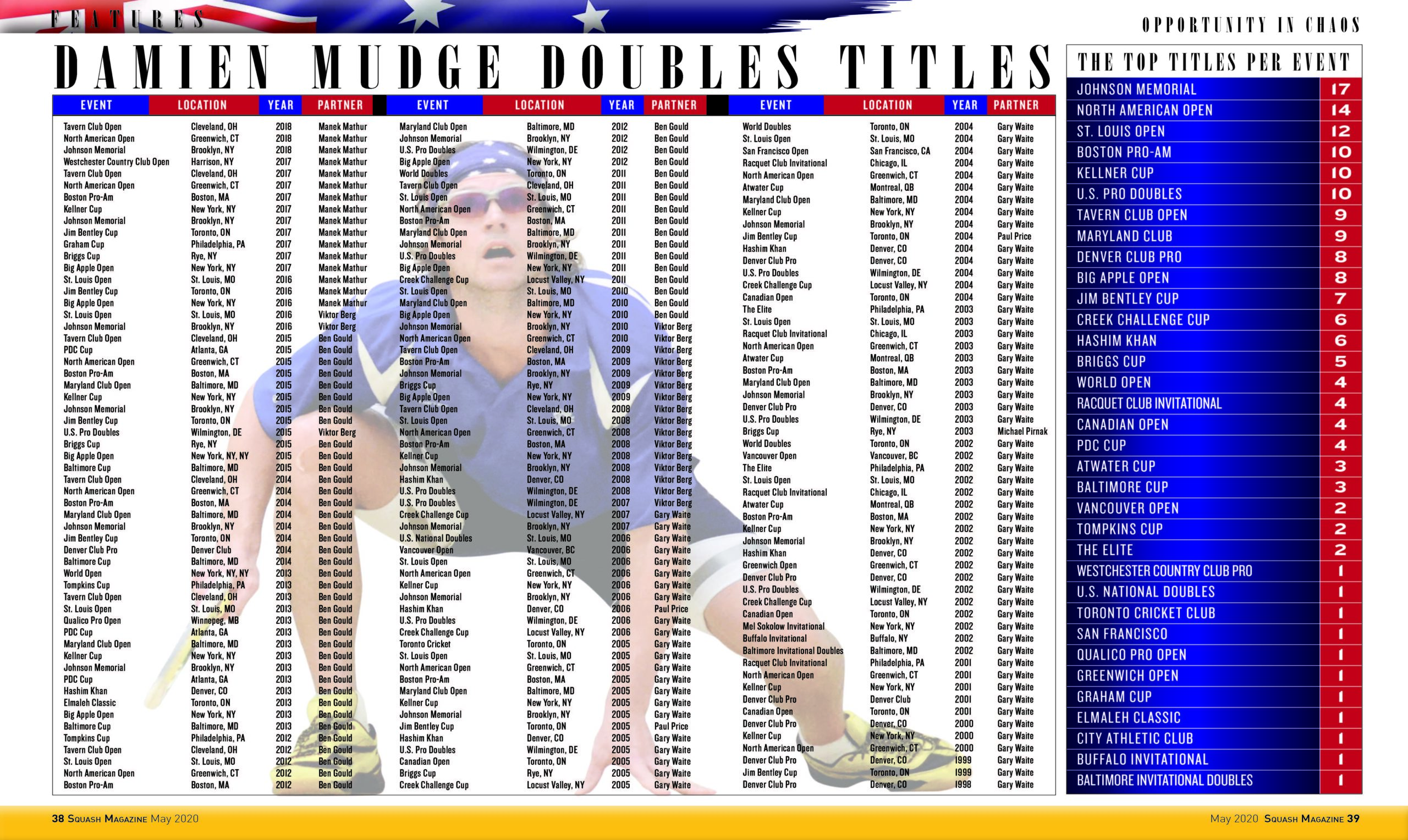

Mudge’s health slowly improved. Once a month he’d go for runs along a boardwalk on the New Jersey shore and eventually, the runs left him feeling good rather than depleted. He slowly got the hang of doubles. In the early aughts, Waite & Mudge dominated pro doubles. They completed three undefeated seasons and captured seventy-five tournaments, the most of any partnership in pro doubles history. “We were cannoning the ball,” Mudge said. “It was a bloodbath.” In those years, Mudge came to epitomize pro doubles: youthful, resurgent, exciting. In 2000 the tour separated from the pro singles tour. The number of events and prize money doubled and then tripled. Clubs held six-figure tournaments. Top singles players migrated to the tour and in a few years two dozen countries could boast a pro doubles player. The World Doubles really was.

Women’s pro doubles started. More courts appeared, more amateurs, more juniors, more college players. Mudge was the consecrated magus. Everyone called him Mudgie. He was the best player. He worked hard on court but didn’t take it too seriously. Once, before walking onto the court for the finals of the 2001 North American Open, he quietly told me that he was “going to give it a bit of a tap.” He hit balls off the back wall between his legs. He hit no-look cross-court volley nicks. He smiled after stunning shots. He would show up to the club ten minutes before his match, take a shower and then be ready to go; after a match, a beer would be glued to his hand. Eventually he was the senior statesman—for a long while at the end of his career, he was the only player on tour left from the 1990s.

After six years of Waite & Mudge, boredom crept in, and Mudge wanted a new challenge: playing the left wall. “I wanted to redefine who I was as a pro,” Mudge said. “I wanted to open up my mind and be more patient, more thoughtful and more strategic. I wanted to improve myself.” The well-chewed wisdom of squash doubles was that the right-waller bashed and created openings and the left-waller shot. “Damien always hoped to keep the integrity of his game there,” Waite said. “He wasn’t a basher. He needed to prove that he could play both walls, that he had good shot-making technique.”

Mudge partnered with Viktor Berg. They won their first tournament, the U.S. Pro, in Wilmington. “In a way, that was my greatest win,” Mudge said. “I was most excited about that. I really didn’t think I’d win at all on the left wall. I thought I’d never win an event again.” Mudge & Berg shot to No. 1 in the rankings. “I couldn’t believe how my game instantly improved,” Berg said. “His level of expectations made me rise to the occasion.” But they weren’t untouchable. They developed an epic rivalry with Paul Price & Ben Gould. Mudge & Berg wore white; Price & Gould wore black. For three years, one of those two teams captured every full-ranking pro event, with each team winning seventeen and Price & Gould boasting a 9-8 head-to-head advantage in their seventeen finals. One memorable final was at the Kellner Cup in New York, when Mudge & Berg emerging as victors after nearly three hours; another was the Johnson at the Heights Casino, where Berg rolled his ankle up 12-7 in the fifth and then got drilled in the same ankle (“It was basically numb,” Berg said). As the match reached its denouement, Berg smacked two winners while hobbling around on one leg, and then after a mad scramble Mudge finished it off with an inside-outside forehand reverse corner.

In 2010 Mudge and Gould left their partners and joined together. “It’s important to me to be good friends with my partners,” Mudge said. “It’s not what you are doing but how you are doing it. I’m process-driven. There is an intimacy and depth to a relationship with a doubles partner and I’ve always had that, all the way through.” Gould and Mudge were good friends from childhood—after that first match in juniors—and had eerily similar trajectories (reaching top fifty in the world, battling chronic fatigue and working at private clubs in Midtown Manhattan). Even throughout the Mudge & Berg v. Price & Gould years, they remained friends. “With the rivalry, there was a lot of angst on court,” Gould said. “We were fiercely competitive. But off court, we never let anything interfere with our friendship. We’d pick up the phone and talk. Mudgie is an old soul.”

Mudge & Gould went undefeated that first season and over five seasons compiled a 189-7 record while capturing fifty-five titles. “A lot of people thought we were making a dumb decision to play together,” Gould said. “They said we were both going to be bashers and couldn’t finish the point well.” They wore Australian-flag bandannas—Mudge reveling in his roots after partnering with an American and two Canadians.

In 2015 Gould moved to Boulder and retired. Mudge almost retired too, but he decided to approach one particular player first. “He called me and said, ‘Do you want to grab a coffee?’” said Manek Mathur. “I said, ‘You don’t drink coffee. What’s up?’” With Mudge back on the right wall for the first time in a decade, the combo lost in their first tournament together, in Baltimore in 2016. Then Mathur & Mudge went on a tear, not losing again for the rest of that season and the next, sixteen tournaments and fifty-four straight matches. For Mudge it was a lovely swansong, no pressure, just the joy of playing. “I asked him the first time we played together about strategy, tactics, what the plan was,” Mathur said, “and he said to me, ‘No, mate, just go out there and move the ball around.’”

With Mathur, Mudge rounded out his remarkable career. He captured the last two of his seventeen straight Johnson titles. As the oldest and most prestigious annual pro doubles event in the world, the Johnson is the pinnacle of the game, and Mudge set a record in Brooklyn that almost certainly will never be broken.

Mudge is a physical oddity. He is magnetic. When you go out with him to a bar, strange things happen. A primal aura surrounds him. People stare at him. Women are drawn to him and sometimes flock to his side like a 1950s Hollywood movie. Men, especially similar-sized men, are provoked, with no reason, to get in a fight with Mudge. He is good at diffusing these situations. Gary Waite remembered an evening at a biker bar in the old Meatpacking District in New York: “I was at the bar and couldn’t get a drink,” Waite said. “Then four huge bikers moved aside, like the Red Sea parting: Mudgie was walking to the bar.”

Mudge delights in telling the tale of his failed modeling career at the Ford modeling agency (the punchline: he was told he was too tall, too broad-shouldered and his face too round) and how, after he was selected, he turned down appearing as the bachelor on The Bachelor (show No. 8).

At the same time, his body has been remarkably fragile. He endured a couple of lifetimes of injuries. He had eight knee surgeries. Three came from squash, the rest from life. One resulted from after he tore his meniscus doing the pigeon pose in yoga; another after hitting golf balls on a driving range; and a third after getting a massage. He shattered his left wrist in a roller-blading accident on 55th and Fifth Avenue. He tore the ligaments in his playing wrist. Shoulders and feet. He suffered multiple concussions on court, getting hit with a racquet, banging into an opponent’s hip.

Once he was training with Carl Baglio, an assistant pro at the University Club. He was teaching Baglio how to be aggressive on balls down the middle of the court. A ball came down the middle; Mudge ducked; Baglio swung, missed the ball and broke his racquet on the back of Mudge’s head. He didn’t get a concussion but the force of the impact dislodged the vitreous in the back of his eyes. All of a sudden he had a lot of black floaters. When he was on a squash court, with fluorescent light and the white walls, it was too distracting. He experimented with sunglasses and different types of color tints to soften the contrast between the floaters and the white background. Eventually, he used a red-tinted pair of sunglasses. What appeared to the novice observer that Mudge was a too-cool-for-school pop-star wearing sunglasses inside was actually another medical issue.

In the second game of the finals of the season-closing 2018 Tavern Club Invitational in Cleveland, Mudge tore his right knee again. He couldn’t lunge. Mathur & Mudge won the match in four and preserved their undefeated season.

He never played another match. A year and a half later, at age forty-three, he officially retired. If one can be certain of anything in squash, it is that we shall not look upon the likes of Damien Mudge again.