By Richard Millman

We are still very early in the exploration of squash as a sport. We have only been playing since the 1850s. When you compare a century and a half to the long history of mathematics, astronomy, law, medicine or physics, you can see that we are still fumbling around trying to identify and solidify concepts. This is something I hope to do before I give up the ghost. I am keenly aware it is necessary because there is really something there in squash and studying it empirically will yield valuable knowledge for humanity beyond the scope of our wonderful game.

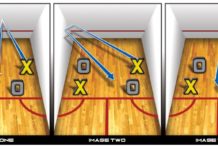

One of the concepts that we don’t have nailed down is the concept of where to position yourself to maximize your ability to defend the court.

The calculation of strategic position in squash are akin to a goalie in soccer or ice hockey or lacrosse, except a squash player has to defend a three-dimensional target instead of a two-dimensional target like a goal. The key for any goalkeeper is the same however, no matter what sport we are talking about. A goalie tries to narrow down the angles of possibility for any opponent. We are a little better off than the soccer, hockey or lacrosse player because the opponent can’t pass the ball to a teammate to change the angle, so we have one constant that we can use: the location from where the ball is coming.

To be a world class defender in squash, you need to be able to recognize all the available choices that the opponent has from the location at which they are playing the ball. You need to feel the distances of the physical court around you and to recognize the place to stand that bisects both the time and distances available to your opponent. That’s some pretty heavy math and not something you can consciously calculate. By doing a lot of pressure drills with someone who knows how to feed pressure at the very limit of your capacity and to punish you when you leave a space open, you can learn the geometry of strategic defense.

One of the great defenders in my time was Ramy Ashour. Many of us were astounded at his ball control, but for me the frequency with which he narrowed down his opponents’ angles of possibility and intercepted balls so early was amazing. He managed to turn defensive positions into overtly offensive situations where opponents who had ownership of the ball were cowed into playing defensively for fear of the early intercept counter attack, even though they were in charge of the rally at that moment. That is math genius.

Homework: Ask a partner or coach to feed you balls all over the court but you are only able to return the ball to one corner. Try seventy-five shots if you are a fairly fit 3.5-5.0 player, a hundred shots if you are 5.0 and above. Do multiple sets of the drill, resting between each. Try to get to the point that you become comfortable and familiar with the feel of where to stand. Don’t think about the T or the T position or any words relating to a fixed point on the court. Develop a feel for the court around you and learn to narrow down the angles of possibility. Gradually learn to turn defensive strategic positions into positive offensive situations.