By James Zug

555: The Untold Story Behind Squash’s Invincible Champion and Sport’s Greatest Unbeaten Run

by Rod Gilmour and Alan Thatcher

Worthing, England: Pitch Publishing, 2016

It is hard to recall now, a quarter of a century later, just what a big deal Jahangir Khan was.

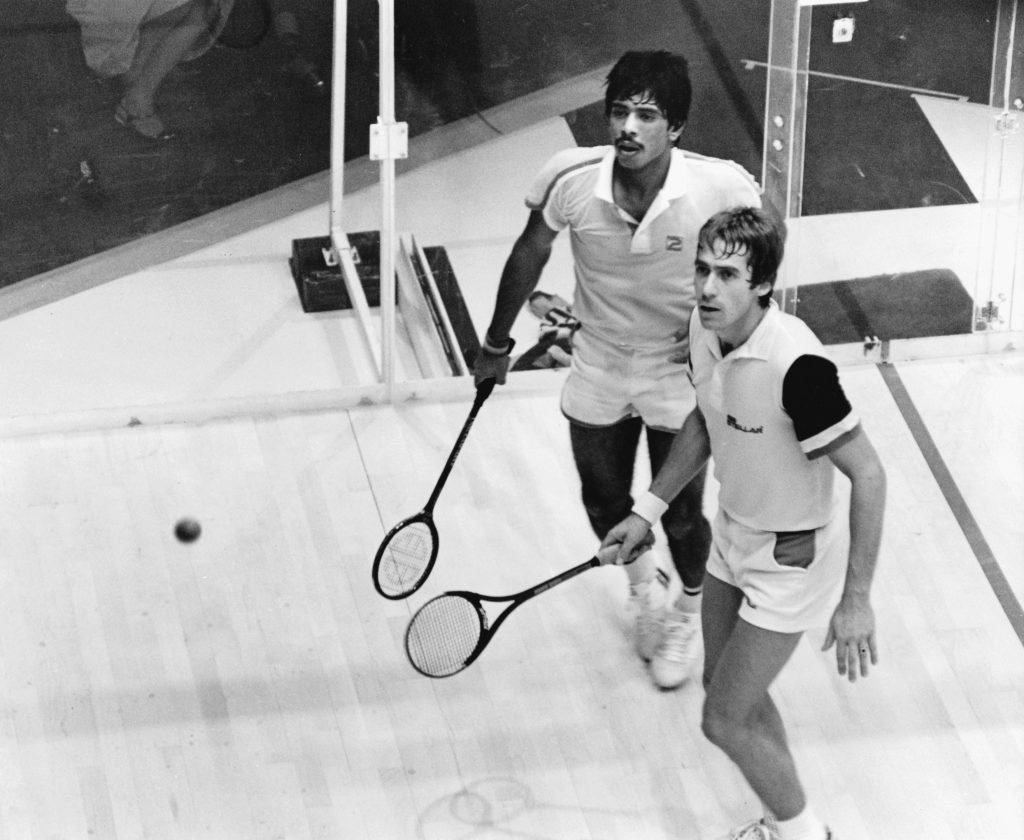

He was consistently dominant like no other player in history. Tournament after tournament, month after month, year after year he crushed his opponents. He triple-bageled them (he won the finals of one major tournament 9-0, 9-0, 9-0). He crushed them. He chopped them. In the 1983 World Championships, he lost a total of thirty-nine points over six matches. Some guys stepped up, fought hard in a match and then were never the same again. And Jahangir did this mostly while still a teenager; he is still the youngest player to have won the World Championship or the British Open.

His timing was impeccable. His appearance coincided with the rise of professional squash: the invention of the portable court and the graphite racquet, the plunge into big corporate squash. It was boom-time for the man who lowered the boom like no other. Despite his quiet demeanor and his monastic lifestyle, he became a global icon. It has been said that he was the first—and perhaps still the only—millionaire in the game.

His timing was impeccable. His appearance coincided with the rise of professional squash: the invention of the portable court and the graphite racquet, the plunge into big corporate squash. It was boom-time for the man who lowered the boom like no other. Despite his quiet demeanor and his monastic lifestyle, he became a global icon. It has been said that he was the first—and perhaps still the only—millionaire in the game.

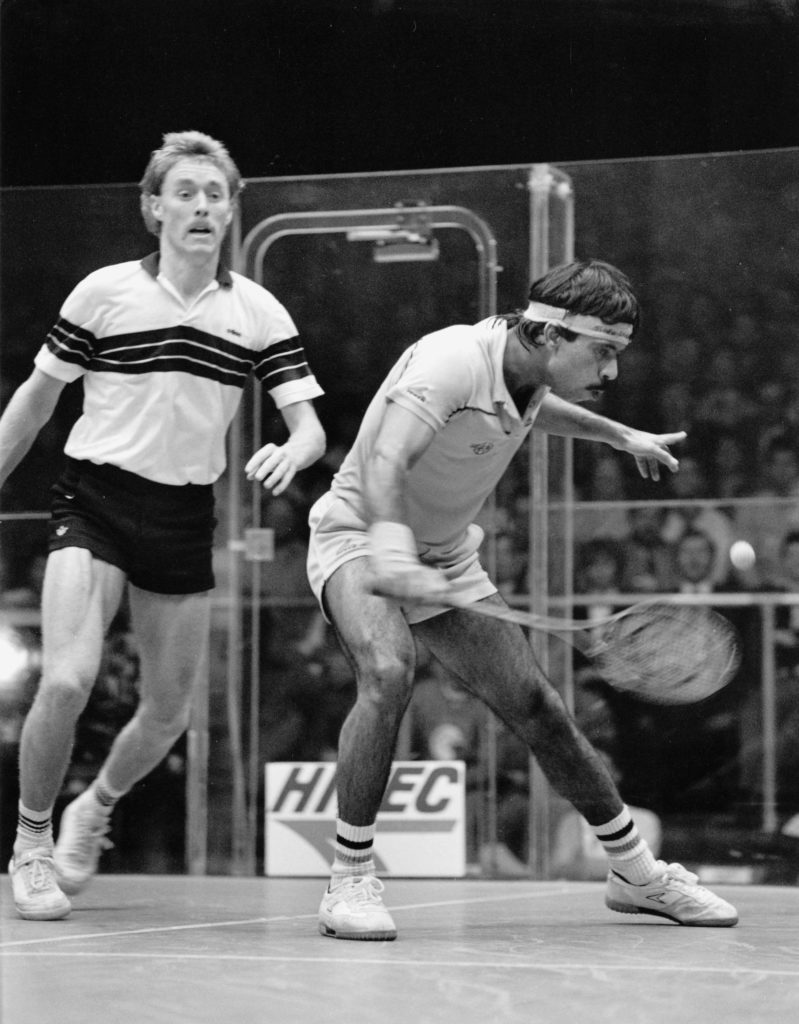

There is no squash Grand Slam, no four majors to add up like in golf and tennis. We are left with only a few memorable numbers: sixteen (the number of consecutive British Opens Heather McKay captured); 109 (the number of successive months Nicol David was world No. 1) and above all 555, the number of matches Jahangir Khan supposedly won in a row, from losing in the finals of the 1981 British Open to losing in the finals of the World Championships in 1986, the inhumanly long stretch of five years, seven months and one day.

Triple Five is, alas, an illusionary number. Unfortunately, the ISPA, the men’s pro softball tour founded in 1973, didn’t keep accurate records until Howard Harding came into the game in the early 1990s (you can deep-dive into all kinds of pro squash data at Harding’s squashinfo.com). Five hundred and fifty-five straight wins means more than twenty tournaments a year and there weren’t nearly that many in the early Eighties. Khan’s rather feeble defense of the number, according to Gilmour & Thatcher, is that if you add in exhibitions and challenge matches, you’d get to 555. Or more. Maybe 700, he said, noting that he once played in twenty-nine exhibitions one busy month in Germany. Exhibitions?

The story of Jahangir Khan isn’t really “untold.” Although Gilmour & Thatcher call Dicky Rutnagur the doyen of the squash press of that era and slide in a supererogatory but funny tale about him, they oddly don’t list Rutnagur’s 1997 book Khans Unlimited in their bibliography. But Rutnagur’s book is well-known (a new paperback edition was published earlier this year and was for sale, with Jahangir’s autograph, at the 2016 British Open) and more than a fourth of it is devoted to Jahangir.

Nonetheless, Gilmour & Thatcher flesh out the story in a congenial manner. One of the many benefits of this engaging, entertaining and essential book is Gilmour & Thatcher’s investigation of the provenance of the 555 number. But they did much, much more. They researched in the British Library and interviewed many people who played against Jahangir, worked with him or observed him, as well as Jahangir himself. They ferret out Graham Dixon, an English referee who in April 1976 spent a month in Pakistan with Roshan when Jahangir was twelve and Brian Townsend, a fitness guru in Toronto who tested Jahangir’s renowned physical capacities. They elicit fascinating stories from everyone from Maqsood Ahmed to Gawain Briars, Adrian Davies to Chris Dittmar and Geoff Hunt to Hiddy Jahan. A key interview was with Rahmat Khan, Jahangir’s cousin who served as his coach, trainer, manager and consigliere.

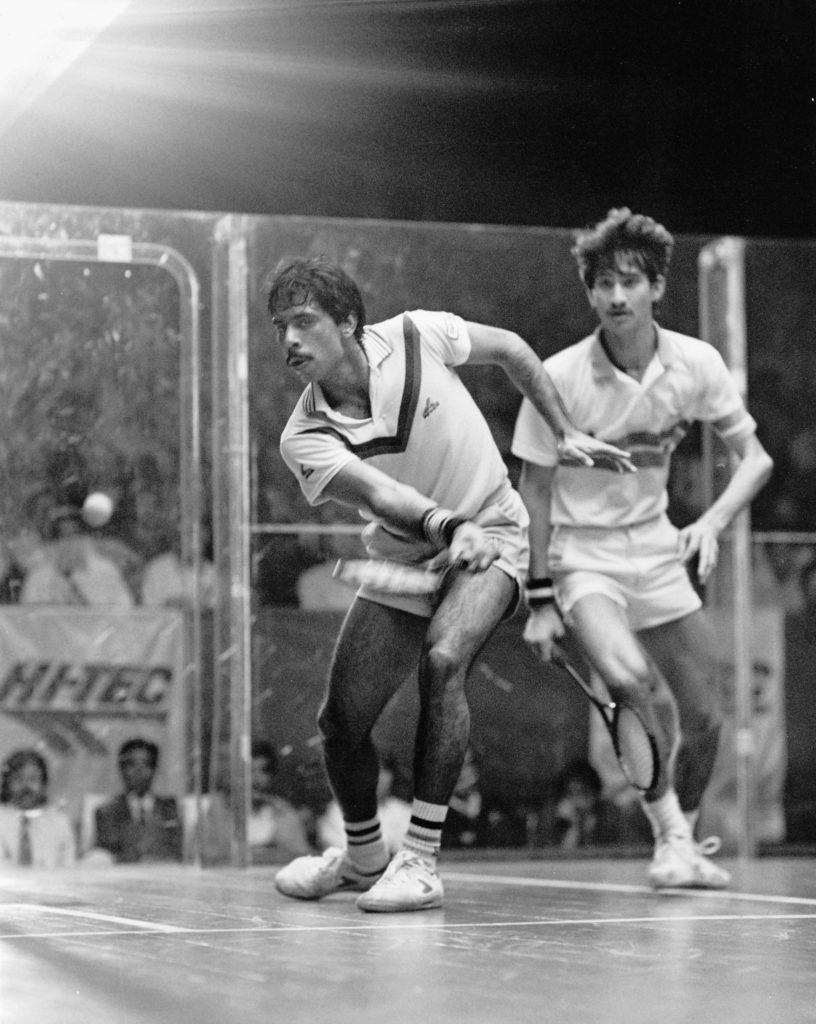

They deconstruct celebrated matches at the start of the streak—Hunt beating Jahangir in the 1981 British Open final—and at the end of the streak—Ross Norman toppling Jahangir in the 1986 World Open final—as well as perhaps the most astounding of all, the 1983 Chichester Festival final, where Jahangir and Gamal Awad endured a four-game, two hour and forty-six minute marathon. Thatcher was there that night and delightfully reports some of the insane details, like the fact that when the match was twenty-two minutes old, the score was still 2-1.

they played.

They mention tidbits I didn’t know: that because of hearing issues Jahangir didn’t start to talk until he was eight years old; or that in 1985 Jahangir signed a contract to wear eye goggles playing softball—a sight I’ve never seen.

Moreover, they happily divert themselves well beyond Jahangir’s narrow biography to describe the wild west that was the squash scene in the 1980s. 555 is as much a celebration of a lost era as it is of Jahangir Khan. They devote two full pages to stories of Kevin Shawcross, a notorious legend of late-night fandangos. One page goes to a Danny Lee tale of getting from Bristol to Madrid via car, ferry, truck and plane: an all-time top-tenner in the Annals of Best Squash Travel Stories. Another page is given over to Mohibullah Khan, Jr. and his arrest and jailing for nine years for smuggling three kilos of heroin into England. And another to Lisa Opie’s explosion at the end of a British Open final: racquet flying out of court, two middle fingers for the referee. And they regurgitate one of the great quotes from Rex Bellamy, the former Times [of London] squash correspondent, about viewing squash on the new glass court for the first time: it was “like watching a couple of cockroaches copulating on a distant beach.”

A couple of quibbles. They get wrong the relationship of Roshan Khan—Jahangir’s father—to the great patriarch Hashim Khan: they were not first cousins once removed but rather Roshan was the son of the sister of a man (Safirullah Khan) who married Hashim’s sister. They misstep when talking about the International Olympic Committee leadership, saying Thomas Bach had the penchant for Belgium rugby, when it was Jacques Rogge. And it is always Edwin Moses, not Ed when talking about the great hurdler (Ed Moses was a four-time Olympic swimmer).

Although they list my 2003 Squash: A History of the Game in the bibliography, they evidently didn’t read it carefully. They state that squash was invented in the Fleet prison, an old canard that I definitively proved false. They describe the double boast imprecisely and say that Mark Talbott was from Florida (rather than Ohio).

Most of all, they misrepresent nature of Jahangir’s invasion of North America, spending most of their attention on an inconsequential three-day exhibition at the start of his four-year tour.

Jahangir played in fifteen events in the U.S. and Canada. He lost in two. Mario Sanchez throttled him 3-0 in the semis of the 1984 Canadian Professionals and six months later Mark Talbott beat him 18-16 in the fifth in the finals of the Boston Open.

Because of those losses, there is no Triple Five streak. In the end, this book points to a fundamental misconception about hardball squash. It wasn’t some freak of nature unrelated to the rest of the world. It was just a high-powered, exciting variant, a different “code” as Gilmour & Thatcher call it. Jahangir took the hardball matches seriously. He played before a thousand people at Town Hall in New York. He earned the biggest paychecks of his career. He garnered most of his sponsorships. Yes, the balls were slightly different—he played with both balls in North America. And yes, the width of the court varied: he played on a eighteen and a half foot wide court, the twenty-foot portable tour court and twenty-one foot courts. In its decade-long run, for example, the invitational Mennen Cup in Toronto—Jahangir’s largest annual payday—was played on all three sizes of courts and with both balls.

Looking back, with more than two decades of hindsight, we see that hardball and softball imperfectly but nearly correlate to variations in tennis, between Roland Garros, Wimbledon and the U.S. Open: different surfaces and different balls. (Even men and women use different tennis balls today: across the pro tours, the women use a regular felt ball and the men an extra-duty felt ball.) Or perhaps to golf, with variations in courses in the Grand Slams. Do Federer’s wins at Wimbledon count differently than his wins at Flushing Meadows? Do Nicklaus’ wins at the British Open count differently than his wins at the Masters. Of course they don’t. Jahangir’s two losses in North America negate any unbeaten run.

Gilmour & Thatcher quote from an email I sent them earlier this year in response to a query, where I quickly laid out the argument above. But they don’t respond or rebut it. Why? Because then there is no streak. And that is a shame because Jahangir’s achievements, regardless, certainly back up their claim that he is probably the greatest sportsperson of all time, and the book is valuable and insightful, no matter of what number appears on the cover.