By James Zug

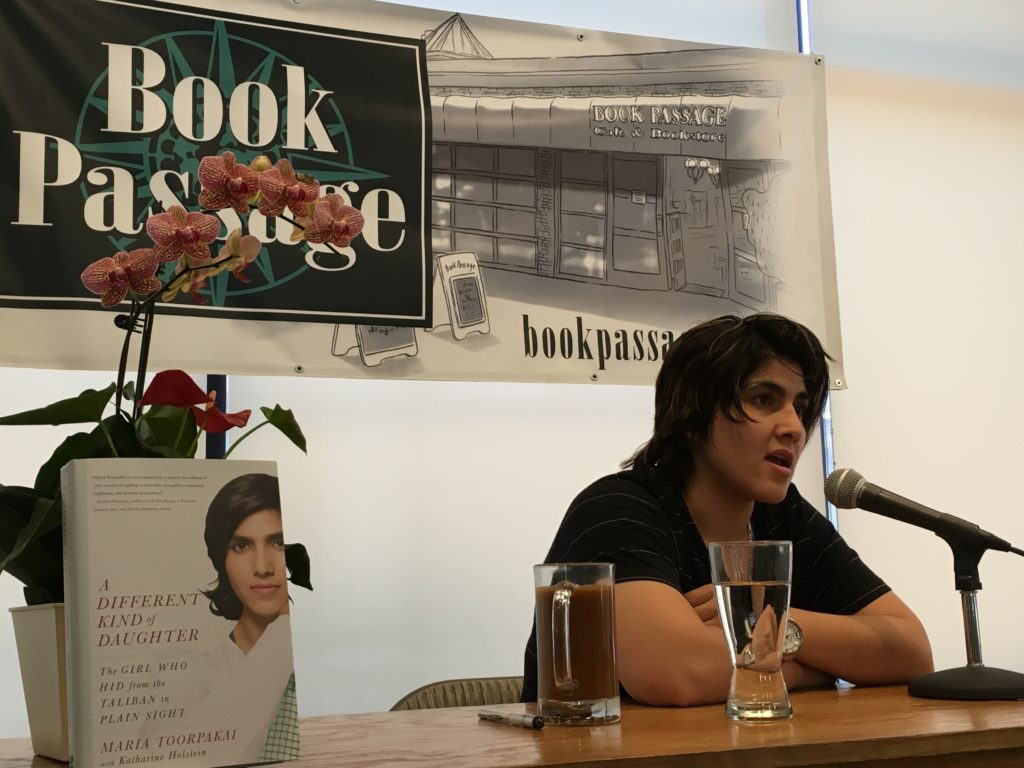

A Different Kind of Daughter: The Girl Who Hid from the Taliban in Plain Sight

By Maria Toorpakai with Katharine Holstein

(Twelve, 2016)

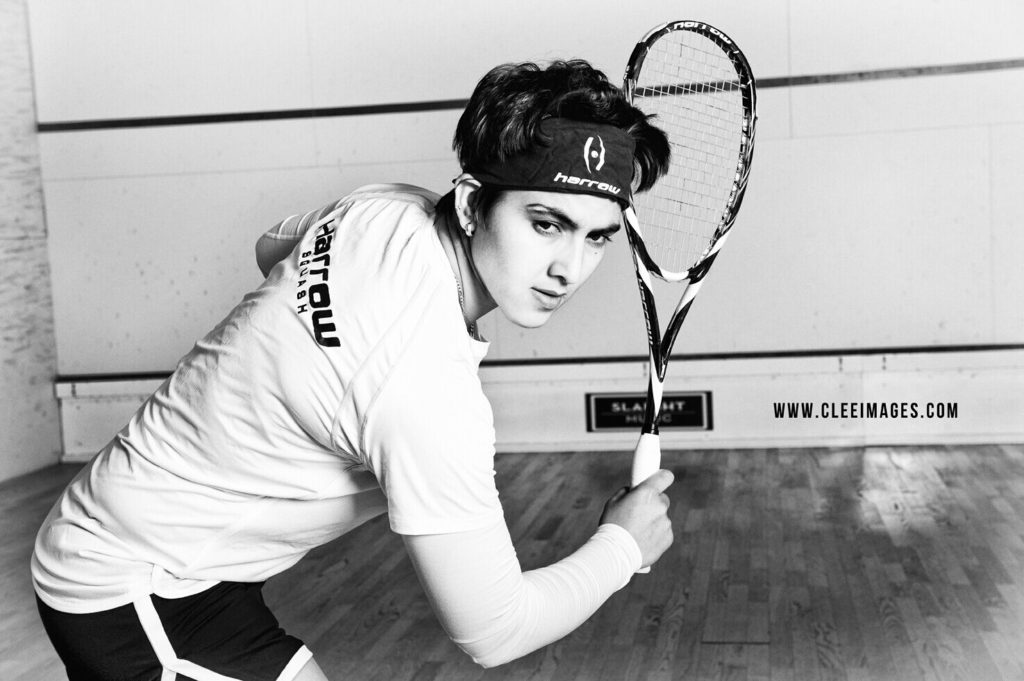

Within the squash world, it was well-known that Maria Toorpakai had a special story.

She had been a promising junior, the first woman to come out of the great squash nation of Pakistan (Carla Khan, the granddaughter of Azam Khan, reached world No. 21 and beat Nicol David in the 2004 Irish Open, but she was born and raised in England). Playing in international events since 2004, Toorpakai regularly appeared in junior and adult tournaments around Asia. She also entered four British Junior Opens. She won the Pakistan nationals in 2007, winning her final two matches in the tournament in a total of thirty minutes.

In the 2009 World Juniors in Chennai, she did very well. She topped Kanzy El Defrawy in the quarters 11-8 in the fifth. In the semis she went down to the eventual winner, thirteen-year-old Nour El Sherbini in twenty minutes.

In February 2011 I came into Vicmead Hunt Club for the first round of the Delaware Open and met Toorpakai. She was painfully shy, nervous, her English not that good, and she briefly told me that this was her first tournament ever in the U.S. She lost to Sina Wall in three hard-fought games and disappeared.

At the time, I naively thought it was just another example of the globe-trotting nature of squash pros, that Toorpakai was finally on the road—although I wondered what her backstory was and why it had taken so long for her to appear on the world scene, nearly two years after Chennai. A few months later we heard she was basing herself in Toronto, training with Jonathon Power.

As we learn in A Different Kind of Daughter, that tournament in Delaware was a pivotal moment in the young woman’s life. She was fleeing the Taliban.

A few months after Toorpakai arrived in Toronto, Power went to a benefit dinner in Los Angeles. He sat next to Cassandra Sanford. A founder of Blackacre Entertainment, a production company, Sanford was taken by the story of this new protégé in Power’s stable. One thing led to another, and for the past four years a team led by Sanford and director Erin Heidenreich has been filming a feature-length documentary about Toorpakai. (One of Heidenreich’s docs, the 2014 The Other Shore, is about another squash player with a great story, Diana Nyad and her attempt to swim from Cuba to Florida.) They made multiple trips to film in Pakistan. It has a working title of The War to Be Her, received the 2015 AOL Charitable Foundation Award from the Tribeca Film Institute and is premiering at the Toronto Film Festival in September.

Then a book deal was brokered and this spring her memoir appeared. The blitz of media attention for the book is unprecedented in the squash world. Toorpakai has spoken at conferences and forums, on national television and radio. Articles on her, interviews with her, excerpts from her book, reviews of the book, requests for her to speak—it is a flurry of attention in America that we’ve never seen for a squash player.

A Different Kind of Daughter was written by Katharine Holstein, a screenwriter in Toronto. Although she never went to Pakistan to visit where Toorpakai was born and raised, Holstein deftly captures the atmosphere of Toorpakai’s childhood. At times she injects too much poetry into the story: a dress is left on the floor “like a bit of sunset left melting to a puddle.“ The rain was “big drops like a deluge of diamonds falling from the sky.” But Holstein also places you there, getting the color of the bedsheets, the smells of the food and the sounds of the day.

Toorpakai’s journey to Toronto turns out to be astounding. She was born at home in Bannu, a village in rural South Wazirstan in November 1990. She is a Pashtun, like Hashim Khan. Her family led an unorthodox life. Her father encouraged her mother to work (as a school principle and education consultant). For this, the Taliban threatened them. Their home was stoned and shot up with AK-47s; an intruder appeared inside once, with a handgun. Maria’s older sister Ayesha went to university and today is a member of Pakistan’s parliament.

Toorpakai was an unusual child. When she was still four, she burnt her dresses and insisted she go around as a boy so she could play outside. For a decade she passed as a boy. Sports were forbidden, especially for a tribal girl. She barely went to school, eventually getting expelled after her one sustained attempt. She was a feisty tomboy, quick to throw punches and happy running around with a gang of punks. She expended some of her energy in weightlifting.

Toorpakai was an unusual child. When she was still four, she burnt her dresses and insisted she go around as a boy so she could play outside. For a decade she passed as a boy. Sports were forbidden, especially for a tribal girl. She barely went to school, eventually getting expelled after her one sustained attempt. She was a feisty tomboy, quick to throw punches and happy running around with a gang of punks. She expended some of her energy in weightlifting.

At age twelve she started playing squash (to escape the Taliban, the family had moved by this time to Peshawar). Forced to produce a birth certificate, she came out as female. Many of the boys at her club harassed her. Her mother and father were the opposite of helicopter parents—her mother never saw her play and her father just once. She became the top female player in the country. She put on her first dress since the original bonfire to receive an award from President Musharraf.

But the Taliban again threatened to kill her. They left a death threat note on her father’s car. For a while snipers and guards tried to protect Toorpakai, but it became too dangerous. Violence swirled around her. Car bombs went off in front of her, people were shot. For nearly three years, she hibernated in her house, playing squash in her bedroom, and occasionally leaving for tournaments abroad like the World Juniors. (Going overseas was no picnic, either: she got dengue fever in Malaysia and spent a week in intensive care.)

At age twenty she bought a one-way ticket to Philadelphia. She says she was never as terrified as she was at the Delaware Open. That weekend she threw up and had panic attacks.

Then the way opened. Someone in Wilmington contacted her parents in Pakistan to tell them Toorpakai was more than miserable. Her father found a neighbor who had an old friend in Charlotte, North Carolina, a taxi driver. Unannounced the taxi driver drove up and collected Toorpakai.

In Charlotte, she checked her email. A message to Jonathon Power had come back with a phone number (Toorpakai had been emailing coaches around the world, looking for a place to train). She called the number. Power answered. A few weeks later, another one-way ticket, this time to Toronto.

That is where the memoir ends, with the start of her journey as a North American-based pro. Startling, sad and ultimately hopeful, A Different Kind of Daughter only disappoints because it doesn’t tell the story of the past five years. She has risen up in the rankings, to a high of forty-one and has won five tournaments. But at the same time, it hasn’t been easy. Power proclaimed she’d be a world champion and that hasn’t happened—she’s ranked sixty-six in the world right now. Moreover, how does it feel to have gone going from a scared girl in hiding to perhaps, after Malala, the most famous Pakistani woman in the world?

That is what a sequel is for.