By James Zug

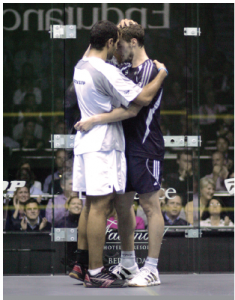

Amr Shabana was never absurdly dominant. The Maestro wasn’t like Jahangir Khan going five and a half years without a loss, or Heather McKay not losing a game in sixteen years. Shabana won one match in five and another in four en route to his last major, the 2014 Tournament of Champions. Even in his prime, it was so. In Bermuda as he went after his second world title at the 2007 World Open, he gave up points constantly; he lost a game in every round (two to Stewart Boswell in the second round) until the final.

And yet you knew he was going to win. It was an electric moment in Bermuda, when he walked out onto the glass court there, in the wind-swept parking lot outside the hotel. From the second he appeared, you just knew he was going to win, that he was going to chop Gaultier. And he did.

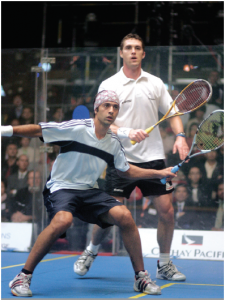

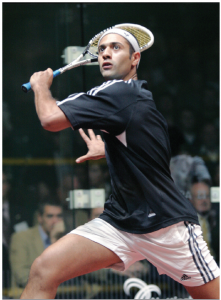

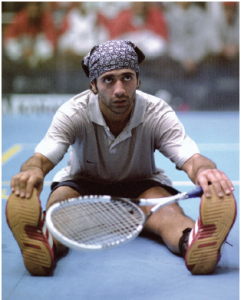

It was his style. Shabana was as Federer-like an athlete as I’ve seen on a squash court. The southpaw moved so effortlessly that he never seemed to sweat and strain; as he got older he stopped wearing the piratical bandannas around his scalp. He dove a lot as a young player—his nickname as a child was Grasshopper because of all his leaping and plunging after the ball—but even then it wasn’t frantic or desperate. He never seemed in a hurry.

Constructing rallies like no one else, he played tactical squash. He was patient and thoughtful, accumulating data, moving his opponent around, probing for weaknesses, his saturnine eyes taking it all in. This was backstopped by transcendent confidence in his racquet skills. How many times did Joey Barrington say, “the shot of the tournament” after witnessing a wrist-breaking Shabana shot? Has any player better negotiated that tense, flirting, knife-edge relationship with gravity? He was the one who started the tradition of cracking the cross-court volley nick as a return of serve. You see it all the time now, the gutsy, cocky, riposte. Shabana did it, in pressure situations, more often than anyone. And he almost always pulled it off. It was as if he climbed a long ladder and then kicked it away—all of us in the gallery could only wonder how he got there, up in the stratosphere, up where only the gods dwell.

It is hard to think back, but when Amr Shabana turned pro twenty years ago, all of that would have been impossible. Egyptian squash was at its nadir. The glory days of Amr Bey, Karim, Abou Taleb, were long gone. There were no women yet in 1993 not a single Egyptian woman was even ranked. Then in 1996 the glass court was plopped in front of the Pyramids at Giza, and improbably a teenager named Ahmed Barada reached the finals. Squash exploded in Egypt.

But Barada proved to be a flash in the pan, nervously tugging at his sneakers and disappearing in three years time. In his stead came the dozens of top players, Egypt becoming the best squash nation on earth. Two decades later Shabana is still the greatest of them all. He was the first Egyptian to reach world No. 1. He notched four world titles and thirty-three titles overall; he spent thirty-three months at world No.1 and 140 consecutive months ranked in the top ten in the world. None of the other Egyptians, as great as they are, are close.

Moreover, Shabana created a new model by going to college—he studied mass communications at the University of Cairo, finishing in 1999—despite a lot of scorn and doubt. Now almost all the Egyptians go to college. He was also a family man, too, first with his sister Salma (who coached him) and her husband Omar Elborolossy (who managed him) and then moving to New York and Toronto for a better life with his wife Nadjla and their own brood of three young daughters.

As he aged, he became the wise elder statesman, the guy players went to to get advice from, to hit with, to bend an ear, to talk about racquets or strings. He hung around backstage after practice sessions more than any other top player.

It was amazing he lasted twenty years. He had injuries and setbacks, the latest of which was a massive bout with hepatitis A he endured in 2013. He worked hard to come back from that at an age when everyone else retires. His latest injury, a bulging disc and muscle tear in his back, sustained at El Gouna in April, proved one too many and at age thirty-six, the Maestro put down his baton and walked off stage.