Earlier this summer, I went to my local club and got on the squash court with Richard Millman. An Englishman who has been coaching in the States for a quarter century, Millman is known for innovative, out-of-the-box thinking (he promotes the iMask, for instance). We played hard for about an hour. It was a big, sweaty workout. There were a lot of rails up and down the side walls and volleys into the nick and crosscourts and lobs. We had only a couple of lets and one stroke. It was a great match.

But we weren’t playing squash.

We were playing a game known, right now, as UK racketball. You play in a regular twenty-one-foot-wide squash court. You use a regular racquetball racquet—you know, the one with the wrist tether or wrist cord at the heel of the grip. (No one, yet, uses the glove.) Millman kindly taught me how to twirl the wrist tether around my wrist to get it out of the way of my hand.

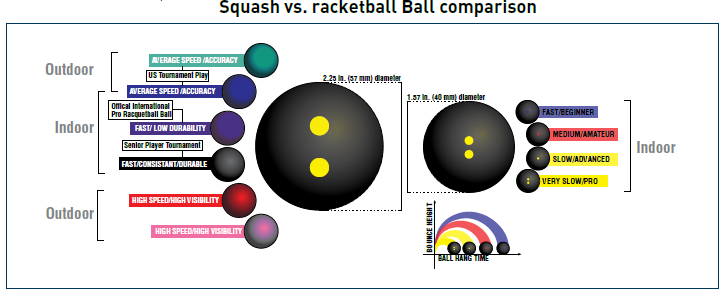

The ball in UK racketball is the key: it is a special ball, made for this game, a lot slower than traditional American racquetball. Four companies manufacture UK racketball balls: Price of Bath, Dunlop, Technifibre and Karakal. All four sell a blue ball, which is soft and slow (it bounces just about half as high as a proper racquetball ball does); and a black ball, which is faster and is usually used just for national championships. Nearly all the world’s racquetball manufacturers sell their racquets in Great Britain.

The rules, Millman explained, are pretty simple. You get two serves. When you serve, you bounce the ball, like in regular racquetball, and then you just have to hit it above the tin (no worries about the cut line) and into the service box (it can’t hit the back wall on the fly). The ceiling, unlike in regular racquetball, is not in play. Many clubs play to fifteen, point-a-rally; most competitions now are to eleven; two clear points for the tiebreaker.

UK racketball is the dirty little secret of squash in Great Britain. At some English clubs it is more popular than squash. There are leagues, national rankings, local tournaments, inter-county team matches, national championships. People play singles and doubles (in doubles, the ball has to be hit in rotation). So many people play that it is hard to know whether UK racketball or traditional squash is the dominant activity in squash courts across England. Andrew Shelley, the CEO of the World Squash Federation, plays mostly racketball at his club, Southgate Squash & Racketball. Some observers guess that more Englishwomen play UK racketball overall than squash.

Easier on the body, it plays the same role, in some respects, that hardball doubles does in the States. It allows older players to continue to play the game. And since it is easier to learn, it appeals to neophytes just getting into the sport, and people who are slightly intimidated by the gladiatorial, competitive nature of squash.

Fifteen years ago, when I was researching the history of squash, I corresponded with Ian Wright. He was a passionate squash historian and the honorary custodian of British squash archives. Every few months a package would arrive from Wright, stuffed full of old newspaper clippings and book excerpts. In one package was a strange memorandum he had written about a game I had never heard of: UK racketball.

In 1976 Wright visited the U.S., saw the booming sport of racquetball and came home with some racquetball equipment. He played it at Bromley Squash Club, his Kent club, which had eighteen squash courts.

At the same time another club in nearby Essex was starting to play racquetball. In 1967 Rex Guppy had founded the Kingswood Squash Club with six courts; eight years later he and his son Alister went to the U.S. Their original purpose was to meet with Miles Reilly, who manufactured platform tennis—paddle tennis—court and to investigate the idea of bringing platform tennis to Great Britain. Instead, like Wright, they returned with racquetball racquets and balls.

Both Wright and the Guppy family discovered, as Alister Guppy told me, that the game didn’t really work; that “the ball was too lively.”

Teaming up, they connected with Tony Gathercole, a rep for Slazenger/Dunlop and a staffer at a squash club chain. He got Slazenger to make the green ball, the first ball solely for UK racketball. Voila, a new version of squash. (Later they also worked with Derek Price, who ran Price of Bath, the old squash ball manufacturer in Warwickshire, to make balls—Price of Bath racketballs are still very popular today.)

In 1978 the Guppys expanded Kingswood to nineteen courts, making it perhaps the largest squash club in the world. People started playing this new game. “Progress was slow,” Alister Guppy said, “as still the long-term, die-hard squash players looked down their noses at this joke game played on ‘their courts’ but, as the squash players got older, many of the benefits of racketball became clear. It was also a lot easier for beginners to learn and less competitive, thus the image of this new game was not as intense and high impact as squash.”

The game spread, by both happenstance and forethought. “Squash was then flying high on a commercial basis as there were no health clubs as such and everyone wanted to join a squash club,” said Roger Cearns, a squash club owner in the 1970s and 80s. “The NSF, an association of commercial club owners, were worried about a threat of U.S. racquetball being promoted in UK in competition with our squash clubs, so UK racketball was adapted to the international squash court, simply by playing with a less bouncy ball. However, some clubs were using the USA ball so two variations grew up initially until the racketball ball was made more available.”

In the early eighties tournaments sprang up. John Treharne, who owned fitness clubs in England at the time, recalled that UK racketball helped with day-time court usage. “We had ladies’ mornings, league matches,” he said. “It was particularly popular with women and older men. We had better retention because of the social and less competitive appeal of the game.” Treharne won the national title in 1981, 1982 and 1983. He also pulled off a stunt. In July 1983 he and Steve Ryan played UK racketball for thirty-one straight hours at a club in Berkshire, raising money for charity and getting into the Guinness Book of World Records.

Another early adopter was the six-court Stourbridge Lawn Tennis & Squash Club outside Birmingham. The game arrived there in the early 1980s and took off, particularly among women. In February 1984 Wright, Rex Guppy and others convened a meeting at Stourbridge and formed the British Racketball Association. Seven months later, the English Sports Council recognized the BRA as the official governing body of the game; and in December the BRA hosted its first official national championships (Wright won the men’s 40+; the men’s open trophy is now named after him). When the squash boom of the 1970s and 80s had run its course, UK racketball was often a savior. At Stourbridge, the game boomed in the 1990s—at one point it fielded six teams in a day-time Midlands league.

At the same time, the public image of the game evolved. Juniors, men of all ages, even top professional players—all began to see it not as a hit-and-giggle distraction but a real sport. “For perhaps the first twenty years, racketball was certainly regarded as a separate sport for a separate market (females who perceived squash as too difficult/competitive),” said Zena Woolridge, a Stourbridger and currently president of the European Squash Federation. “But it has pretty much lost that separation now, and squash and racketball have blended together to effectively be one sport for everyone, played with a slightly different racket and ball, and slightly different tactics. The change in squash scoring from HI-HO to PAR also helped to bring the sports closer, as it made it easier for both to adopt the same basic scoring system.”

By the mid-nineties, over a hundred British clubs had enough interest in the game to affiliate with the BRA. In September 1998 the BRA merged with the Squash Rackets Association, the governing body of English squash since it was formed in December 1928. Instantly, the SRA added thousands of players to its rolls, which helped improve its participation figures when seeking British Lottery funds. “Racketball is very easy to learn,” Stuart Courtney wrote in Squash Player magazine after the 1998 merger, “is a wonderful nursery for beginners and tends to be played during the day by young women with family commitments and players who are now finding squash too difficult. It is also attractive to court owners because it tends to be played at times when squash courts are traditionally empty which, in turn, keeps the courts from being closed for development into gymnasiums and aerobic studios.”

In February 2009 England Squash renamed itself England Squash and Racketball. “It was surprisingly uncontroversial within the Board, or ESR Council or AGM,” said Woolridge, who was the chair of ESR from 2006 to 2012. “One of the main drivers for the name change was that racketball was played in lots of clubs (even if it was patchy), and we felt that if England Squash didn’t take ownership of the ‘commercial’ property, someone else would. And it might become quite difficult having two different governing bodies managing two sports occupying the same squash courts. So, one might say it was protecting our territory, but it also made business sense.”

At one point after the merger, ESR had forty people on staff but just one, Matt Baker, had it in his portfolio: he was in charge of the South West of England and also everything for UK racketball. According to Philip Wright, an ESR administrator responsible for UK racketball, the ESR are starting a series of regional closed tournaments leading up to the nationals and are promoting the game to leisure center owners and to U3A groups (University of the Third Age, an international group for retired people). As of yet, there are no junior rankings or university teams.

The real story about UK racketball is the grassroots. Everyone involved with the game notes how it has been mostly a case of benign neglect by the powers that be. The game grows outpost by outpost, by word of mouth, one club at a time. “When I was growing up my club used to do a UK racketball tournament on Boxing Day,” remembered Tim Vail. “There was free wine and cheese, and I’d tag along with my parents. As a child, that was the one day of the year we’d play. It was a bit of fun.” After university, Vail took up UK racketball. His first tournament was the 2001 nationals, which he won. He’s gone on to notch six national titles. “Years ago, a lot of squash players didn’t like it,” he said. “They thought it was a rubbish game. But in time, they see how it keeps people in the game.” When he arrived at Lee-on-Solent in 2006, there were two UK racketball league teams and eighteen squash league teams; now, almost a decade later, there are thirteen UK racketball teams and eight squash league teams.

In Exeter in 2009, a club brought in the game and in eighteen months had to convert a gym (originally a squash court) back into a squash court because of the demand for court time. “It’s easy for kids to take up with a short racket and bouncier ball, and it prolongs active life for those aging squash players whose limbs are not working as well as they used to,” said Alan Thatcher, the longtime squash promoter and friend of Ian Wright. “Some UK clubs are reporting such a growth that racketball occupies more court time than squash. We treat racketball as a fun extra, and there seems to be an easy, friendly cross-over, despite some squash diehards saying we are going over to the dark side when they see the racketballs and short rackets emerge from the bag.”

The Selby clan learned it growing up at Kingswood. For a time, they just used squash racquets and the UK racketball ball. All of them play. Daryl Selby, currently world No. 15, has won six national UK racketball titles. In one final, he beat Peter Nicol, the former world No.1, 3-1. Lauren and Elliott, Daryl’s siblings, are keen players. Elliot got to No. 3 in the British rankings and has won the national doubles; he and Lauren have won the national mixed. “It was first a way to continue to play with my father,” Daryl Selby said. “I was beating him at age fourteen. It has helped me be more aggressive It is a good way to keep your eye in the game without getting hurt.” Elliot Selby, world No. 341 in squash, agreed: “I actually played it more than squash for quite a while as I liked the exercise—the rallies go on—and the different tactics you can use.”

Whatever administrative acumen is being applied to the game comes from two Englishmen. A half dozen years ago, Mark Fuller, a thirty-year-old squash player (currently world No. 149), stumbled upon UK racketball at the Hallamshire Squash & Racketball Club. Fuller was playing professionally full-time but not making enough money to survive. “Instead of getting a job in a bar or working in a shop,” he said, “I looked at squash—loads of people doing so much there; but racketball, no one was doing anything.” He built a mini-business: a website (uk-racketball.com), with tournament results, coaching tips, news; a Twitter feed; and in 2010 he started running UK racketball amateur tournaments—he now runs eight a year. All are popular and sold-out. “For older players, it is very good,” he said. “The same tactics, same movement as squash, but basically slower. For beginners, squash is like serving is for someone learning tennis—it is just hard. But with racketball, you get to run around right away, get a sweat. For the new player, racketball is a much easier sell than squash.”

Fuller v. Vail is the main rivalry at the top of men’s UK racketball. In the finals of last year’s nationals, Fuller was up 2-0 and 8-3 in the third and lost in five. They have brutal rallies—one last year lasted 147 strokes. “I really enjoy playing the game,” Fuller said. He now has a staff of two full-time workers. “Mainly, it is like squash: it is about the people.”

The other leader, also by happenstance, is Rob Shay. A Zimbabwean by birth, Shay came to Great Britain in 1976 and has spent the last thirty-five years coaching at Edgbaston Priory, the giant Birmingham squash club founded in 1875 and now with ten courts. When he was forty-five, Shay stopped squash competitively because of hip and knee trouble. He was on the verge of a hip operation. Now, because of UK racketball, he is still on court at age sixty, surgery-free, playing UK racketball regularly. “It was seen as an old ladies game,” Shay said. “The men didn’t want to be seen playing. But now everyone knows how good it is for your body. Good players use it as a coaching tool: it teaches patience and how to really create openings, not trying to snatch things too early.”

A few years ago the UK racketball nationals were in Cambridge and came off poorly: only the best players were invited, there were no directions available to get to the club and the draw was a mess. Shay offered to take it up and since then has run the nationals at Edgbaston in the late spring or early summer. They are a very robust event, for British standards, with 300 entrants.

Doubles is still a bit of a random game for UK racketball. “It is harder to have a serious influence on the point, with four people on a small court,” Tim Vail said. “It is just harder to move players. I personally don’t like it that much.” But others enjoy the fun of having a partner out on the court. Even USA Racquetball has taken note of the strange hybrid thriving across the pond. “I’ve gotten curious about it,” said Steve Czarnecki, the CEO of USA Racquetball. “I’ve gotten some balls and played. It was fun, I ran a lot more, the rallies were longer.”

In the end, the one thing wrong about UK racketball is that it isn’t really racquetball, it is just a form of squash. It is much like the difference a quarter century ago between hardball and softball—it isn’t the ball that ultimately makes the game or even the racquet but the court. And there is a strong resistance in the U.S. to a game with racketball in its name, no matter what the spelling. Richard Millman suggests calling it big ball squash. Others offer big squash. Or squabble. Whatever the name, it could be the next big thing in American squash.

What Fans of UK Racketball in America Say:

It is a great game. It teaches racquet preparation. There is less dynamic lunging. It is a fantastic cross-training sport. You can stay healthy. Your legs don’t get inflamed. It saved my career. I was fifty years old. My meniscus was shot, a big tear in it, and I thought my squash-playing days were over. I was back in Norfolk, England. I saw the game. I started to play. The rallies went on and on. Tightness and early preparation were rewarded. My knee slowly felt better. You can’t get fit playing squash—you have to get fit to play squash. That is the old saying. But you can get fit playing UK racketball. We should adopt the game as our own. In my opinion, properly handled, it could be the savior of squash.

—Richard Millman

I am a huge fan of UK Racquetball. I play mostly in the off-season. Every now and again I will play in the fall or winter. Mainly I use the game as a fun way to get a great workout. I find that it does not get your heart rate up to a strenuous workout (like the fast pace and change of direction in singles), but the rallies last a long time and the constant running and moving create a solid workout. After the matches I am usually drenched. But my legs, especially quads, butt, ankles, feel great and I am able to still play some singles later or add another workout to the day. Physically it is a great game to play for all ages, especially those that may not like to play singles due to the strain it can cause on knees and other joints. So much better than the elliptical. Also, the swing and hitting of the ball is fun to mess around with. You can use all sorts of spins and swings to move the ball around the court. You must be exact with certain shots or else the ball spins off the wall and gets into the middle of the court. This makes the game interesting and fun for me because it brings elements of singles and doubles into one game. It’s an extremely fun game with the amount of focus you need to hit the correct ball when playing good players. Anyone can pick the game up as well because of the size and bounce of the ball and the large racquet size of a racquetball racquet. The workout can be an exhausting one or a simple sweat but the body always feels better afterwards compared to the physicality of singles.

—Greg Park

In the 1990s, the club I was training a lot at was Racquets Fitness in Thame, just outside of Oxford. Simon Martin, now the owner, was playing in the European Open in England and I tagged along as a seventeen-year-old. I lost in the quarters while Simon went on to win the event. The following season, I played Nationals, which I won, beating the defending champion in the first round 3-1. Since then I didn’t drop a game in a singles match and remained undefeated until I moved to the U.S. in 2000. I was in the Guinness book of world records in 1999 for most national racketball titles won. I won at least two men’s doubles, two mixed doubles and somewhere around five or six singles titles I think. I was also playing the PSA tour, which was where the challenges waited. A number of the ranked squash players gave the racketball nationals a go. I played a number of PSA ranked players in exhibitions, some in Germany and France when were trying to grow the game in Europe. During my time playing, we experimented with a number of different black, red and blue balls made by Karakal, Price, Dunlop, all trying to find the right balance of durability and bounce characteristics. I have had people play it in Cleveland and at the Cincinnati Country Club and they all enjoy it. Great fun game. Would love to see it grow in the U.S. I tried the U.S. version of racquetball, and the rallies are just too short. No work out or tactics. Back at Racquets Fitness, there is more racketball played now than squash. It was at least 50/50 when I was back in Lee-on-Solent, Brian Patterson’s old stopping grounds a couple of years ago and home now to Timmy Vail. Dunlop/Slazenger took notice of the rise of Racketball before England Squash. Around 1995 they sponsored Tim Henman, England Tennis No. 1, Simon Parke, England Squash No. 1 and they wanted me as England No. 1 in racketball to sign for them for squash and racketball; which I did. They also went after the badminton No. 1 to have all the racquet sports.

—Nathan Dugan

I was introduced to UK racquetball last summer by my good friend Hal Tendler who plays at the Greate Bay Club in Somers Point New Jersey. He and I have played several times. He plays on a regular basis with the GB club pro and touring doubles pro Greg Park. I have to admit when Hal first was trying to get me to play with him, I thought he had invented a new game that he imagined he could beat me in. I liked it from the start, although it took a little getting used to. Being a true squash snob, telling people that I was playing UK racquetball did not roll off the tongue smoothly; in fact, at times it was just easier to tell people that I had been playing squash. Eventually I got my own racquet and balls from Harrow, thanks to Dave Rosen, and started playing once a week (Mondays when the golf course is closed). My line to everyone that I ask to play is, “do you have an open mind?” They are all always a bit curious, so they give it a try. One night I was playing at PCC and a half a dozen people who were playing doubles, each came on for a game to try it out. I have gotten a few highly ranked juniors to play, like Matt and Brian Geigerich and Brian Hamilton. They seemed to like it and picked it up pretty quickly. Eric Pearson, an accomplished racquets (of any kind) athlete was very curious to try it when he came back from San Francisco to Chestnut Hill recently. As I suspected he also picked it up quickly. UK racketball is probably the farthest thing from hardball singles, and yet I believe I heard Eric utter, “This may get me back on the court.” I like it because it is a great workout and a new challenge. I recommend it to people as a game they could play to get exercise when rehabbing from an injury, because you can glide more smoothly to the ball, as opposed to the much faster softball squash game. It is also a game one could still enjoy with their non-dominant hand if there is an injury to the dominant hand. Anyway, I like it and will continue to play it in the late spring and summer, as long as I can get people to give it a try. I keep three racquets on hand so I can loan them out. —Rich Sheppard

The perfect game for the aging squash player. I am not suggesting we’re aging but having just played UK racketball, I feel great. No aching bones like I’ve just played squash, just a great workout and some of the same challenges of squash. As you may be aware I am a fan of inducing pain on my opponent and UK racketball allows me that great thrill of a slow death.

—Dominic Hughes

I played for a season in the UK—mostly during breaks from coaching at the England National Squads. I played David Campion who was a former World Junior runner up—lost to Parke in Paderborn 1991. So not very often (once a month), but enough to learn nuances with regard to striking, movement, ball spin, etc. Played the Nationals once at the end of that season and lost in the final to Daryl Selby. Loved competing at something different and the fact there were no decisions from referees—my main gripe about playing any competitive squash after retiring. I was done with that level intensity/desire/desperation. Also played so many different players than my normal events–these were mostly high-level amateurs, club coaches or at the very most lower-ranked PSA players. The only exception was Daryl in the final. The event was at Edgebaston Priory, Birmingham, England. I believe it helped my squash game—despite having already retired—as you could get away with being less accurate and running around more but I was tired of that style of play for obvious reasons. Therefore, I really focused on playing smarter, staying on the shot longer and being very deliberate with where and how I hit the ball. From a technical point of view it certainly helped my follow-through as that was vital in improving the racquetball shot. I also varied between a flat racquet face or completely open one hitting with large degree of slice/cut, the normal squash open face did not really work for me either hitting short or long. I really enjoyed playing the game as it gave me a great workout but without the harshness of the squash type lunges, so I finished games feeling tired but not hurting physically.

—Peter Nicol