By James Zug

Jesus David Flores is the youngest of four brothers. He is eleven, a fifth grader, a wiry, fresh-eyed, inquisitive kid. His father is a mototaxista—he drives a motorcycle taxi around Cartagena. Jesus joined Squash Urbano Colombia in December 2014, a couple of weeks before the program officially started.

He has fallen completely in love with squash. He comes to every one of his four weekly practices. He comes to optional practices. When a practice is over, he leaves and goes home like the rest of the students on his team; a few hours later he reappears at the courts during another team’s practice, wanting to play some more. He plays alone. He plays king of the court. He plays matches. His English isn’t that strong: when we played a match, we had to use sign language to keep score. This summer he came to the U.S. to play in the urban nationals. On the ride north from New York to western Massachusetts, he sat in the back seat of a car, talking with a CitySquash boy for three straight hours. Both used English, their second language, and squash, now their third language.

“Jesus David has been highly involved in all aspects of our programming,” said Esteban Espinal, the executive director of SUC. “ He’s the perfect example of someone who loves exploring new things like squash and learning English. His behavior and temper are two things he needs to improve, and we are working closely with him on that, but his passion for squash is amazing.”

Helping widen the horizons of Jesus David is the goal of Squash Urbano Colombia. Esteban Espinal is the founding force behind SUC. Now in his mid-thirties, he grew up playing squash in Bogota. He played No. 2 for the Colombian national team at the World Juniors in Milan in 2000 (the team, headed by Bernado Samper, finished 14th, Colombia’ s best-ever result, even after squandering clinching match points against 12th-place Netherlands). After college, Espinal moved to Toronto and played in a few pro tournaments (his highest world ranking, according to SquashInfo, was exactly 300) before landing at Club @800, the two-court Westchester facility. As so often happens in the U.S. these days, Espinal eventually became a private coach for a local family.

In 2009 he switched gears and joined CitySquash, the after-school youth enrichment program based in the Bronx. “I had a chance to go coach squash there, and it was the best thing that ever happened,” Espinal said. “I loved the program, the kids. I loved working with Bryan Patterson—he was a real mentor. I got really involved with the kids and their families. One year I took CitySquash kids to eighteen tournaments, eighteen different weekends.”

In 2013 the idea for an urban squash program in his native Colombia popped up. The origins of the program are on a napkin, now lost, upon which Espinal and Samper scribbled a few ideas while talking for a couple of hours one day in Westchester, way back when they both were teaching pros there. The idea on that lost napkin bubbled back up after Tim Wyant, the executive director of the National Urban Squash & Educational Association and Espinal’s former boss at CitySquash, returned from a Jesters squash trip to South Africa emboldened with the idea of urban programs outside the States.

A few months earlier, Espinal had gone to a wedding in Cartagena. One day he wandered into Complejo de Raquetas, the one sizable squash facility in the city. It was a complex of seven open-air squash courts, eight tennis courts and a small set of offices built by the government for the 20th Central American & Caribbean Games, which were held in Cartagena in July 2006. Since the Games, the squash courts had lay more or less empty: a pro, Deison Ramirez, worked there part-time, but there was little play.

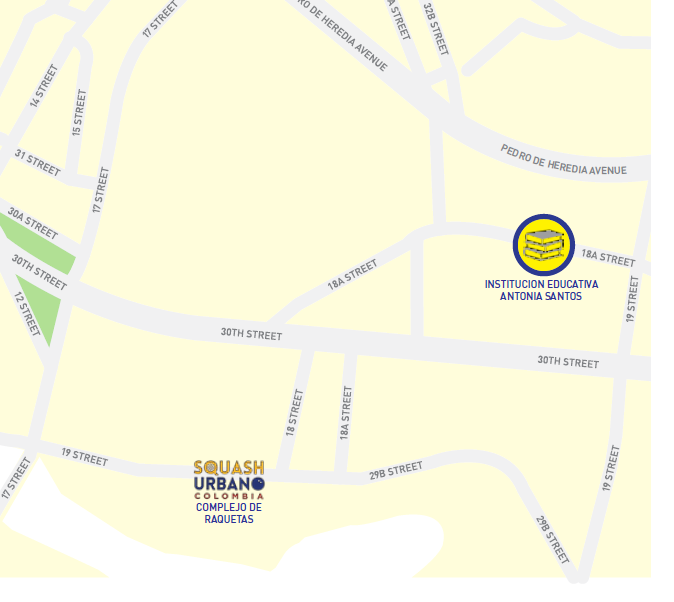

The courts are ideally located. They are in a district dominated by the city’s landmark: Castillo San Felipe de Barajax, the sixteenth-century fortress, with its weathered stone walls, mazes of dark tunnels and a colossal Colombian flag whipping in the breeze. The courts are also just down the street from the offices of El Universal, the city’s daily newspaper where Gabriel Garcia Marquez worked in the late 1940s. (On one of the days I visited the program, a photographer from El Universal came to shoot some of the SUC students for the typical, first-article-in-local-newspaper that ran two days later.) A four-minute stroll around the base of the fortress leads to a perfect partner school, Institucion Educative Antonia Santos, a neighborhood school with many underserved students.

NUSEA was beginning to collaborate with international programs—particularly those in Toronto, Johannesburg and rural India—but these were already established. Espinal was suggesting that NUSEA start an overseas program from scratch. “After working at CitySquash for five years, Esteban approached NUSEA and spoke about his long-held dream of starting an urban squash program in Colombia,” said Wyant. “Given his experience in urban squash, his roots in Colombia, and his unyielding determination, it was not difficult to say yes.”

“It was still a big risk for everyone,” said Espinal. “I had lived in the States for ten years. My family is here. And I loved CitySquash. But this was such a tremendous opportunity.” For the next year, Wyant and Espinal made three trips to Cartagena to put the pieces in place and build a community of supporters in the U.S. and Colombia.

In 2014 the effort accelerated. NUSEA hosted a launching party in New York that was a rousing success, attended by hundreds and raising $57,000. A board coalesced around the leadership of Diana Kopp Gomez. A Bogota native, Gomez went to Hotchkiss and Harvard, playing squash recreationally there. As an adult dividing her life between New York and Bogota, she continued to play a lot of squash. “People kept on coming up to me,” Gomez said, “and they’d say, ‘Have you heard, have you heard about Squash Urbano Colombia?’ and how I would be the right person to get involved.”

Another early catalyst was the involvement of the Colombia Squash Federation. In 2014 its president, Pablo Serna, jumpstarted the project by accessing government funds for overseas travel for junior athletes. Seven young Cartagena kids, all brand-new to squash, were brought into a pilot program at Complejo de Raquetas and then taken on a two-week trip to Malaysia. They attended the Malaysian Open in Kuala Lumpur and trained at Nicol David’s squash club in

Penang. “It was an amazing trip,” said Espinal. “None of the kids had ever been on an airplane before. It was an amazing cultural experience, the music, languages, food—a couple of them tried frog legs. Most of all, they trained with top players, watched top players, saw how squash could literally take them anywhere.”

In the summer of 2014, Espinal and his wife Juliana (a native of Cali) moved back to Colombia. With the seven players serving as the core of SUC, the program expanded with tryouts in the fall and it officially launched in January 2015. The program is very similar to American urban programs, but with fascinating adjustments. The children come throughout the day because the school day at Antonia Salas runs for twelve hours and students come in shifts. The SUC kids have large gaps when they are not in session; thus, the courts and classrooms hum from seven in the morning onwards. English fluency is a primary goal, as the students don’t have much of an opportunity to learn the language at school, and tourism, Cartagena’s number-one industry, is based in English.

When my family went for a visit in February, we were amazed at the enthusiasm for the program even though it had officially only been going for a couple of weeks. I made the short trek from the courts to the school and back with Espinal—he ends up walking that route a half dozen times a day. The children love the squash—they even regularly hop on court four, which is a twenty-five foot softball doubles court. The facility buzzes with life. More and more locals are coming out, including players in a new squash club at the local university. There is energy and conviction, and a real hope that this experiment in urban squash is just the beginning. Already there are mentions of other cities in Colombia and other countries where a program would be successful. “NUSEA couldn’t be more pleased with how well SUC is doing, and we’re hopeful that we can establish similar partnerships with leaders like Esteban in other countries,” Wyant said.

Cartagena is a classic tourist destination. In its impossibly quaint old city and the reviving barrio of Getsemani, the former slave district, it drips with history, culture and an easy, Caribbean charm. The safe and secure atmosphere and direct flights from New York have meant that dozens of Americans have now visited the program. More are coming in 2016, when NUSEA plans to host a board retreat at SUC. “I should run a travel agency,” joked Espinal.

The program is also moving in the other direction: a group of five players, including Jesus David, came to the Urban Nationals in Williamstown in June. They spent a few days in New York, visiting Freedom Tower, Chinatown, Times Square. Even in the summer heat and humidity, they never took off their New York City sweatshirts.

The two full-time SUC teachers—Franchesca Caceres and Lizeth Casallas (both doing a year of field work in their fifth and final year of teacher training)—are very positive about the children’s focus on academics. The kids not only get tutored on their homework but are also studying four areas: local history, the arts, the environment and running a book club.

The squash, for players like Jesus David, is such a potent lure. SUC parents like it too. One morning, Vivian Gomez Pajaro, the mother of Brendi Ramos, a SUC fifth-grader, sat with me in a classroom and enumerated all the benefits of the program. “We like the academics and that they are learning English,” Pajaro said, “but I want Brendi to win. I want her to become a great squash player.” She paused and then looked me in the eye. “I want her to become a champion.”