By Richard Millman

Picking up from last month, we will now address the critical differences between future, present and past on the squash court.

First, mechanically speaking, when one moves continuously the legs are necessarily engaged and, as they are the most powerful of our limbs, they can cope with the stresses created by the generation of force much better than our arms.

Without movement the legs are static and do not produce the necessary energy to play the ball. Being static leads to a paltry attempt to generate power from the arms and upper body which, in turn, produces tension and stress that the arms and hands cannot cope with and remain precise.

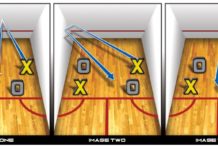

Additionally, if a player is static when striking the ball, the ball (the game) is propelled into the future, leaving the striker in the past, trying to play catch up.

This, in turn, leads to many of the interference problems of the modern game, as subsequent to the ball moving into the future, the player desperately attempts to regain position after the event, while the incoming player—who wishes to keep up with events—is attempting to gain access. The conflict is obvious. If I am trying to get away after the event and you are trying to maintain your current relationship with events, there is bound to be a problem.

When players attempt to ‘complete’ the shot, they allow their Temporal Gaze to become distracted from the flow of the game and become involved in an irrelevant matter—the importance (in their minds) of hitting the ball well. This is both misguided and mistaken. It is misguided because remaining in place after the ball has gone leads to a loss of place (getting behind) in the flow of the rally and the conflicts with opponents. (It is perfectly feasible and actually more correct to ‘complete’ the shot as a part of the movement toward the next phase of the game.)

It is mistaken because it just isn’t the most effective method. Were we engaged in an attempt to propel a piece of rubber down a wind tunnel at maximum velocity we could perhaps be forgiven for dwelling in place after the ball has gone—although it is a simple fact of physics that one cannot transfer one’s weight into a projectile as effectively standing still as one can dynamically on the move—but we are not. Our job is to stay up to date with the game (the ball) physically. The most effective way to do that is to be a little ahead mentally.

The concept of attempting to hit a shot that your opponent cannot get is futile and extremely ill advised (it is perfectly satisfactory to attempt to hit a shot that is ‘difficult’ for the opponent— just not impossible.) The fact of the matter is that most competent opponents retrieve most shots. So our assumption must be that our opponent will retrieve every shot. That being said, we must therefore always prepare for the worst and hope for the best.

If we ever prepare for the best and not the worst, we will be guaranteed to get caught unawares.

It is for this reason that we must keep our Temporal Gaze always in the future, ready to deal with all possibilities. If by some chance the opponent fails to retrieve the ball then we have created time by being ahead—which we have to spare. Far better than attempting to finish a rally (focusing solely on the shot we are playing) and then being unprepared for the ball to be returned.

It is perfectly fine to attack ferociously—provided you always plan for the attack to be returned and position to defend accordingly— AS you execute the attack—not AFTER.

So no matter whether you are playing squash, organizing your final thesis, or organizing a staff rota, ask yourself: where is your Temporal Gaze being directed on the time line? Past (you can’t keep up); Present (you are hoping your current actions will be adequate to complete the job—a recipe for disaster); or Future (do your very best but expect the unexpected and always be prepared to keep going.)