By Richard Millman

Are all of your efforts combining to keep you in the best place on the time line of the game—and of your life?

Tempus Fugit, the old Latin maxim goes (literally: Time Flies) and as it does, so must we—or get left behind.

Ask any elementary school kid whether they want to be ahead or behind in a race and they will tell you they want to be ahead.

And yet much of what we are told to do and decide to do has the opposite effect and results in our finding ourselves very much behind.

In all fields of achievement, our sport of squash included, learning to develop and control your ‘Temporal Gaze’ is a key element of success.

What is ‘Temporal Gaze?’

It is the point in time where your attention is directed and maintained.

The Temporal Gaze of an expert tends to be directed toward the furthest possible point into the future on the time line continuum, whereas a novice finds their view falling farther and farther behind as they find it difficult to keep up with events.

Events happen in the present and rapidly become a part of history—the past—so the ability to be prepared for events and to proactively have solutions and actions in hand, ready to deal with multiple possible events, is an important asset in the competitive world.

In squash, the game and the present are located in the ball. Wherever the ball is, that is where the game is.

Our behavior as squash players must allow us to keep up with events (the game) and be constantly flowing into the future so that we don’t get left behind.

Therefore, the accepted wisdom of the past, which directed players to focus on the execution of single events—a shot, moving to a fixed place, attempting to finish a rally—has unwittingly led to an interruption of flow.

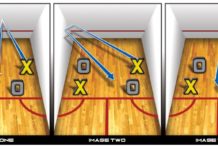

The great players try to consider the consequences of their actions before they execute them and always plan proactively for the next phase of the game after the one they are currently engaged in and, in fact, are in transit on their way to the next position as they are completing whatever their current action is.

This of course benefits them greatly for multiple reasons. But even great players can be victims of static thinking. For instance, Hisham Ashour once told me that he and Ramy loved it when James Willstrop had an opening to go short. Why you may ask? Isn’t Willstrop brilliant at the front of the court? Yes he is, but that is precisely why he has been vulnerable there. Because as soon as James became confident in his ability to play winning drop shots, he allowed his defenses to marginally drop as he foresaw the possibility of ending the rally. Once he envisioned the end, his proactive planning decreased and Ramy could use the momentary dropping of James’s guard to counter attack.

What are the advantages of being continuously on the way to the future (mobile) rather than dwelling in the present on the execution of a single activity (static) as a squash player?

Next month we will go into depth on the critical differences between the future, present and past on the squash court. In the meantime, pay attention to players who play their shots and stand still after executing them. You will begin to understand the difference well and the continuation of this topic will make a lot of sense.