By Richard Millman

Camels are strong animals. Over eons they have evolved into beasts of burden with amazing endurance.

But even camels have a breaking point.

Now imagine an improbable competition between a couple of camel merchants who decided to test two unfortunate camels’ capacity to withstand pressure and which one of them could break their camel’s back first.

They agree to test the camels by placing a load of straw on the camels’ back and then adding one straw at a time until the camels’ backs broke.

One of the merchants decided to stop after placing each individual straw to see if the camel’s back would break. He placed the straw with the maximum force he could muster each time and eagerly expected to see the unfortunate animal collapse. Each time he stopped to check the results of his effort, the camel, feeling the extra weight, simply shrugged the extra straw off of his back reducing the burden to its original weight and sometimes even less.

Each time the merchant, having hoped that he would finish the competition with the straw he had added with such vigor, was disappointed and, having stopped building the straw burden on the camel’s back in the expectation that each straw was the final straw, he then had to spend time building up his hopes and efforts for the next attempt to break the animal.

The other merchant thought his camel was an extraordinary beast and realized he was incapable of predicting how many straws it would take to break its back.

Therefore, he continuously added to the burden, adding straw after straw, fully expecting the camel to bear the burden, unaware of when or if the animal would collapse—but determined to continually add to the animal’s difficulty.

Of course the camel felt the extra weight and tried to shrug the extra straws of its back, but the merchant continually added straws at a rate that the camel was unable to keep up with.

The merchant was busily focused on adding one straw after the other, fully expecting the camel to bear the burden when, just as he was about to add another straw, to his great surprise, the animal collapsed.

Obviously this is a somewhat contrived story, though I am sure you have often heard mention of ‘the final straw’ or even of ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back.’

What does this mean in squash terms?

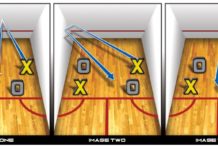

Very simply this: squash is a continuous activity.

We must not try to hit winners, because the concept of a winner is that of a finite stroke—the last straw—and we know it is impossible to predict when that might be. Even worse, if we attempt to create the last shot, we automatically cease our efforts because we think the rally is going to come to an end—so we stop planning for the future.

The word ‘winner’ describes a consequence, not an intent.

You know that any opponent worth playing is going to retrieve most of your shots, so you should operate under the assumption that they will always survive your attacks—and that you should be prepared for that by expecting to have to continuously retrieve their shots and have to play another one yourself.

You should attack whenever that attack doesn’t leave you vulnerable and, indeed, should consider your own vulnerability when designing your attack.

You should assume that your opponent will shrug off your pressure but keep building it in the hope that you can build it faster than they can defend against it.

You will never know when your opponent will succumb and, ideally, if and when they do, you should be so focused on adding your next piece of pressure that it will be something of a surprise when you break their back.