By James Zug

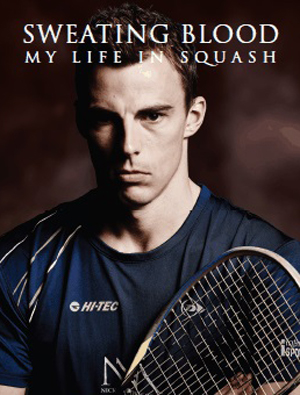

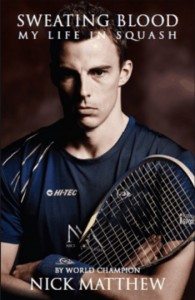

Nick Matthew

Sweating Blood: My Life in Squash

Cheshire, England: internationalSportGroup, 2013

It is a shame but inevitable. Like everywhere else in their careers, Nick Matthew and James Willstrop are now placed side by side on the bookshelf. Just under two years ago, Willstrop came out with his memoir, Shot and a Ghost [reviewed here in August 2012] and now Matthew has penned his autobiography.

In October in Philadelphia, I asked Matthew what was the catalyst for writing his memoir and he bluntly said, “I didn’t really think about doing one until I heard about James’ book. I thought, ‘I can do this too.’”

In October in Philadelphia, I asked Matthew what was the catalyst for writing his memoir and he bluntly said, “I didn’t really think about doing one until I heard about James’ book. I thought, ‘I can do this too.’”

While Willstrop did his memoir himself, with only a little editing from the squash writer Rod Gilmour, Matthew farmed it out in the traditional manner: he hired a well-known British journalist in Lon- don, Dominic Bliss, who spent time with Matthew in his hometown of Sheffield. Together they went running and biking and sat for hours of interviews, which Bliss turned into a narrative. It was then published by internationalSportGroup, the squash management and promotion firm run by Paul Walters. (The same month as Matthew’s book came out, Bliss also published a self-help book, A Man’s Guide to Having a Baby, but his most well-known book probably remains Drinking Games: One Book, 25 Games, Just Add Booze.).

At age nineteen Matthew switched from his childhood coach (awkwardly; they have no relationship now) to English guru David Pearson and became an all-time great: a world No.1, a three-time winner of both the British Open and the World Championship and a gold in the Commonwealth Games. Willstrop, on the other hand, has continued to have a wonderful career, reaching world No.1, but he has, so far, failed to win any of the big three events (the closest he’s come was squandering two match points in the fifth game of the 2008 British Open final against David Palmer).

Moreover, in the past six years, Matthew hasn’t lost a match to Willstrop, except two league matches in Europe. Excluding league matches, it is a total of twenty-two straight wins. It is one of the most extraordinary streaks in pro squash history and speaks to the psychological nature of the game.

In Shot and a Ghost, Willstrop hinted about what had happened in the finals of the 2009 British Open, referring to sledging (the cricket term for quiet verbal insult and abuse), while Matthew devotes most of a long, revealing chapter to the match and their fiery relationship.

Much of the book is like that. Matthew explores his career in detail and with surprising candor. The book has a laddish tone. It is studded with British slang: “handbag” moments, keeping “schtum” “knees-up” parties, “jiggery-pokery,” “gyp,” “anorak,” and “under the cosh.” Matthew also has a deeply ingrained sense of humor. The chapter titles are ribald: “Snoring Rhinos,” “Dirty Sanchez” and “Eight Malaysian Prostitutes,” and each chapter begins with a faux-eighteenth-century prefatory introduction: “in which our hero takes on more ladies than he can handle, very nearly falls foul of Belgian police, loses a pair of his trousers in the Indian Ocean, gets punched by a Swede and wakes to find his roommate has soiled the hotel bathroom.”

As the chapter titles suggest, Matthew (perhaps with Bliss’ encouragement) delights in reporting on the off-court escapades he’s been involved with—some legendary on tour, and some hitherto kept secret. He chucked an American football at Greg Gaultier’s red-dyed head at a raucous Princeton eating club party after the World Juniors in 1998 (he missed). He laughs about the winter night that Adrian Grant slept in the trunk of Matthew’s mother’s car (not comfortable); and he retells the notorious tale of the time in Hong Kong when Simon Parke and Graham Ryding “decided it would be clever to test their post-drinking coordination by running down a street on top of all the parked cars.” He also lets readers know that on the perennial issue of whether to have sex the night before a match, he comes down firmly on the abstinence side of the ledger.

With a grin, Matthew tells about how poor a driver he is—quite a lot of “prangs;” how he farted on court in the 1999 World Open (Jonathon Power famously asked for a let mid-point and was denied; oh, for Video Review back then); and the annoyance of drug-testing (the tester comes into the stall with you).

But there is a serious, pedagogical side to the book. He talks about the training he endures—hence the title—and the way he prepares for matches. He also examines his relationships with his team, especially his father (a physical education teacher) who still strings all of his racquets (twenty-seven pounds tension), his new wife Esme, his coach David Pearson and his psychologist. Matthew’s nickname is “Wolf” and his psychologist has helped him learn to ratchet down to what he calls the Assassin mode, cooler and more mentally economical.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that in this reality-show, confessional era, we have memoirs from two of the top players in the world (and rumors of a few more forthcoming). We are lucky that these two are so engrossing and revealing.