By Richard Eaton

Photos by Steve Line/Squashpics.com

It was one of the three or four greatest World Championships surprises of all time. Those who witnessed the U.S. Open final only sixteen days before might rate it rarer even than that.

The courage and discipline that carried Nick Matthew to a highly charged victory over Gregory Gaultier in the final in Manchester may also seem improbable to those who witnessed the Englishman’s rapid loss to the Frenchman in Philadelphia.

There Matthew earned just fourteen points. Here he survived emotional turmoil, physical pain, controversy, and startling twists of fate over 111 dramatically unpredictable minutes to take the world title by 11-9, 11-9, 11-13, 7-11, 11-2. Not even Matthew—self-confident fellow though he is—had expected anything like that.

At thirty-three years and three months, Matthew was only a few weeks younger than the oldest male world champion, Geoff Hunt—the great Australian. Though Matthew has never had to cope with someone like Jahangir Khan as did Hunt, his achievements have come in an era when squash is far more explosive and the tour’s schedule far more demanding.

Matthew, seeded fourth, had to overcome plenty else as well. He had to claw back deficits of 6-9 in the first game and 6-8 in the second, overcome the aggravation of having a good lob called out at an important moment in the third game, recover from an accidental blow in the face from his opponent’s head, and erase the worrying memory of a missed match point in the third game.

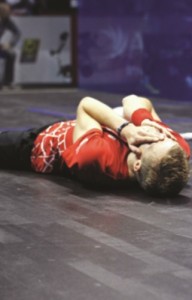

After that, Matthew survived a dangerously inspired fight-back from the brilliant Gaultier, who created sublime touches at the front, elastic changes of direction from the mid-court, and one amazing shot while lying flat on the floor that enabled him to get up and win the rally.

During this phase Gaultier looked very impressive. “I really, really thought I was going to win,” he said. He had reason to. He possessed the more damaging game, he was getting on top and, as he approached parity at the end of the fourth game, he had the momentum with him as well. But Matthew still prevailed.

When he did, his mile-wide smile, outpouring of words, and slumped body showed how thrilled, delighted, and tired he was. “This is the best of all my three world titles—I can’t imagine anything better than this,” he said.

It was all so very different from what took place on the other side of the Atlantic. So how could it have happened?

Matthew had been a subdued and reflective figure after being beaten 4, 5 and 5 in the U.S. Open final. Gaultier illuminated the Drexel University venue with his skill, his grin, and his recently discovered equanimity. The gap between the two players had seemed significant.

But a couple of longer-term factors worked in Matthew’s favor. Knowing he had not competed for a long time before the U.S. Open reduced some of the angst of the heavy loss. He also felt that it might work to his advantage psychologically.

That is because it diverted attention and pressure away from him. “If I had won there (in the U.S.), people would have said I was now the favorite,” he said. “So that helped.”

It helped too that he was better mentally and tactically in Manchester. And that he was given just enough rope to allow these improvements to become important.

It helped too that he was better mentally and tactically in Manchester. And that he was given just enough rope to allow these improvements to become important.

Gaultier’s failure to win either of the first two games was profligate, although he was unlucky that, in both, at game ball his drive darted out of the join between the front and backhand sidewalls and angled towards his body. It cost a penalty point and ended the game each time.

Then, when Gaultier might have pushed through from 9-3 to close out the fourth quickly, his level dropped enough for Matthew to be able to prolong that game. That was crucial.

The Yorkshireman had just enough stamina to carry him to- wards the two-hour mark; the man from Aix-en-Provence did not. Gaultier was already cramping a little before the end of the fourth game. By the middle of the fifth he could no longer run the ball down. It was emotional and physical agony as his dream faded at the final hurdle—for a fourth time.

“I am very, very disappointed,” Gaultier said, his voice issuing from the frontier of despair. Throughout the ceremonies and the interviews his head remained bowed.

Matthew exulted in the applause. “I never thought that I would hear an English crowd as partisan as a French crowd, but they were tonight,” he enthused. “They really pulled me along, didn’t they? I dread to think of the place Greg must be in. I feel for him. But for me—I can’t think of anything better than this.”

But the Englishman had been in a different place from the Frenchman throughout the tournament. As a result the two men reached the final with differing amounts of fuel in the tank.

Gaultier played each of his first four matches last thing in the evening. By the time he had warmed down, showered, eaten, and relaxed it was at least 3:00 am before he got to sleep.

After his quarterfinal he had to do a drug test following the match, and, reportedly, Gaultier needed a long time before being able to provide the necessary. That night—before a semifinal with Mohamed Elshorbagy that lasted eighty minutes—he did not climb in bed until 5:00 am.

By contrast, Matthew’s semifinal lasted a mere twenty-five minutes. This was all that Ramy Ashour’s troublesome calf could withstand before the defending champion had to call it a day. He also said goodbye to his world title and to an unbeaten run of forty-nine matches and eighteen months.

The sport’s most brilliant player and most charismatic personality was reduced to a somber figure, close to tears, at being thwarted in his attempt to repeat his world title triumph in Manchester five years ago when he first became champion.

Ashour bared his soul about how he overcame “a lot of negative energy around me” in his home city of Cairo, where he passed through multiple security checks with nearby tanks each time he practiced. He had, he said, been struggling against “corrupted negative souls who were trying to bring me down.”

However, it was not them but his own body that downed him. For the third time in four world championships he had had to stop in the middle of the tournament.

This time was all the more stunning because Ashour had been transforming his fitness and career with the help of the Aspire center in Doha. But from the moment he pulled a calf muscle during a hard four-game encounter with Cameron Pilley he had been expecting the worst. And two points into the third game against Matthew it happened.

“I’ve been having a lot of physio, and ice and acupuncture— and taking pills to relax,” Ashour said. “I’ve been trying to stay positive but it’s a very big disappointment to me. Now I have to go back and see what’s wrong with my legs.”

Ashour was told he has fatigue in his hamstrings and that the injury is likely to come back. “But I might get lucky if it doesn’t come back,” he added, implying that the calf problem was a compensatory injury.

“It’s all a bit uncertain. I will have to go away for the twenty- fifth time and try to find a way to come back again.” No player will be missed as much as the remarkable Ashour.

A premature exit had also been thrust upon James Willstrop, the former world number one, the previous night. The English- man had been trying to become a father and a world champion simultaneously. It had almost looked possible despite his harassed efforts to drive seventy miles each day to be with Vanessa Atkinson, the former world champion from The Netherlands, whose baby boy was several days overdue.

“There is a philosophy for normal and a philosophy for this week,” Willstrop volunteered. “My girlfriend is expecting, and I am racing backwards and forwards from here to Harrogate (in Yorkshire). “She’s doing fine, but my perspective is slightly skewed at the moment.”

The third-seeded home hope had nevertheless remained cool and efficient until he came up against Elshorbagy, the young sixth seeded Egyptian who upset him in last year’s World Championships, and who upset him again, by 12-10, 11-6, 2-11, 11-6.

Elshorbagy, who has spent seven years in education in England, contained and counter-attacked excellently and afterwards knew how to get the locals on his side. “I just want to congratulate James on playing as well as he did,” he told the crowd.

“He had so much going on in his head. He will be having a baby in a few days time. Going backwards and forwards between Harrogate and here each day—no-one can do that.”

In fact the baby was born the following day, making one wonder how much of a coincidence that was. Elshorbagy was, meanwhile, finding Gaultier just a little too good, and lost in four games.

Earlier another squash legend was in terminal difficulties against Matthew. The Yorkshireman won in straight games against Amr Shabana, who was competing for the first time in seven months following a liver ailment that kept him bed-bound for five weeks.

Earlier another squash legend was in terminal difficulties against Matthew. The Yorkshireman won in straight games against Amr Shabana, who was competing for the first time in seven months following a liver ailment that kept him bed-bound for five weeks.

The four-time former world champion from Egypt then raised a few eyebrows by announcing that he would seek a fifth world title and the accolade of the oldest winner of the World Championships. By this time next year Shabana will be thirty-five.

Other surprises included the defeat of another former world number one from Egypt, Karim Darwish, who failed to make the quarterfinals. He was beaten by Daryl Selby, a member of England’s world title winning team, who had never previously progressed as far.

When Saurav Ghosal also reached the last eight he became the first Indian to get that far. With Dipika Pallikal having made the top ten in the women’s rankings, hopeful pronouncements about a squash take-off in the world’s second largest democracy were increasingly heard.

It was timely that this was one of the great World Championships. More words and more images were cast further and wider than ever, thanks to a deal with the BBC which broadcast live on its website from the quarterfinals onwards and via a red button on one of its TV channels—and created a highlights package as well. The images, thanks to the wonders of HD technology, were also better than ever before.

It was a pity that the women were not part of it, as they had been at the last World Championships in Manchester, five years ago, and in Rotterdam in 2011. Their absence had an element of mystery about it since sources from within the women’s game suggest they had wanted to be part of it.

Moreover, the substantial funding from UK Sport had apparently been forthcoming because the tournament was a preview for squash at the 2014 Commonwealth Games (in Glasgow). And that is an event for which gender equality is fundamental. Worse still, the prospects of a World Open in 2013 now seem—at the time of writing, at least—increasingly remote.

All the more unfortunate, therefore, that the World Championships in Manchester came immediately after a U.S. Open that is the first squash tournament in the world to offer equal prize money.

It was with tennis too, but it was thirty years before Wimbledon followed its example. Squash needs to build much more quickly on the achievement.