By James Zug

In the fall of 1973 the first commercial squash club opened in the United States. Today, public clubs are commonplace. U.S. Squash estimates that a third of all courts in the country are in public clubs. One health club chain, Life Time Fit- ness, has forty-four clubs with squash courts across the country. There are urban veterans like the Bay Club in San Francisco and urban upstarts like T Squash in Cincinnati. There are small key clubs like Potomac Squash outside Washington, medium- sized clubs like Concord Acton outside Boston and the double-digit court behemoths like Meadow Mill in Baltimore and Fairmount Athletic outside Philadelphia. Forty years ago, it was zero percent.

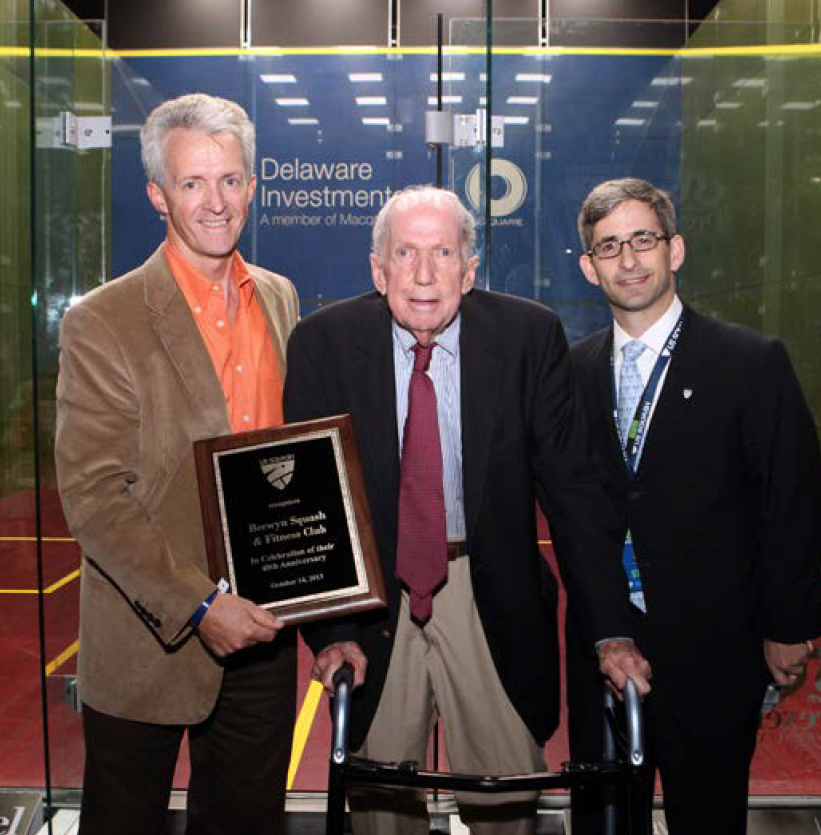

Ironically, Berwyn Squash & Fitness Club was the nation’s first public club, and through turmoil, bankruptcy, excitement, friendship and a leaky roof, it has survived to celebrate its fortieth anniversary.

Berwyn is in the Main Line, the western suburbs of Philadelphia where many towns are named after Welsh villages (Ardmore, Bala Cynwyd, Malvern, Radnor) because they were originally settled by Welsh Quakers. Berwyn means white head in Welsh: barr “head” and wyn “white.” If there is one thing that Berwyn Squash has caused its owners for the past forty years is some grey hair.

Paul Monaghan was behind a couple of radical innovations in squash. He designed the first squash courts with modular walls (at Hill School; now standard), the first courts with a panel for photographers and balconied galleries (at Penn; now often standard) and the first full-length glass back wall (also at Penn; now standard). In the early seventies Monaghan decided architecture and design weren’t enough. “I saw the boom all around me for indoor tennis facilities,” Monaghan, 85 years old now, told me this summer. “I thought that maybe this could work for squash. It was a concept and we thought, ‘Why can’t we do this?’”

Monaghan formed a partnership with Barclay White. A local real estate developer, White worked for the family firm his father founded in 1913 (they built Skytop Lodge in the Poconos, as well as many schools, hospitals and corporate buildings). He also passionately loved doubles and had built a court in a barn on his property—he called it the South Penn Wood SRA. (White died last December at the age of ninety.)

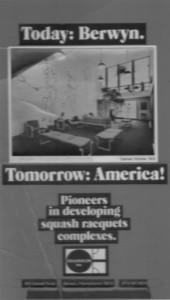

They formed a company called Squashcon. Although they chose the name at random, it did suggest the phrase Squash Convention (the original Comic-Con was founded in 1970). With White handling the financing and Monaghan handling the designing, the team went out and looked for a location. They found a 4.5-acre site under some high power lines in Berwyn. PECO, the electric company, was happy to rent the property and offered an inexpensive lease. The site was considered a good location, as it was near the Route 202 Great Valley Corridor, a region of burgeoning corporate headquarters. Monaghan designed and built a low-cost, industrial-looking structure.

They formed a company called Squashcon. Although they chose the name at random, it did suggest the phrase Squash Convention (the original Comic-Con was founded in 1970). With White handling the financing and Monaghan handling the designing, the team went out and looked for a location. They found a 4.5-acre site under some high power lines in Berwyn. PECO, the electric company, was happy to rent the property and offered an inexpensive lease. The site was considered a good location, as it was near the Route 202 Great Valley Corridor, a region of burgeoning corporate headquarters. Monaghan designed and built a low-cost, industrial-looking structure.

It had four hardball singles and two doubles courts. The original design had just one doubles court. White suggested they put in the second. “It was a mistake,” Monaghan said. “We had so many people new to squash and racquet sports in general—doubles was more than they could handle. The court sat empty for much of the time.” The biggest innovation about Berwyn was that it had air-conditioning. In 1973 only a handful of clubs had AC; with the hardball, squash was simply a no-go from April to October. But a commercial club couldn’t afford to be empty for six months a year. In his one extravagant gesture, Monaghan commissioned a local artist to make a mural for the main wall in the club’s foyer. The tripartite mural was modeled after the Frank Mullins’ illustrations in Al Molloy’s 1963 Sports Illustrated Book of Squash, which in turn were modeled on Molloy himself.

No one can remember the exact day the club opened. More than one person recalled seeing Monaghan sweeping leaves off the driveway on the opening day. (”It was an all-hands-on-deck operation,” said Alec Monaghan, Paul’s son.) Monaghan held a press conference that a half dozen journalists attended and the adventure began.

Berwyn immediately became popular. Members of private clubs joined because of its convenience and its relaxed social scene. Additionally, a lot of people who had never heard of the game, and people who were not the type to populate an exclusive private club, joined. “I was proud that I got the ordinary man into the club,” Monaghan said.

A burgeoning scene developed. Al Molloy came out of Penn to coach in the off- season; he ran a Friday night couples doubles clinic that was very popular: Sharon and Bill Schwarze played in it, as did Judy and Rick Owens (who was drafted by the Oakland Raiders after a football career at Penn). Sheila Molloy, Al’s wife, ran a women’s morning round-robin. Cathy Rush (a basketball coach who was later immortalized in the 2009 film The Mighty Macs) played in that. Jack Bogle, the founder of nearby Vanguard Group, was a regular player. He often sparred with some of his employees at lunch time and had one of his heart attacks on court there in 1980. Richie Ashburn came around. People sat in the foyer and drank beer. Usually people went out afterwards to restaurants in Devon or Wayne. Some Saturday mornings it smelled like a fraternity.

Seeking members, Monaghan visited the various office buildings in Great Valley and spoke to employees and left flyers about the club. “I was working for a real estate company in the early seventies,” said Mark Werther. “The club sent a representative to offer new memberships. It was great as it was easily affordable and close by for me. I took a look and joined. I had been playing in some weird places, courts that were always about ninety degrees. You would end up chasing the ball around the court. Or courts that were so cold some days the ball would not come off the front wall. So joining a new club with ideal conditions was a pleasure.”

Seeking members, Monaghan visited the various office buildings in Great Valley and spoke to employees and left flyers about the club. “I was working for a real estate company in the early seventies,” said Mark Werther. “The club sent a representative to offer new memberships. It was great as it was easily affordable and close by for me. I took a look and joined. I had been playing in some weird places, courts that were always about ninety degrees. You would end up chasing the ball around the court. Or courts that were so cold some days the ball would not come off the front wall. So joining a new club with ideal conditions was a pleasure.”

“I offered a ‘six for sixty’—six lessons for $60,” said George Kalman, an early pro at the club. “There were a few juniors but mostly adults. The beauty of Berwyn was the scene. There might be a vice president of Sunoco Oil sitting next to a mailman. Squash is the big equalizer. The social scene never overshadowed the squash, but there was a lot of socializing. You didn’t have a board of directors controlling the atmosphere; the members built the atmosphere. It was organic. I had a key to the club and once, very late at night, I was driving past and had to go to the bathroom. So I drove in, parked, opened the door and turned on some lights. One of the members was asleep on the couch. His wife had kicked him out of the house.”

Berwyn became a hotbed of play. The club fielded many teams in the Philadelphia SRA singles and doubles leagues. They hosted a pro hardball singles event (a check for Sharif Khan, the winner of the tournament, notoriously bounced). They had the Liberty Bell, Berwyn Weekend and the Berwyn Junior Classic, eventually a core of seven annual tournaments. In addition, they hosted a slew of Philadelphia SRA events (including mixed doubles events like the Merry Mixed) and national ones: they hosted the U.S. Mixed in 1983 (sponsored by Bloomingdales), 1984 and 1992, and the women’s nationals in 1985. A lot of top juniors and adults floated through, giving $5 lessons as much as receiving them. Tom Page coached the women’s C league team. After he broke his wrist, he played left-handed in a club B tournament and lost in the finals. Berwyn was the training ground for two generations of junior stars who went on to college careers: like the Ball brothers, Russ and Andy; the White brothers, Bob and David; Peggy Reed Brehman, Sara and Scott Hammond. The club also was an early proponent of the 70+ ball—the first step away from the old bullet-fast hardball of yesteryear.

Glowing with success at Berwyn, Squashcon opened a second facility in 1974 in a beer distributor’s warehouse in Manayunk, a working-class neighborhood along the Schuylkill River in western Philadelphia. They installed seven courts (one was Monaghan’s famous collapsible folding court). “In 1977 I witnessed a phenomenal match at the courts in Manayunk between Tom Page and Hashim Kahn,” said longtime Berwyn member Dick Cohen. “It was a close match. Hashim would strike the ball and then briskly walk over to where Page would have to return it. Page won but the great applause was for Hashim.”

In 1976 they added a third, four-court club on the thirteenth floor of an Art Deco office building on the west side of Washington Square in downtown Philadelphia. They also looked hard at a location in Plymouth Meeting, PA. In addition, Monaghan met with people in Hartford and Boston about setting up potential Squashcon franchises. “They wanted to know what we were putting in besides our ideas,” Monaghan said.

It was a classic case of overreaching. Berwyn was cash-positive but still struggled, before computers, to bill properly. It was a pay-per-play club: you could walk in, put down a couple of bucks and get on court. For those who had annual memberships, some wouldn’t renew but still came by. A lot of cash floated around and sometimes it went missing. “We hired young, attractive people for the cash register,” said Monaghan, “and usually they weren’t too smart or equipped with much business experience.”

“As a public club, the accounts were set up to pay-as-you-go and people were forever running in late and ‘paying later’ and then slipping out still without paying, so we had more accounts receivable than we should have,” recalled Sharon Schwarze, a longtime member and manager. “Later when we tried to collect (we did have very good re- cords), they, of course, couldn’t remember.” As it was a public club, sometimes people with less than noble impulses hung around. One person purloined a tree-like plant from the lobby. Another was caught driving away with two bales of fresh towels.

Moreover, the Manayunk facility was in a rough neighborhood. “Today it would be great,” said David Page, who was a teaching pro and manager for Squashcon from 1975 to 1979. “Today Manayunk has completely gentrified. But we were about fifteen years too early. You just couldn’t keep people there after 7pm. It was a miscalculation. We never got cash positive there. Washington Square cash-flowed immediately, but it was expensive and we failed to get a liquor li- cense which was a critical issue.”

In the early 1980s, Squashcon ran out of money, missing a couple of payments. Manayunk became a warehouse again; Washington Square was converted into law offices. Berwyn got sold to members.

“It is a great story,” Page said. “What Paul did was very adventurous, but the truth of the matter is that we should have sorted it out in a better way in a commercial sense, especially food and a bar. Paul made a great effort at something pretty neat and noble, but it was fraught with challenge. In the end, with Manayunk a bit of an albatross, there were too many things going against Squashcon.”

A group of members bought Berwyn from Monaghan and White. Monaghan was so burned out by the whole mess—the time and effort he put in, the money lost— that he left the squash business scene and joined Cushman & Wakefield, the real estate firm. He went on to a successful career, although he continued to play in doubles tournaments.

The new ownership group included Gerry Bricks, Jim Egan, Jack Foley, Ted Hill, Bob Shenkin, Bill Schwarze, Fred Wallace and Dick Will. Later Joyce Davenport and Rick LeFevre joined. Dick Will chaired the group and encouraged a renaming of the club, Berwyn Squash & Nautilus Club.

As time progressed, problems revealed themselves to the new owners. Monaghan and White had not invested enough in the original building. The flat roof leaked and partially collapsed once after some heavier air-conditioning units were installed. “This is just not the climate for a flat roof,” said George Kalman. “The roof tiling would get saturated and a tile would fall off.”

“I was continually looking for ways to trap and divert water that inevitably leaked through the flat roof,” said Joyce Davenport. There was no insulation in the walls. The club’s original air-conditioning and heating system wasn’t strong enough to work well without insulation, especially with plywood walls. The club put in kerosene heaters. “The courts were still cold in the winter,” remembered Sharon Schwarze, Bill’s wife and a longtime leader at Berwyn. “The plywood delaminated and had to be repaired frequently. The old hard ball was very hard on it, especially the hard serve and the boast. We filled and painted many times. We had to put grit in the floor paint so people wouldn’t slide but pity the person who fell (especially right after painting) and shoe soles deteriorated quickly.”

It was a fly-by-night operation in a way. There was no photocopier at the club, so they used members’ offices to print up bills or tournament entry forms. It was so cold some winters that players warmed up in the sauna. “The extremely frigid, rattling and echoing hardball courts and the smell of the kerosene heater and the 1970s-vintage orange lounge chairs—that is what I remember,” said Dave McNeely, the 1999 national champion, who started playing there in the late 1980s. “You could see your breath on court. But Berwyn was not that dissimiliar to the international model in that it made squash accessible to all, and there was always a cold beer and good conversation waiting after your match.”

Even a very scattered, partial list of employees at Berwyn is long: John Havens, Tom Page, Bill Bowman, Nancy DeAngelis, Phil Decola, Ray Weiglein, Hugh Peck, Jim Masland, Ron Koenig and Bill Ramsay. In 1981 Satinder Bajwa was visiting his brother, an optician, who lived in Philadelphia. Bajwa, 22, had just left a job as an aeronautical engineer with British Airways. He looked up squash courts, called up and scheduled a game. It turned out it was with one of the owners. “We played and I barely won. I told him, ‘Next time I’ll bring a proper ball, this one we used today was an odd one, it whizzed too fast. The court, well, there is nothing I can do about your court.’ I didn’t know anything about hardball. The next thing I knew we were talking about whether I wanted to work there part-time.” Bajwa spent eight months at Berwyn, his first squash job that put him onto the path of working with Jansher Khan and coach- ing at Harvard.

The one name synonymous with Berwyn has been Joyce Davenport. She began teaching part-time at Berwyn in 1977 while a second-year law student at Villanova. After a couple of short-term managers, the owners asked her to step in. “I was be- tween jobs,” she said, “and thought this might be a nice interlude. Well it extended from 1981 until 1996.” She gave lessons, strung racquets, cleaned the courts and started or ran a dozen tournaments a year.

How many people does it take to change a light bulb at Berwyn? Just one, if you have Davenport. “She learned to climb the A-frame ladder to the top of the doubles court to change light bulbs,” remembered Sharon Schwarze. “Twenty-something young men were afraid, so for many years she did it herself. I could hardly watch. The A-frame had to be wrestled over the balcony of the doubles courts and then the center hoisted to the ceiling (so one climbed straight up). She straddled the center ladder and then reached down for the twelve-foot long fluorescent light bulbs.”

“Joyce Davenport really taught me how to swing a racquet, particularly my back hand,” Dave McNeely said. “Those days were great. She has such a graceful swing and one of the best backhand three-wall boasts ever. On snow days, I would hang around the courts and hit all that I could and help her do membership mailings, string racquets and whatever else there was to do. Joyce was a key component to making hardball interesting and exciting during that era.”

“I was so excited when we first hosted the U.S. Mixed,” said Davenport, now a member of the U.S. Hall of Fame, “that I decided to clean every inch of the painted floors—removing shoe marks, stains, etc. I thought I had done a perfect job but noticed the players were sliding all over the court Friday night. I had used Softscrub and inadvertently created a skating rink. I stayed well past midnight removing the residual powder until many hours later it was truly perfect.”

Another member, Peter Hausmann, eventually took over Berwyn. Hausmann grew up in northern New Jersey. He played some squash at Hamilton College and took a job a mile away from the new Berwyn Squash Racquets Club. He happened to come by on the opening day and has been a member ever since.

In the late 1980s he bought the club. The owners group was personally liable and deeply in debt—something around $1.4 million. They couldn’t afford to maintain the club and pay down the debt. The bank, at the same time, had written the debt off, and when Hausmann asked them for the club, they gave it to him for free as a condition for another real estate deal he was doing. “The bank thought I was crazy, buying it. Anyway, I said to the group: ‘Give me the club and leave $10,000 in the bank and I’ll give you all a life membership in the club.’” Hausmann didn’t buy it as an investment. “I didn’t expect to make money, but I thought it could be continued. There are thousands of people working within a five- mile radius of the club. I said, ‘Let’s market to them.’” He began the process of converting courts to softball, did a number of renovations and, with Davenport at the helm, the club continued along.

The next leader of Berwyn came out of Canada by way of Bermuda by way of England. Dominic Hughes, fifty-one, grew up in Sheffield playing at Abbeydale, the club that built the first back wall with any glass (Penn’s court was the first full-wall one). When he was eighteen, he moved to Bermuda and worked as a chef at the Hamilton Princess Hotel. After a couple of years, Hughes went back to the UK and then re- turned to Bermuda as the national coach. “I thought I had died and gone to heaven,” he said. “Playing squash in Bermuda. Twist my arm.” After a few more years, he left Bermuda and moved to St. Catherine’s, Cana- da, where he was coaching squash. He also did a stint in Calgary and in Winnipeg.

In October 1996 Peter Hausmann was talking about court renovations with Gordie Anderson who mentioned that Dominic Hughes was looking for a job. Hausmann called Hughes. “I told Peter, ‘This is golden for me,’” Hughes said. “’I know I can make this work.’” A couple of years after Hughes arrived, Hausmann sold him the club after re-negotiating the lease with PECO: “There was no way you could put money into the club without that lease.”

When Hughes arrived, Berwyn had 200 members. Today it has 600 memberships that serve about 1,000 people. In 1997 he and Hausmann added two more singles courts and expanded the fitness room—to- day the club has six softball singles courts. To fill the courts during the mid-afternoon hours, Hughes worked hard to bring in schools. A number of private schools used Berwyn as their home courts, particular Shipley and Agnes Irwins. But the big move was getting the local school district involved. Today the elementary, middle and high schools (Conestoga) in the district all have teams at Berwyn. I have never been to Berwyn in recent years without seeing a swarming gaggle of Conestoga kids coming or going or both.

“It comes down to geography and quality and consistency of service,” said Hughes. “We have picked up some business now that there are many many more courts out in the area, but we’ve lost business too. If you have a twenty-minute commute to a club or a thirty-minute commute, you are going to choose the twenty-minute club. Geography—there’s very little you can do about it. But service is key. Care is a four-letter word I want to hear.”

As it heads into its fifth decade, Berwyn is not standing still. In 2010 Hughes installed solar panels on the infamous flat roof (see photo). It was a substantial long- term investment in the club. This spring he filed plans with the township for another expansion. They are hoping to add two more floors of multi-purpose rooms for yoga, spinning and karate and later add three more courts. “I could use the courts right now,” he said. “Squash is the heart and soul of the club. But for the long-term security of the club we need to diversify. You always have to look down the road.” It is now Berwyn Squash & Fitness Club.

As it heads into its fifth decade, Berwyn is not standing still. In 2010 Hughes installed solar panels on the infamous flat roof (see photo). It was a substantial long- term investment in the club. This spring he filed plans with the township for another expansion. They are hoping to add two more floors of multi-purpose rooms for yoga, spinning and karate and later add three more courts. “I could use the courts right now,” he said. “Squash is the heart and soul of the club. But for the long-term security of the club we need to diversify. You always have to look down the road.” It is now Berwyn Squash & Fitness Club.

And so the original experiment with public squash continues. With luck: the PECO lease is key. With location: the Route 202 corridor has grown tremendously. And with loyalty: each public club has some core reason for its survival and no doubt for Berwyn it has been the forty years of loyal support from its members.