By Paul Assaiante, Trinity College Head Coach and Head National Coach

Too many people simply go from lesson to lesson and think that that is the panacea for developing a squash game. Or on the flip side of the coin, play “friendly game after friendly game” in the belief that that is what is needed for improvement.

While both are important to the road to growth, drilling is a critical component in a players’ development.

Remember that practice does not make perfect, but perfect practice makes perfect. There are essentially two types of drilling—partner and solo. It is the latter that I would like to discuss.

This summer, while at the world championships in Mulhouse, France, I spent the entire day watching the players; not watching their matches, but watching their practice! It was unbelievably instructional. To see James Willstrop solo practice was AWESOME!

There are many different drills one can do, but here are the few that I would suggest starting off with.

Warm up with the classic figure four drill. Stand near the ‘T’ and hit crosscourt forehand-front-side, and then with the back- hand hit crosscourt front-side. This creates a nice rhythmic way of hitting and gives you much better racquet control. A goal of 100 in a row is a good one, and while you will find it challenging at first, you will improve rapidly.

Secondly, stand on or in front of the red line facing the side wall. Hit consecutive volleys along the wall. First forehand, then backhand—twenty-five in a row as rapidly as you can. When doing this, it will look very much like the classic down the line volley return of serve. This will improve your racquet work and also strengthen your forearm.

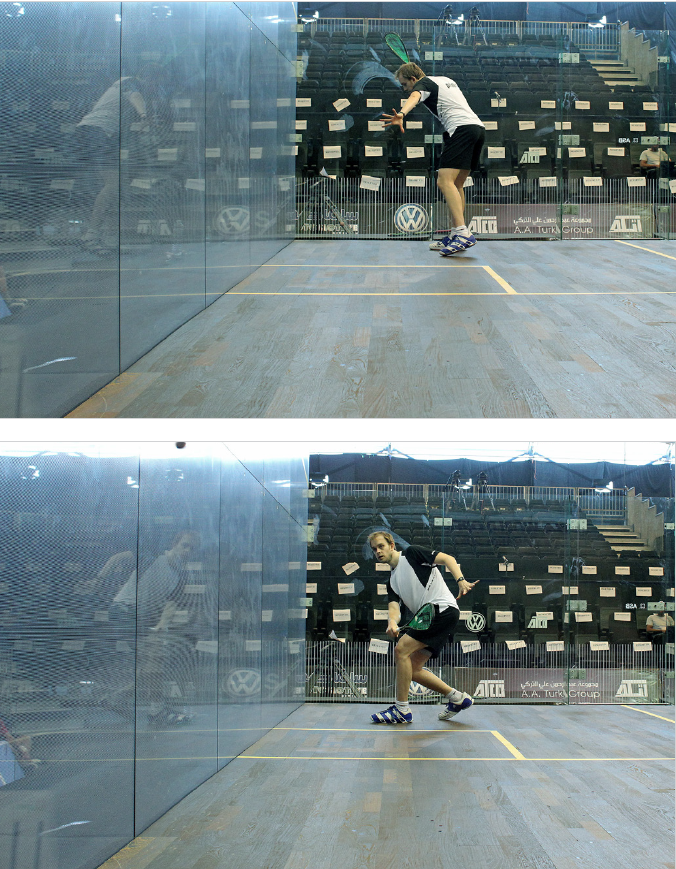

One thing I learned in watching Willstrop solo is that one really needs to focus on having a ball die in one of the four corners. When you rally in solo work, it means that the ball still has “air in it” so to speak. In other words you would need to be hitting a less-than-perfect shot to rally with it or else hit it after a second bounce. What Willstrop does is simply hit a weak drive, either straight or crosscourt, that ends up in the mid court. From there he takes his space, gets down low and hits a perfect dying length into either corner. He then jogs back and retrieves the ball, flicks it to the front wall and does the same thing to the other side. He is able to find the perfect dying length off of both the backhand and forehand and then later, when he plays his match, his length is immaculate.

He also does this with his drop shots and, as a result, he can play the ball to space to the four corners of the court so that they truly die in the intended area. When he plays, he now has the muscle memory ingrained so that he owns it.

It was interesting sitting next to Chris Gordon at the worlds, a man who is around 40 in the world and watching Willstrop play. While everyone was ooohing and ahhhing about his nicks and deception, Gordon turned to me and said in wonderment, “man his length is perfect.”

This doesn’t happen by accident.

If you want to make that jump—that will allow you to beat an- other player—learn to get the most out of being on court…alone.