By James Zug

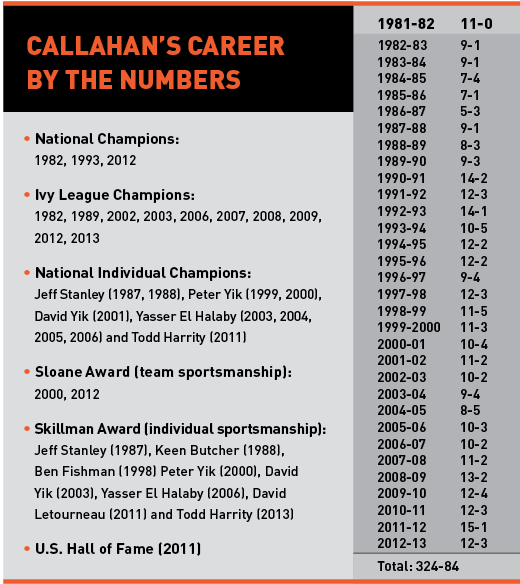

It was never supposed to work out like this. In the summer of 1981, Princeton’s athletic director asked Bob Callahan, newly-married IBM salesman, to be on a search committee to find a new coach for the Princeton University men’s squash team. He was a recent alum, former captain and lived nearby. He never thought about the job for himself. He had been accepted at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. The plan was Wharton and then back to IBM. A friend suggested that maybe he consider the job. He did. He took it.

Even then, it wasn’t for good. He negotiated an agreement with IBM that he’d do the Princeton job for three years, taking some economics courses at the university, and then return in 1984; this was pretty unusual, but Steve Vehslage, a Princeton squash alum and IBM executive, helped arrange it. “I had no goal of being a squash coach in general,” Callahan said. “It was more I wanted to come back and coach at my alma mater and do what I had loved as an undergraduate.”

After three years, his hiatus was over. A friend asked him a simple question: “On Sunday nights, do you get nervous about the week ahead?” While at IBM, Callahan suffered those anxiety-ridden, sleepless nights, churning through what he had waiting for him the next morning. At Princeton, he couldn’t wait for Monday to come, for another week to get going. He thanked Vehslage and decided to stay at Princeton. The three-year sabbatical became thirty-two years.

The Master of Jadwin Gym C-Floor has a life outside squash. His religious faith is quiet but deeply abiding—many of his players don’t even know which church in Princeton he attends, but only that he attends each Sunday—and his greatest love is not squash but his family. He and his wife Kristen have five sons: Greg, Tim, Scott, Matt and Peter. All five went to Princeton. All five played on the squash team. Against Yale in 2006, Tim at No. 9 won a key match in overtime in the fifth game. Kristen teaches computer and economics courses at Mercer County Community College. They are close-knit.

Callahan is an illustrious conversationalist. He is always a bit late because he is talking with someone. “He’s got ten things to go through and has only gotten through five,” Gail Ramsay, the Princeton women’s coach, said about their regular meetings. “He doesn’t rush out of the office. He gets derailed by another conversation.” He is detail-orientated but disorganized. He wants to cover a thousand things and often the preamble to each practice takes a long time, players itching to get on court; at one point his captains put a time limit on his pre-practice homilies. He has an encyclopedic memory. He can remember every point he has seen, who was down 2-0 and 8-2 in the third like it was yesterday not a quarter century ago. At introductions before matches, he stem-winds about each player. My calls with him each spring to discuss the season bleed over into a second hour and then into a third. In that regard, he is a bit like Jack Barnaby, the old Harvard cynosure, someone who is tremendously passionate about the game.

Callahan is an illustrious conversationalist. He is always a bit late because he is talking with someone. “He’s got ten things to go through and has only gotten through five,” Gail Ramsay, the Princeton women’s coach, said about their regular meetings. “He doesn’t rush out of the office. He gets derailed by another conversation.” He is detail-orientated but disorganized. He wants to cover a thousand things and often the preamble to each practice takes a long time, players itching to get on court; at one point his captains put a time limit on his pre-practice homilies. He has an encyclopedic memory. He can remember every point he has seen, who was down 2-0 and 8-2 in the third like it was yesterday not a quarter century ago. At introductions before matches, he stem-winds about each player. My calls with him each spring to discuss the season bleed over into a second hour and then into a third. In that regard, he is a bit like Jack Barnaby, the old Harvard cynosure, someone who is tremendously passionate about the game.

Each week at his summer camps, the night the parents came and took away the campers, the counselors would have a late dinner. Callahan would rehash the last week and plan the next week, and these discussions would last well after midnight, with the next campers arriving at seven in the morning. On road trips, he would stay up until two in the morning, looking at video, pondering tactics, remembering old matches, examining footwork patterns—the classic hotel room colloquy. “I used to come home exhausted from a trip,” said Neil Pomphrey, the Princeton men’s assistant coach, “not because of the driving or matches but because Bob would want to stay up late talking.”

He had fun with his players. I remember at camp in 1983 he did a tiny little jig with a smile when we were all hanging around the quad with “Billie Jean” blasting from a boom box. He was a father-figure, but approachable; he had passion and compassion. “Bob is outwardly calm,” said Pomphrey. “But he loves his players. We had some wonderfully special team meetings after matches we lost. He would get very emotional expressing how proud he was.” He gave them latitude to select captains. He would meet with his captains for breakfast every Monday morning to collaborate about the week ahead. Annually, he and Kristen hosted a barbecue at their home at the beginning of the season and at the end of the season, as well as a Sunday brunch during commencement weekend for the seniors and their families. At the opening bbq, he would deadpan and pretend not to know the freshmen’s backstories. At his summer camp he invented long, mostly false stories about players who were giving exhibitions.

He had fun with his players. I remember at camp in 1983 he did a tiny little jig with a smile when we were all hanging around the quad with “Billie Jean” blasting from a boom box. He was a father-figure, but approachable; he had passion and compassion. “Bob is outwardly calm,” said Pomphrey. “But he loves his players. We had some wonderfully special team meetings after matches we lost. He would get very emotional expressing how proud he was.” He gave them latitude to select captains. He would meet with his captains for breakfast every Monday morning to collaborate about the week ahead. Annually, he and Kristen hosted a barbecue at their home at the beginning of the season and at the end of the season, as well as a Sunday brunch during commencement weekend for the seniors and their families. At the opening bbq, he would deadpan and pretend not to know the freshmen’s backstories. At his summer camp he invented long, mostly false stories about players who were giving exhibitions.

Character not talent mattered to him. Princeton has won more Skillman Awards for individual sportsmanship than any other college. “I used to get mad at myself when I wasn’t performing well,” said Keen Butcher, who won the Skillman his senior year at Princeton. “Bob said to me, ‘Don’t beat yourself. Your opponent is trying to do that already. Be your best friend out there.’ He taught me how to be happier on the court, how to get my mind in the right frame of reference. It made me a better sport, but it also made me a much better player.”

Callahan is connected to a vast network of former players and parents and friends. He finds people jobs. He advises. As coach, he regularly hosted on-campus receptions and dinners with parents and alums—at one each winter the juniors got up and spoke about the seniors. Along with Ramsay, he ran three massive alumni reunions for the Princeton program, one every five years. He sent out newsletters the night after each match to a list of hundreds of alums. He personally knows every Princeton squash player of the past forty years. He gets invited to countless weddings. He inspires great loyalty: former player Dent Wilkins has worked at 43 weeks of Princeton Squash Camp.

Callahan is connected to a vast network of former players and parents and friends. He finds people jobs. He advises. As coach, he regularly hosted on-campus receptions and dinners with parents and alums—at one each winter the juniors got up and spoke about the seniors. Along with Ramsay, he ran three massive alumni reunions for the Princeton program, one every five years. He sent out newsletters the night after each match to a list of hundreds of alums. He personally knows every Princeton squash player of the past forty years. He gets invited to countless weddings. He inspires great loyalty: former player Dent Wilkins has worked at 43 weeks of Princeton Squash Camp.

He knew how to inspire his players. When Keen Butcher told him freshman year that he wanted to become a national championship caliber player, Callahan said, “I don’t think you can do that.” A few years later he told Butcher, “I did that on purpose, to motivate you. I knew you could do it, if you wanted it badly.” After losing to Harvard 6-3 in the 1993 regular season, he hinted to his players that if they managed to beat Harvard in the national team tournament, he would shave his head. Playing at home at the national teams, Princeton squeaked by Yale 5-4 in the semis; in the other match Harvard slipped past Western Ontario 5-4. In the finals, with Jon Karlen out, Harvard was weakened just enough for the Tigers to pounce. With the match knotted at 4-4, Alec Decker overcame Josh Horwitz at No. 3 to clinch Callahan’s second national title. Celebrating afterwards, Callahan had to slip away from the upperclassman who were rumbling about the head shaving. To compensate, they shaved the heads of the freshman on the team. No one said a word about shaving Callahan’s trademark moustache.

There was a reason for everything. He would put the hot-shot recruit on the court with his top veteran first thing in September. He was a soft recruiter, usually no hard-sell, but fought for players if they wanted to come. He was supremely generous. If a player wanted to apply to Princeton but wouldn’t get in, he would often call rival coaches with the tip.

There was a reason for everything. He would put the hot-shot recruit on the court with his top veteran first thing in September. He was a soft recruiter, usually no hard-sell, but fought for players if they wanted to come. He was supremely generous. If a player wanted to apply to Princeton but wouldn’t get in, he would often call rival coaches with the tip.

Intensely curious, he liked working on technique, movement, strategy. He maintained an emphasis on drilling. He was precise on court, drilling one particular thing— keeping it simple. He was always taking notes, scribbling on scraps of paper, writing down things he wanted to say to a player in between games or at a later practice. “When I was at Princeton, Bob was willing to correct what was wrong and not coach a player how to play with a weakness,” said Jeff Stanley, his first great player. “As with most sports, it was often one step back to go two steps forward. Bob was willing to risk going backwards to ensure the success down the road.”

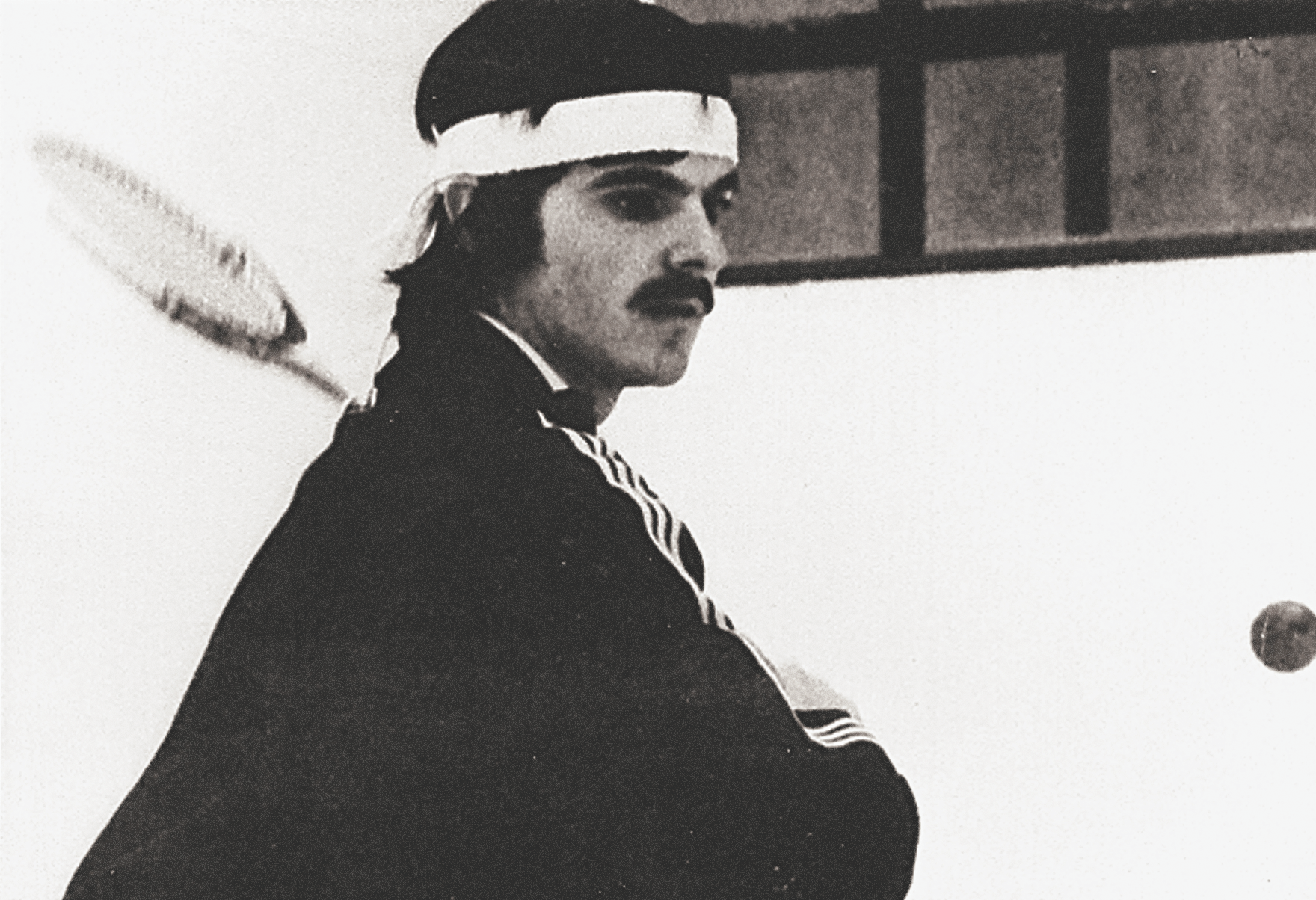

He was a good player himself. Before his hips went wobbly (he had one hip replaced in 2002 and until recently had been pondering the other), he got on court all the time. He won the U.S. 30+ in 1989. Some years, he and Gail Ramsay partnered in the U.S. Mixed Doubles. Callahan’s game was like his personality: deliberate, disciplined and well-thought-out. He was conservative. “You should lock that in,” he would say, again and again, whenever anyone was discussing a wavering relationship with a girlfriend or a job prospect or a bread-and-butter shot. He could always hit pure, straight rails, and he taught the game that way: “He always felt that if you could hit tight, deep rails, it would open up the court,” said Pomphrey. “His idea was, ‘Let’s hit five rails in a row, let’s hit six in a row. Let’s hit the sixth.’”

In person you might notice a slight nod and pause with Callahan before he answered a question. That nod might have been the conversational equivalent of his famous pre-serve ritual. Jeff Stanley first encountered it during a match against Callahan when he was a junior playing in the New Jersey state championships: “He would rock back and forth, bounce the ball a few times, then gaze up at the front wall, pause for an eternity and then serve the first serve into the ceiling. Then he would repeat with the second serve except now he would hit a perfect lob serve through the rafters. After a few points of this, the ball was cold, he was refreshed and I was out of my mind.”

In person you might notice a slight nod and pause with Callahan before he answered a question. That nod might have been the conversational equivalent of his famous pre-serve ritual. Jeff Stanley first encountered it during a match against Callahan when he was a junior playing in the New Jersey state championships: “He would rock back and forth, bounce the ball a few times, then gaze up at the front wall, pause for an eternity and then serve the first serve into the ceiling. Then he would repeat with the second serve except now he would hit a perfect lob serve through the rafters. After a few points of this, the ball was cold, he was refreshed and I was out of my mind.”

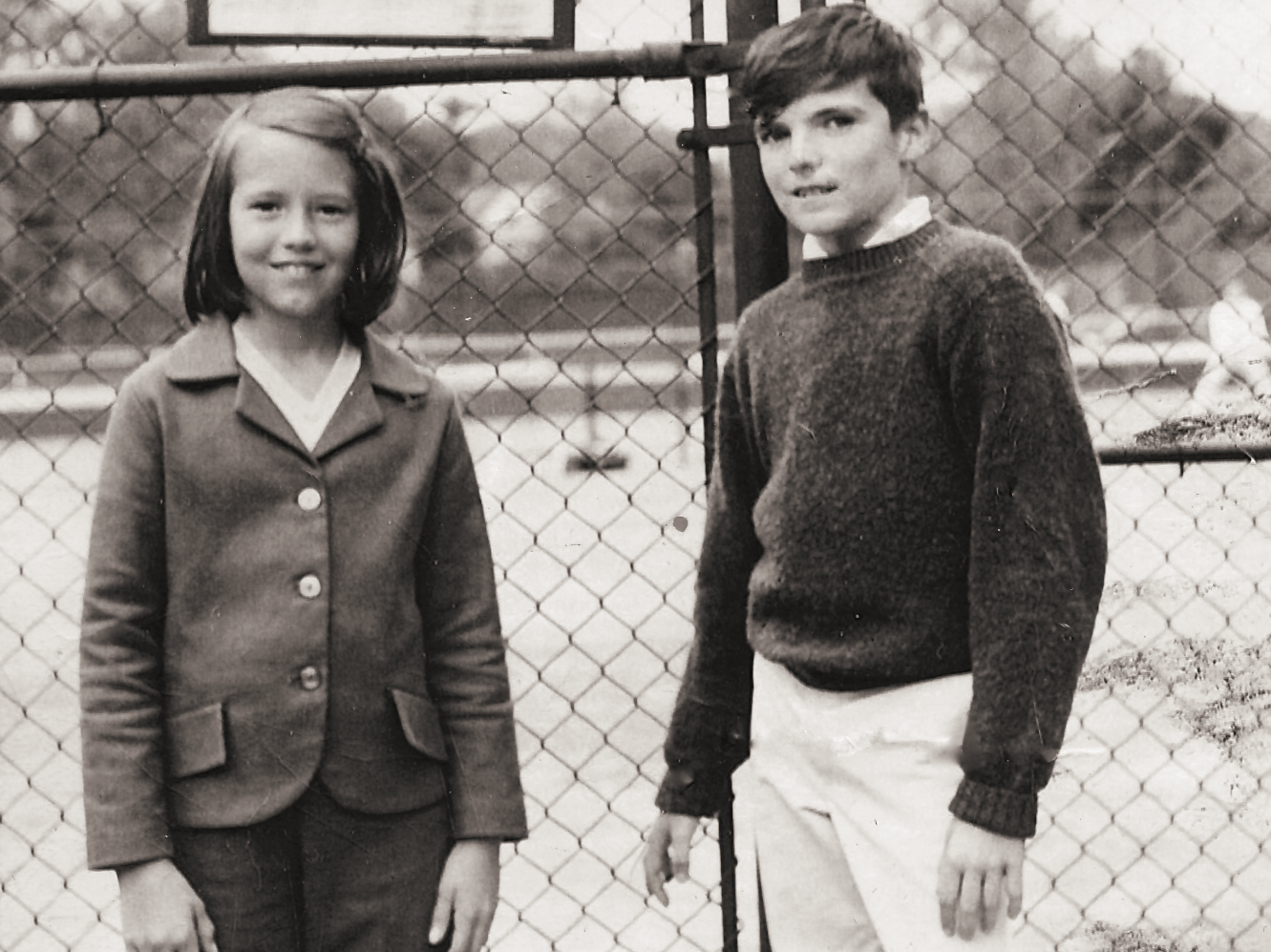

Robert W. Callahan was perhaps the only person who could have led U.S. squash’s softball revolution, since he was the ultimate insider. He grew up on the Main Line outside Philadelphia, three houses down from the Cynwyd Club. He and other kids in the Bala Cynwyd neighborhood spent countless hours there after school, on weekends and during the summer. “We had a racquet gang there,” said Gail Ramsay. “We had the run of the place and would play tennis, squash and just roam around. Bob was always very inclusive, happy to hit with anybody. He was a lot like he is now, sincere and thoughtful and genuine. He doesn’t seem that much different now.”

Tennis was Callahan’s game of choice while a teenager. In 1971 he was the number one ranked player in the Middle States U16s and a year later the No. 3 ranked player in the Middle States U18s. He played number one on Episcopal Academy’s tennis team for the last three years of high school, never losing a match in the Inter-Academic League. In high school he spent his summers teaching tennis: at Belmont Park, a Philadelphia public park; at Camp Tecumseh under Al Molloy; and then at Germantown Cricket Club. In college, after one summer when he and a friend ended up working at a 55-gallon steel drum factory in downtown Philadelphia, he spent three summers running the junior tennis program at Merion Cricket Club.

“Squash was something I did in the winter to stay out of trouble,” said Callahan. Norm Bramall hit with him each winter at Cynwyd, he grabbed a couple of squash lessons at Merion from Jimmy Tully (the source of much of Merion’s mid-century greatness) and Darwin Kingsley gave him some pointers as squash coach at Episcopal Academy. “Not once did I think I could be in squash for a career,” Callahan said. As a senior he played No. 5 on EA’s squash team, the unofficial national high school champions, but was clearly a step below the Page, Bottger, Havens, Swain and Mateer clans that dominated the ladder. (He also played soccer on the league-winning EA team his senior year.)

“Squash was something I did in the winter to stay out of trouble,” said Callahan. Norm Bramall hit with him each winter at Cynwyd, he grabbed a couple of squash lessons at Merion from Jimmy Tully (the source of much of Merion’s mid-century greatness) and Darwin Kingsley gave him some pointers as squash coach at Episcopal Academy. “Not once did I think I could be in squash for a career,” Callahan said. As a senior he played No. 5 on EA’s squash team, the unofficial national high school champions, but was clearly a step below the Page, Bottger, Havens, Swain and Mateer clans that dominated the ladder. (He also played soccer on the league-winning EA team his senior year.)

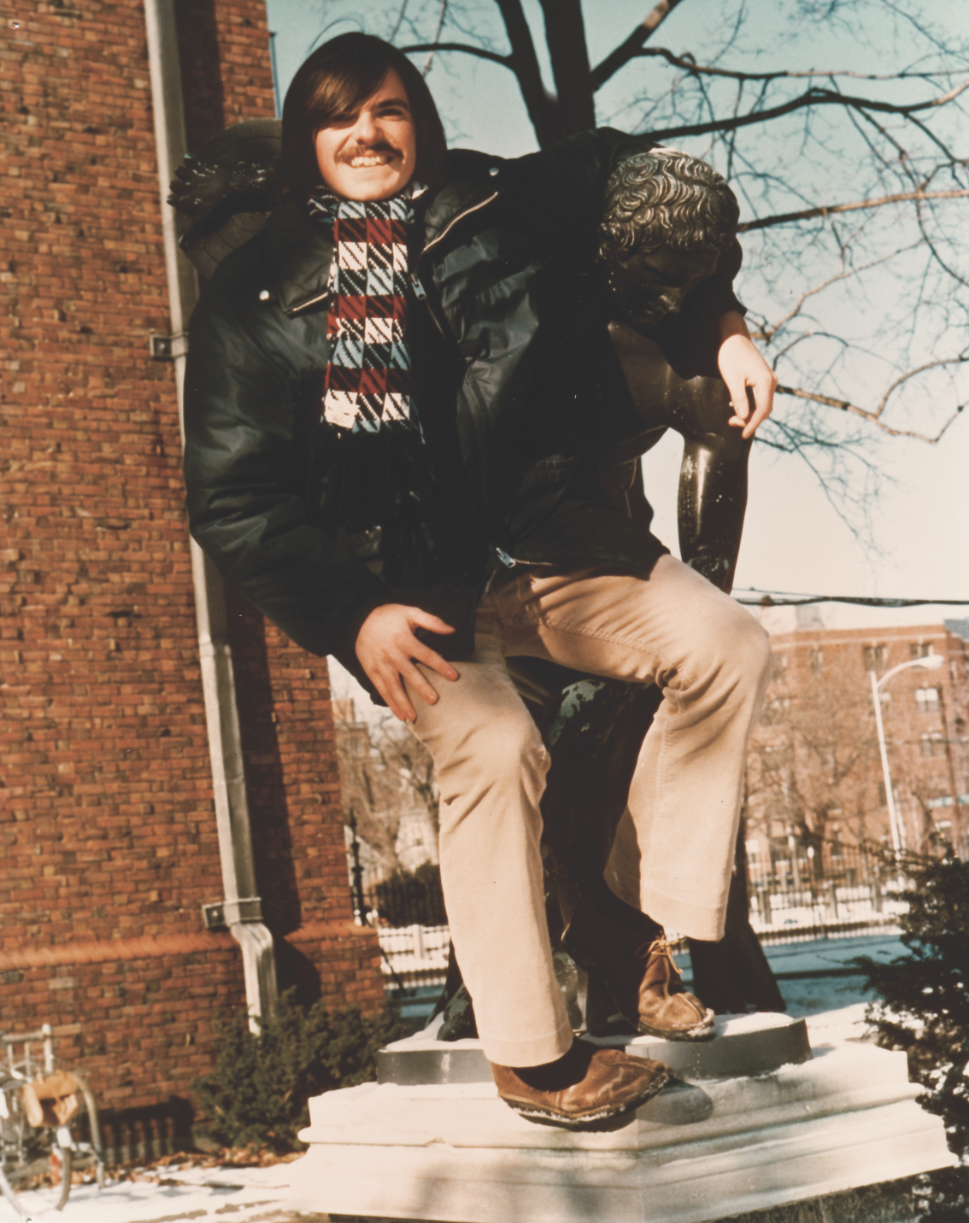

Freshman fall at Princeton, he was trying to make the tennis team when he ran into an Episcopal friend, David Page, near Jadwin Gymnasium. “Why don’t you come inside and give the squash team a try,” Page said. Callahan gave the squash a go. “I loved it from day one,” he said. “Bill [Summers, the men’s coach] was hilarious. He had a great sense of humor, kept us laughing. Right from the beginning I enjoyed it.” Despite the laughs, the team was training hard; during the winter holidays that year, the campus dorms were closed due to the energy crisis, and Summers had the team sleep on cots in the gym.

Recruited for tennis, he played on the Tiger tennis team all four years—becoming the last Princeton man to letter for both varsity tennis and squash teams. The tennis team was quite good, sometimes getting ranked in the top ten in the country. And he taught tennis at Merion in the summers.

But his heart was increasingly focused on a game he had hitherto taken for granted. As a freshman, he started at No. 8 and ended up at No. 6 on the squash ladder; sophomore year he ended up at No. 3 and his last two seasons he ended up at No. 1. He was a two-time All American. The Tigers were in the midst of a fantastic run—over the course of a decade they lost just five matches. Callahan’s freshman year, they ended Harvard’s eight-year, 44-match win streak and officially tied for the national championship with the Crimson, Princeton’s first national squash title since 1955. As a sophomore against Yale, he clawed back from an 0-2 deficit to win in a fifth-game tiebreaker and Princeton nailed down an undefeated season. His junior year they finished second to Harvard, but his senior year, when he was captain, the Tigers again had an unblemished record. Callahan was an economics major—his thesis was on patent law and generic drugs—and was a member of the Cottage Club eating club. He still annually gets together with his Blair Hall rooming group, which includes teammate Dave Bottger.

After college and a summer at Merion, Callahan started his job at IBM at their Springfield, New Jersey, offices. On his first day of work, he met Kristen, a trainee in another office in the same building. They were married a year later. For four years, Callahan sold data processing units and high-end computing software to colleges, medical institutions and other public sector organizations. First living in Union, Bob and Kristen moved in together in Maplewood, NJ.

A hurt shoulder brought him back to Princeton. In 1980 Norm Peck, Princeton’s head coach (he had been the assistant when Callahan was an undergraduate), underwent surgery for a bum shoulder, and afterwards he couldn’t feed balls and work on court; Princeton gave him a year’s sabbatical to rehab his wing. Peter Thompson, a recent Princeton graduate, was applying to business school and agreed to take on the team for the year. Princeton went undefeated that season. Then in the summer of 1981, Thompson went to business school, and Peck decided not to come back. He had moved to San Diego and had taken a job with Ektelon, the sporting-goods manufacturer— he eventually became president of Ektelon. Thus the search committee. Thus Callahan.

Taking the job early in the fall, Callahan was so sure of his plan to return to IBM that he kept the Maplewood house and commuted for a year. He didn’t know that much about coaching squash, having never actually done it. “I had coached tennis and knew that there must be a corollary for squash,” Callahan said. “I remembered what it was like when I was a freshman at Princeton. I also memorized [Jack Barnaby’s] Winning Squash Racquets and used that as law.”

That first year he figured it out enough to lead Princeton to another undefeated season. The one close match was up at Harvard. It was 4-4 and the No. 6 match, between Rich Zabel and Spencer Brog, was one of those classic collegiate matches. Brog won the first two games, both very close. He was up 4-0 set-five in the third but Zabel scrambled back and at 4-all hit a shot into the front left corner for a winner. “It was on a back-court at Hemenway and I couldn’t get near it,” Callahan remembered. “After the third game, I told Richie to ‘keep it going’ or something inane.” Zabel then took the next two games and preserved the perfect season.

That first year he figured it out enough to lead Princeton to another undefeated season. The one close match was up at Harvard. It was 4-4 and the No. 6 match, between Rich Zabel and Spencer Brog, was one of those classic collegiate matches. Brog won the first two games, both very close. He was up 4-0 set-five in the third but Zabel scrambled back and at 4-all hit a shot into the front left corner for a winner. “It was on a back-court at Hemenway and I couldn’t get near it,” Callahan remembered. “After the third game, I told Richie to ‘keep it going’ or something inane.” Zabel then took the next two games and preserved the perfect season.

What typically could have happened is that Callahan might have stayed for those allotted three years and returned to IBM. After all, six men had led Princeton squash in the previous fourteen years. It was a revolving door. It didn’t pay well. Moreover, Callahan was still a tennis guy in some ways. He served as the assistant coach for the Princeton men’s tennis team (under his old college squash coach David Benjamin) from when he returned to Princeton in 1981 until 1998. (“I was very disappointed in 1998 when my position was terminated after an NCAA evaluation process,” Callahan said, “but then it wasn’t long before coming home for dinner was great.”) In 1983 he also started working at Bedens Brook Club, a tennis and golf club in Princeton, where he taught tennis full-time each summer through 2011. He hates the sun and teaching tennis all day in the summer is painful for a person like that, but he never lost his love of tennis and couldn’t stay off the court.

By force of personality and strength of vision, Callahan became a central figure in U.S. squash. Eight months after coming to Princeton, he started the world’s first major summer squash camp. Linking up with Head, the sporting-goods manufacturers based in Princeton, Callahan created the camps in 1982 by inviting the top juniors from around the country for week-long sessions. He constantly innovated at these camps, doing things that no other coach was doing: bringing in pros for exhibitions, using video, teaching about Nautilus and other strengthening programs, starting (in 1984) the first adult camps and using psychologists. (At the 1983 camp, none of us campers had ever heard of Nautilus fitness equipment.) Callahan created many of the typical features of summer camps today. His camp, now run by Gail Ramsay, is still the standard by which all others are measured.

By force of personality and strength of vision, Callahan became a central figure in U.S. squash. Eight months after coming to Princeton, he started the world’s first major summer squash camp. Linking up with Head, the sporting-goods manufacturers based in Princeton, Callahan created the camps in 1982 by inviting the top juniors from around the country for week-long sessions. He constantly innovated at these camps, doing things that no other coach was doing: bringing in pros for exhibitions, using video, teaching about Nautilus and other strengthening programs, starting (in 1984) the first adult camps and using psychologists. (At the 1983 camp, none of us campers had ever heard of Nautilus fitness equipment.) Callahan created many of the typical features of summer camps today. His camp, now run by Gail Ramsay, is still the standard by which all others are measured.

Unable to stand pat, Callahan spread the camp idea by flying out to weekend camps around the country and by organizing sessions for coaches to train other coaches. He joined the board of the CSA and twice served as president. He assumed the role of rankings and seeding and organizing the season-ending tournament draws which became much more complicated once the national men’s team tournament was started in 1989.

Another pioneering move was the overseas trip. Other collegiate teams occasionally took training trips abroad, but beginning in the fall of 1983, Princeton systematically took one every four years. They went to London usually, playing Oxford and Cambridge and matches at the Royal Automobile Club; more recently they’ve gone to Egypt and France.

These trips, especially the ones in 1983, 1987 and 1991, opened his eyes to the inevitability of softball supplanting hardball. Callahan started going to the British Junior Open. He was the only collegiate coach at the BJO most of the time—the other coaches sometimes asked why he was there since he wasn’t actually coaching anyone. One year he videotaped the finals of every age division and gave the tapes to the USSRA so they could see how far behind American junior squash was.

Callahan became the primary driving force behind the change to softball for male collegiate squash, a prolonged, fractious and sometimes muddled campaign that ended in the spring of 1994. He might have been the most prepared Americanborn coach for the switch. He had brought in Neil Pomphrey as assistant coach two years earlier. Pomphrey, a theoretician at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, had grown up playing squash in Edinburgh. After living in California, Pomphrey came to Princeton and played with Callahan on Princeton’s team in the Philadelphia SRA singles leagues. Replacing Fred Gerstell as assistant in 1992, Pomphrey helped smooth Princeton’s transition to softball.

Soon after the switch, Callahan had the idea of hosting the 1998 World Junior Men’s Championship. The U.S. had never hosted a world championship; the very idea of it was absurd on a few levels. But Callahan thought U.S. juniors would benefit from the exposure to world-class squash and U.S. coaches to world-class coaches— he organized a coach’s conference during the fortnight. He also bussed in local kids who had never seen squash before.

Peru was first in line for the 1998 championships, but when their bid fell through, the World Squash Federation took a leap and awarded it to Princeton. Callahan did it almost entirely alone. He had a $300,000 budget and the teams’ entry fees—thirty-two teams at $3,000 each—meant that he had to raise about $200,000 himself. “I had some sleepless nights,” he said. “I was thinking, ‘My kids are never going to college.’” One night at a hotel during a trip to Williams, he disappeared into the bathroom. His roommate, Neil Pomphrey, fell asleep. Hours later, Pomphrey woke up. The light was still on in the bathroom. “I yelled, ‘Is everything alright, Bob?’ He came out. He had been reading the WSF manual on running a world championship. ‘I think I might have bitten off more than I can chew,’ he said.” In the end he secured a sponsorship from Merrill Lynch, some support from Prince and Princeton alums and made up the difference with ticket sales.

It was a seminal moment for U.S. squash. Callahan put a glass court on the indoor track on the ground floor of Jadwin. He piped a rented air-conditioning system into the squash courts down below. The team finals went down to the last match. It was a thrill and squash was never the same in the States again. For Callahan, Princeton Squash boomed. Players like Yasser El Halaby first came to Princeton at the tournament; coaches now were familiar with the school and would send Callahan potential players. Princeton solidified itself as the main challenger to the Trinity College juggernaut.

There were some tremendous successes over those years, especially with El Halaby and the Yik brothers, but the era also included the squandered match point in the 2006 regular season “Atlas Lives” match against Trinity and four straight years of losing in the finals of the national teams to Trinity, including twice at Princeton by 5-4 scores. Callahan never let defeat define his team or his own career. He was always more than simply wins and losses. He spent many hours with me going over in fine-grain details the 2009 national team finals, a galling, painful loss that was the main story of the book about Trinity’s Paul Assaiante, Run to the Roar; most coaches would have not wanted to relieve each match, blow-by-blow, the way Callahan did. “He never says anything bad about anyone,” Gail Ramsay said. “He’s consistently warm and welcoming, always putting other people first.”

There were some tremendous successes over those years, especially with El Halaby and the Yik brothers, but the era also included the squandered match point in the 2006 regular season “Atlas Lives” match against Trinity and four straight years of losing in the finals of the national teams to Trinity, including twice at Princeton by 5-4 scores. Callahan never let defeat define his team or his own career. He was always more than simply wins and losses. He spent many hours with me going over in fine-grain details the 2009 national team finals, a galling, painful loss that was the main story of the book about Trinity’s Paul Assaiante, Run to the Roar; most coaches would have not wanted to relieve each match, blow-by-blow, the way Callahan did. “He never says anything bad about anyone,” Gail Ramsay said. “He’s consistently warm and welcoming, always putting other people first.”

All those close losses were redeemed on 19 February 2012 when at Princeton, Callahan led the Tigers to a comeback victory over Trinity, ending the Bantam’s 13-year run as national champions. It had been similar to 1993. They had lost to Trinity 7-2 in the regular season and at home for the national teams managed to charge past with a 5-4 win. The image of Callahan that Sunday afternoon was the image from so many of his winter afternoons these past 32 years: a blank gaze, his competitiveness and lack of ability to do anything tearing him up inside. That day he was pacing back and forth along the hallway, unable to find a seat in the gallery to watch the final match. When the hands went up and the roar reverberated, his face was a picture of relief.

I talked with Callahan Tuesday the 21st of February for a couple of hours, and he told me how exhausted he felt, the sense of release so overwhelming. That same day he felt some tingling in his arms, like they had fallen asleep. A few days later he felt the tingling again. On Saturday he called his doctor and went into the University Medical Center at Princeton. They found a dark mass on his brain and kept him overnight. On Sunday, they ran a MRI.

Exactly a week after he had secured the culminating win of his career, doctors told him that he had cancer.

On the right side of his brain was a stage 4 glioblastoma multiforme, a malignant tumor, perhaps the most aggressive kind of cancer. On Tuesday he told Gail Ramsay, the Princeton women’s coach and old friend from Cynwyd. He didn’t go with the players to the national individuals the following weekend, telling them that he had a family issue. Many thought it must be something to do with Kristen Callahan, especially since she traveled with the team regularly that winter to away matches, something she hadn’t done before. He went into Sloan-Kettering in New York that weekend to prepare for surgery on the Monday after the individuals. That Sunday night, once the players were back, Neil Pomphrey arranged for the captains to hold a team meeting in a dorm room. Callahan called in to tell the team the news. For many of the players it was the most emotional moment of their lives.

On the right side of his brain was a stage 4 glioblastoma multiforme, a malignant tumor, perhaps the most aggressive kind of cancer. On Tuesday he told Gail Ramsay, the Princeton women’s coach and old friend from Cynwyd. He didn’t go with the players to the national individuals the following weekend, telling them that he had a family issue. Many thought it must be something to do with Kristen Callahan, especially since she traveled with the team regularly that winter to away matches, something she hadn’t done before. He went into Sloan-Kettering in New York that weekend to prepare for surgery on the Monday after the individuals. That Sunday night, once the players were back, Neil Pomphrey arranged for the captains to hold a team meeting in a dorm room. Callahan called in to tell the team the news. For many of the players it was the most emotional moment of their lives.

The next morning, Monday 5 March 2012, he went into a five-hour surgery. He was home by Thursday. On that Sunday, three weeks after winning the title, he was reunited with his team.

He did a six-week regiment of radiation and chemotherapy. He experienced extreme fatigue. He took more chemotherapy pills and steroids. In June he and his family attended his 35th Princeton reunion, including walking in the P-rade. Two weeks later he and the family were up at Buck Hill Falls in the Poconos for Father’s Day—the first Father’s Day in which he was not working since his first son arrived. On the Fourth of July he celebrated his 57th birthday. In September Bedens Brook honored Callahan for his 29 years of service. In October he was inducted into the U.S. Squash Hall of Fame. At the same time MRI’s revealed that the tumor was growing again, so Callahan started an experimental Novartis drug.

Remarkably he coached out the 2012-13 season. It wasn’t easy. Sometimes he would have episodes of confusion putting together pairings for practice. He took naps most days. Sometimes he would crawl under his desk and catch an hour’s sleep. He still got on court feeding balls and he still ran the team with his trademark enthusiasm. “He maintained the cohesion amongst the team,” said Pomphrey. Princeton ended up winning a share of the Ivy League title. At the national teams, they lost in the semifinals to Harvard 5-4 but his players allowed Callahan to go out a winner as the Tigers beat Yale 6-3 in the 3/4 playoff in the final match of his career, notching win No. 324.

Remarkably he coached out the 2012-13 season. It wasn’t easy. Sometimes he would have episodes of confusion putting together pairings for practice. He took naps most days. Sometimes he would crawl under his desk and catch an hour’s sleep. He still got on court feeding balls and he still ran the team with his trademark enthusiasm. “He maintained the cohesion amongst the team,” said Pomphrey. Princeton ended up winning a share of the Ivy League title. At the national teams, they lost in the semifinals to Harvard 5-4 but his players allowed Callahan to go out a winner as the Tigers beat Yale 6-3 in the 3/4 playoff in the final match of his career, notching win No. 324.

He announced his retirement in mid-April. The praise poured in. Two dozen coaches extolled his many virtues in an article on the CSA website. Craig Sachson, the sports information officer at Princeton, published a 5,000-word paean to Callahan. In June two hundred people gathered at Jadwin for a surprise retirement party. There was a slideshow and a party in the showcourt and a lot of hugs.

After he retired, doctors discovered that the cancer was growing again in Callahan’s brain, flaring up outside the original tumor. In late spring he again underwent a regiment of radiation and chemotherapy which is continuing today. He still has yet to lose his hair. He has faced the cancer with the kind of equanimity that a parent with five boys under the age of five quickly learns. He uses the word “fortunate” in almost every sentence.

This summer he and the entire family, including the first granddaughter, are spending a week at the Wyant family house in Sea Island, Georgia. Scott, son No. 3, is getting married. There are hopes of traveling to Europe in the fall.

With his penchant for detail, Callahan knows what lies ahead for him. He is honest about the numbers. He told me that the statistics are horrible for a stage 4 brain tumor, that the median survival rate is 15 months, that only 3% live for three years with it. He has passed the 15-month mark. He is beating the odds. “I’ve been lucky and hope that I can be lucky to stick around on this earth for a little while longer,” Callahan said. “’I’ve led a charmed, blessed life and I hope I can keep going.”

When he snatches on his jacket, it is orange and black rather than blue, but otherwise what John Milton wrote in his beautiful 1638 elegy “Lycidas,” reminds many of Bob Callahan these days and all of his days:

And now the sun had stretch’d out all the hills,

And now was dropt into the Western bay;

At last he rose, and twitch’d his Mantle blew:

To morrow to fresh Woods, and Pastures new.