By Richard Millman, Owner – The Squash Doctor Corporation

Approximately 80% of our sport is played at the back of the court, behind the short line. This is where rallies are constructed, where opportunities are seized or lost, where dominance and control are established—and where surprisingly little practice and teaching is done, relative to the way the game is really played.

Let’s stop and think for a moment. Where do you see the majority of coaching happening? Do you more often see the coach standing at the back feeding or at the front? Naturally intermediate and beginner players need to learn good fundamentals, and it is pointless putting them in a situation where they have neither the skills nor the confidence to maintain a quality practice.

However, as a player has learned good fundamentals and for experienced players, it is imperative that the time spent practicing reflects the way the game is played. By doing this players become more confident in their abilities.

In the back corners, the multitudinous possible combinations of bounce are utterly beyond the capacity of even an extraordinarily astute human being to consciously predict. If we try to use our conscious minds to calculate how a ball will react and where to position for every possible formulation, we will not only fail but we will lose all confidence.

Consider this-far-from exhaustive list:

sidewall, backwall, floor;

sidewall, floor, backwall;

sidewall, floor; backwall, floor;

backwall, sidewall, floor;

backwall, floor, sidewall;

sidewall, backwall nick;

backwall nick;

sidewall nick.

And there are several more combinations.

How do we learn to perfect the ability to deal with all of these?

As always, everything begins with Racquet preparation. If you have followed my earlier articles you will have read that Racquet preparation is the beginning of the planning process. The simple act of preparing the racquet triggers advance planning thought in the subconscious mind.

The subconscious is our most valuable survival system. Through millions of years of evolution it has developed an almost supernatural ability to assess situations instantly and to provide our feeble little conscious minds a menu of best options from which to choose to execute.

However, this only works if you give the subconscious mind the correct parameters with which to make its assessment. If you don’t prepare the racquet and, in doing so, declare your intent to your subconscious mind, it will give you a full menu of ways in which to kick or run over or jump on the ball. Humans haven’t been through evolution with a racquet in their hands.

Once you prepare your Racquet, your subconscious mind will, at light speed, supply information to your conscious mind and body as to what adjustments to make, to deal with the specific situation that you are encountering.

Now, the conscious mind is not utterly useless and this is where practice comes in handy. Expose yourself to similar situations often enough and you will learn from experience.

A simple drill that everyone should do regularly with a partner, is boast/crosscourt. Don’t think that I am recommending this drill as a piece of strategic advice. I am not recommending that everyone should play crosscourts and defensive boasts-far from it. No, I am offering this as a skill development practice. If you regularly put yourself in a situation where you have to retrieve 75 to 150 well-struck crosscourts from the back corners, while continuously moving back into position to defend the court before your partner hits the next ball (and if you get your Racquet prepared before you start moving—and if you visualize your target effectively) then you will rapidly become proficient at dealing with the multiple combinations of weird and varied bounces that occur in the back corners.

This is a starting point.

I recommend that you and your training partner take turns at both the cross-court and the boast roles and that you do a minimum of 300 shots (3 x 100 each) in each corner, per session. If you do this for at least three weeks, you will find your confidence and familiarity with the back corners increases markedly.

The progression of this drill is to change from boast/crosscourt, to boast/straight drive to yourself/hit a boast off of your own drive back to your partner to crosscourt.

This requires additional skills and you shouldn’t attempt this until you have really polished the first drill.

As with all drills, your main focus should not be hitting the ball. Your main focus should be your Racquet preparation (the PLAN) and your movement (the energy supply for the stroke and the method by which you guarantee the correct angle of approach to the ball).

When fulfilling the self drive/boast from your own drive portion of the drill you must really focus on getting there to leave and not to hit. You should also choose a pace at which to hit the ball that gives you plenty of time to be ready for both your own shot and your partner’s crosscourt.

Again this needs to be done regularly, repetitively and until confident. Perhaps on 5 or 6 occasions at least until you start to feel that you are becoming proficient.

Don’t get despondent if you can’t do it very well the first time out. Players that give up at this stage will not fully develop their potential and will remain in the lower ranks of ability.

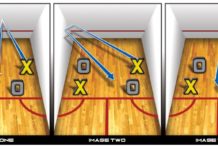

Once you have achieved a high level of regularity with these two drills, you should start trying some of the various back court or ‘length games.’

The most common of these is to play everything past the short line—and indeed it is an excellent game that I have used for training all levels of competitive players (including professionals) as there is so much nuance and subtlety available as a learning platform in this game.

However, I would recommend starting off with two other conditioned games. First, the above-the-Service-line game—commonly referred to as the ‘above-the-line’ game. In this game the ball does not have to go past the short line (only above the service line) to any length. It is an excellent training game for many reasons, but in the instance we are discussing (the back court) it offers an excellent opportunity to encourage early Racquet preparation and the development of skills in ‘getting the ball out of the back corners.’

I typically play games to 15 points.

If you are doing well with the ‘above-the-line’ game (i.e., multiple shot rallies of ten or more shots), the next progression i would recommend is the version of the length game where the ball is allowed to bounce once before crossing the Short line. This game demands that you learn a number of subtle skills. Apart from learning how to get the ball out of the back corners it:

a. helps to develop the ability to recognize a threatening ball from your opponent that must be intercepted;

b. encourages you to volley at all possible times;

c. helps you to learn how to precisely target your length shots with a degree of accuracy similar to that which you try to use when playing drops and kills at the front; and

d. encourages you to move up the court into a dominant position to offer maximum opportunity to seek volleys so that, should you be unable to volley, your line of approach to the back corner is sufficiently steep to allow you the best space and leverage with which to play out of the back corners.

Again this game is typically played to 15 points.

When you feel that you have become proficient at this game (and only then), I would recommend you progress to the classic ‘length game,’ where the ball must bounce over the Short line at all times.

I have used this game as a teaching platform with advanced players for many years. As students learn to recognize subtle situations which repeat time and again, and to proactively prepare corrective decision making technique to allow themselves to survive in the rally where they have previously made either actual or judgment errors, the student gradually elongates the duration of the game.

To this end I typically time each game with a stop watch. Using PAR to 15, most players who have not played this game at an advanced level with a pro are unable to get much past 7 minutes. But with practice and by learning to carefully look for dangerous situations, and by developing expert targeting and volleying skills, it is possible to extend one game to 30 or 40 minutes. It usually takes a dedicated student in the region of a year (if practicing once a week-quicker if doing intensive sessions like camps or daily training) to attain this level.

The ultimate challenge in the back court game is Length game in the Channel. Using the width of the service box as the ‘Channels’ on each side, the ball must land behind the Short line and within the width of the service boxes on either side of the court. This requires a high degree of expertise and it is not uncommon for players of 4.5 or even 5.0 level to fail to score a single point in a game up to 15 against a seasoned pro. This is because the precision with which a seasoned pro both aims and ‘feels’ the targeting of length shots is vastly more focused than a typical club player. Even a talented college player or young professional may find this game too exacting to begin with until the subtleties and skills required are explained and practiced.

Please don’t try this unless you have gone over it with an expert and analyzed each individual situation that comes up. If, however, you have managed to improve your time against your coach on the regular Length game to a point where you are regularly achieving 15 minutes or more, and provided the coach feels you are ready for it, by all means give it a go.

All these games require excellent and precisely executed techniques for both movement and ball striking (hitting). Any lax attitude toward execution will result in failure.

Remember the game is 80 percent length. If you want to succeed, you had better perfect that portion of the game. It’s no good having a really sexy short game if you can’t play the majority of the game to a level of excellence. You simply won’t get the opportunity against an opponent who knows and ‘feels’ the back of the court.

So good luck, practice hard, confront each subtle situation as it arises, retain the information you glean from each failure for later correction and success and finally, listen to your trusted coach to learn when and how to intercept (whether with a volley or a half-volley) and how to target with volleys, half-volleys drives, accurate floats, the occasional skid boasts and lobs.