By Damon Leedale-Brown, Sports Scientist & Conditioning Specialist

The understanding of ‘talent’ in sport—or indeed across other domains such as music and business—is an area which has received more extensive investigation over the last 10-20 years. Take the 1991 research of Florida State University psychologist Anders Ericsson in which they studied a group of violinists at the renowned Music Academy in Berlin, Germany. The violinists were split into three groups: Group 1 were the outstanding students expected to become international soloists—the kids considered lucky enough to have been born with a gift for music; Group 2 were still good performers but not considered at the same level as the top performers—most likely to have a future in the world’s top orchestras but not leading soloists; Group 3 were considered the least able of the students on a path to become music teachers. After a series of detailed interviews, the researchers found that the background of the three groups was remarkably similar—most students began practice alongside formal lessons at 8-years-old and, on average, first decided to become musicians just before turning 15. However, the one dramatic and unexpected difference between the groups was the number of hours that had been devoted to focused and purposeful practice. By the age of 20 the best violinists had practiced an average of 10,000 hours—2,000 more than the good violinists in group 2, and over 6,000 hours more than the violinists in group 3 hoping to become music teachers.

These findings link into research in the field of Longterm Athlete Development (LTAD) which, for some time now, has alluded to the fact that in most cases it takes around 10 years of purposeful training to reach World-Class level in any sport. In his book, Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell points out that most top performers practice for around 1,000 hours per year hence the ten year rule now being defined as the 10,000 hour rule.

Consider some of the so called child prodigies in sport—Tiger Woods had a father who was obsessed with the idea “that practice creates greatness” and started his son in golf at what he describes as an “unthinkably early age,” before he could even walk or talk! Before he was 3-years-old Tiger could already hit the ball 80 yards with his 2.5 wood, and won his first national major event at 13. By his mid-teens, Tiger had clocked over 10,000 hours of dedicated practice. Reliving his early years in tennis (from his autobiography Open) Andre Agassi wrote, “my father says that if I hit 2,500 balls each day, I’ll hit 17,500 balls each week, and at the end of one year I’ll have hit nearly 1 million balls. ‘Numbers,’ he says, ‘don’t lie.’ A child who hits one million balls each year will be unbeatable.”

Of course there are very real dangers to starting a child on a path of intensive and long hours of practice at such an early age. One of the leading Sports Science experts from England has said, “The only circumstance in which very early development seems to work is where the children themselves are motivated to clock up the hours, rather than doing so because of parents or a coach. The key is to be sensitive to the way the child is thinking and feeling, encouraging training without exerting undue pressure.” Psychologists typically call this “internal motivation” and it is often lacking in children who start too early or who are pushed too hard, putting them on a road not to excellence, but to burnout.

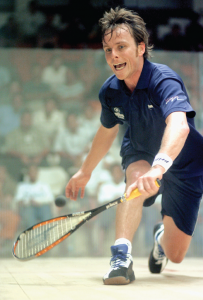

Moving back to squash, let’s consider some of the current and recent World’s top players. Current World No. 1 Nick Matthew is aged 31 and became World No. 1 at age 30. Nick has consistently been in the top 10 since 2006 (at age 26), having turned professional at age 18 following a successful junior career and with well over 10,000 hours of deliberate practice behind him. Peter Nicol reached World No. 1 at 25 years of age and held this position for 60 months. Amr Shabana become the first Egyptian to top the World rankings in 2006 when he was just short of his 27th birthday, and went on to hold this position for 33 months. Nicol David began playing squash at 5, and has been World No. 1 for the past 5 years since the age of 24. Laurens Jan Anjema (LJ) who we have discussed in the previous two articles, reached a career high to date of World No. 9 at the age of 27, having really begun to apply himself to a career as a professional squash player at age 18.

So what are some of the key messages that we can take away from our series of articles on Talent and the pathway taken by pro player LJ if we truly have the desire and drive to become excellent in our sport:

1. Parental support, not pressure;

2. Develop relationships with coaches and other professionals (i.e. fitness coaches, sports psychologists etc.) who you trust and believe are committed 100% to taking you to the next level;

3. Look for the role models who help ignite your passion for the game—this could be your coach, a top junior or pro level player;

4. Do it because you want to and have a love for the sport—internally motivated young athletes tend to regard practice as fun, not as a chore and, as such, are not afraid to constantly challenge themselves in the practice environment;

5. Understand the connection between input, process and output. As LJ puts it, “Input is the advice that a coach or expert provides me, process is the work I put in based on this advice, and output is the final result.” One week of a high level training camp will not transform your game, but application of the knowledge you gain from such experiences applied with purpose and dedication over the coming months is what will make the difference;

6. Keep learning—LJ has put in 10 years of purposeful practice and hit thousands and thousands of squash balls but is still striving for the next level of understanding and challenge in his training that could help him become a better player.

So it seems that there are no quick fixes to becoming excellent, as I am sure many of you have found out! There is little, if any, evidence to suggest that World-Class performers have a god given talent, and it really comes down to hours and hours of purposeful practice over many years. Of course purposeful practice is typically extremely challenging mentally and physically and, as such, “is not inherently enjoyable.” The reward comes in the success that is gained long term from a dedicated approach to training and practice. If the activities that lead to excellence were easy and fun, then everyone would do them and there would be nothing to distinguish the best from the rest!