By James Zug

Photos by Dick Druckman

Squash Magazine’s senior writer James Zug is back with another book. In the summer of 2003 we proudly ran an excerpt from Squash: A History of the Game, which came out that fall from Scribner. It was a best-seller in the squash world and earned rave reviews from literary critics. The Financial Times called it “a terrific read.” The New Yorker said that Zug, “excels in describing the game’s outsized personalities and how they won clubhouse fame and infamy.”

Soon after the book came out, Trinity squash coach Paul Assaiante called Zug to discuss putting together a book about the lessons he had learned over a thirty-year coaching career. After nearly seven years of interviewing, researching and writing, the result is Run to the Roar: Coaching to Overcome Fear, being published this month by Penguin.

In one respect, Run to the Roar is a sequel to Squash, as it covers the most dominant story in American squash since Squash appeared: the Trinity dynasty and their 224-match win streak which is the longest in collegiate sports history. And it has a famous author’s foreword: in 2003 it was George Plimpton; here it is Tom Wolfe, who wrote a typically exuberant and insightful introduction. (The book also has a wonderful afterword by Jimmy Jones, the president of Trinity College.)

Run to the Roar is for parents and coaches who want to learn how to mentor the young athletes in their lives. It is the inspirational, intimate autobiography of Assaiante who overcame great adversity to understand the most effective ways to lead, develop teamwork and sustain growth in a high-pressured environment. Assaiante reveals many behind-the-scenes moments from the Trinity streak.

The framework of the book is a single dual match: Trinity v. Princeton on 22 February 2009 in the finals of the national intercollegiate team championships. In three matches Princeton was on the verge of clinching a fifth victory and securing the dual match. Eventually, Trinity escaped 5-4 and captured their 11th straight national title (in February 2010 they won their 12th.)

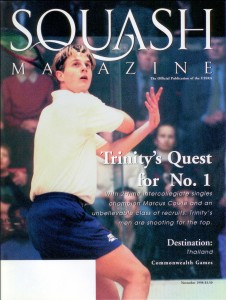

The most surprising match might have been at #2 between Gustav Detter of Trinity and Kimlee Wong of Princeton. In February 2006, Gustav—a freshman from Sweden, he was known as Goose—had orchestrated an unprecedented comeback against Yasser El Halaby, surviving a match point in the third game to win in five and thus enable Trinity to sneak past Princeton 5-4. Owing to an iconic photograph by Dick Druckman and the subsequent headline on the cover of Squash Magazine, the moment was known as the Atlas Lives match. Now three years later the freshman is a senior but faces a similar situation. He is down 0-2 in a match against Princeton, with his team desperately needing a win.

What follows is the end of chapter six of Run to the Roar.

—The Editors

After the second game against Kimlee today, Goose comes off the court and I know what’s going on. He is frozen and confused. The pressure has sapped his energy; the running has sapped his brain. His eyes are fibrillating as he blinks away the thought of losing.

He has grown up tremendously during his four years at Trinity. He is about to graduate with a 3.93 average, having majored in economics with a minor in Chinese. He has a girlfriend from Connecticut. He is our Doug Flutie, a short, clean-cut, likable kid who once pulled off a miracle. But with all the growth, he is no longer innocent. One miracle is asking a lot; a second miracle is absurd. Down 2–0 to Yasser in 2006, he had a naïve confidence he could come back. Today he believes he’s going to lose.

A player’s style is dictated by his personality as much as by his physical strengths and talents. It is as idiosyncratic as a fingerprint. Goose was conservative. He was clueless some of the time and shy.

No matter what level of accomplishment a person reaches, everyone wants approval. The key is to use the “but” technique. I start off every coaching interlude with a positive remark and then interject a “but” to add a modification. This works but the opposite does not.

Today with Goose, I bypass the positive and go straight to the negative. I yell for about thirty seconds, high volume, a couple of F-bombs, intense. “This is about fighting. This is about showing me what you’ve got. You are going to have to do this on sheer guts. You are playing like Kimlee. But Kimlee isn’t my player. I don’t coach Kimlee. I only coach Gustav. Be Gustav. You can accept defeat. But Parth won’t let you accept it. Vargas won’t let you accept it. They’re dying out there on the other courts. You can’t let them down. You’ve got to prolong the points, extend each point as long as you can. Win each point three times. This is Heartbreak Hill. You’ve reached the twenty-mile mark of the marathon. Guys who hit the wall, no matter how hard they’ve trained, they will accept quitting. Not with us. Not now, not ever.”

I find it helpful to do this, to get in their grill and yell. There are times when being unruffled and patient—my standard game-day mode—isn’t the best way forward. I usually try to get them to laugh. But once in a while, I get on someone. If you do it too often, you anesthetize them to the tirade and it becomes meaningless. But if it is rare, it works.

I am not sure if it has worked with Goose. He seems as if I have slapped him. He doesn’t say a word—Scandinavian inscrutability. I tell him what I always tell players when they are down 0-2: “You and your opponent will finish the match at the same time; the goal is to make him travel farther and endure more pressure and hardship along the way.”

“Squash is like sex,” I say, giving him one of my hoary lines, trying to end with something positive. “The object is to make it last as long as possible.” He laughs and leaves me with a smile. He goes back onto the court and shuts the glass door.

The door shutting reminds me of the 2005 nationals. We were playing Harvard in the finals, up at Harvard. Bernardo Samper, in his final dual match, lost the first two games to Sid Suchde. He was too emotional, the opposite of Goose here. The crowd was yelling for its hometown hero, just like today’s crowd. I quieted Samper down. I told him he was the better player. He took a deep, slow breath and got up.

He looked at me and I knew he was calm again. When he went on the court, he turned and shut the door delicately, as if it meant the world. He went on to win in five.

Today it takes about twenty more minutes for Goose’s body to catch up to his mind. He’s down 4–1. I shift in my seat, regretting that I had yelled. Now he’s 4–1 down in the third, a long, long way from home.

Goose and Kimlee trade points for about five minutes. Then they have a short point. Goose wins it with a sweet bit of legerdemain, appearing to prepare a long drive and at the last minute flicking the ball high and crosscourt. Kimlee, normally jackrabbit quick, doesn’t have his first-game speed anymore and in desperation he smacks it off the back wall, resulting in a sitter that Goose dinks for a short drop. Kimlee has such a vast distance to cover now that he barely gets there and hits a rail right next to his body. Goose is ready for it—automatic stroke. Goose gives me a cool, subdued nod as he heads to the server’s box.

I know instantly the message. It is Samper shutting the door delicately. Goose is telling me that he will win.

It’s incongruous: He’s down 0-2, 1-4 and just five points away from defeat, and he’s certain he’s going to win? But he is right. Kimlee is tiring. This point is the first indication. It is so subtle that only a few people see it. Squash is like that. Only a player on court can tell when you’ve found an infinitesimal crack in the façade.

Goose audaciously starts to hammer away. As in all beautiful games, there is no clock in squash, and Goose makes each point last forever. He scuttles after every shot by Kimlee and drives it, relentlessly, to the back wall. He cushions drop shots, not to win the point outright, but to push Kimlee forward. He backs Kimlee out on any loose balls, claiming more and more territory. His dirty-blond hair, bottled up in a yellow bandana, flops on every lunge. Kimlee, in turn, begins to bend over in between points, trying to catch his breath. He cleans his goggles. He wipes his right hand on the wall, sometimes leaning in until his head rests against his hand. Goose is playing physically. He is about the same height as Kimlee but much bigger. They have a couple of collisions in the early part of the game and Kimlee starts to massage his shoulder and his hip. The referee, Hunt Richardson, even gives Goose a conduct warning for unnecessary contact.

Unlike most young players, Goose is no longer panicking in the face of his dwindling time on the court. He looks the same as he did an hour before. He is calm, collected, and breathing easily. I realize that Goose has climbed into the center of the storm. He is quiet inside, while the entire building is rocking, buffeted in the winds of this historic match. He works hard but without fear. Instead of feeling deflated, Goose is confident.

Three rallies—three scoring points to Goose. In the space of a minute, he has completely changed the match. He ties up the score. Kimlee goes up 6–5, three points away from victory. But he is clearly fatiguing. Goose hits a soft, high, well-placed crosscourt and Kimlee stabs at it, his feet out of position, his racquet late. It doesn’t even make it to the front wall. Kimlee will never get so close again. Goose wins 9–6.

The first half of the game, to 4–1, took twenty minutes, the second half, a punitive eight minutes.

In the fourth, Kimlee tries to reestablish his physical presence, to command the center of the court, to cut off Goose, to stop the advance, to make retreat the only option. But Goose, wearing a new shirt, comes out firing. He knows that often you are down 2–0 and you win the third, and then the other guy comes back out having caught his breath and wins the match 3–1.

Not today. Indefatigable, Goose keeps digging out balls from impossible angles and keeps making Kimlee play another shot. He flicks a crosscourt drop off every one of Kimlee’s serves to his backhand, not trying to win the point, but simply to move him up. He goes up 3–0 then withstands a ten-minute stalemate, with the score changing only once, to 3–1. It was classic, tension-filled, serve-to-score hi-ho squash: the scoreboard frozen, the boys’ tactics being employed, reconsidered, discarded. Just as in the third game, Goose wins the battle and never looks back, grabbing the rest of the points with ease. The levee is breached. Goose has broken him.

I tell him after the fourth not to relax. He should be pissed off that he has found himself in this position, tied after a hundred minutes of play. After a hundred minutes, he should be in the shower with a win.

In the fifth, Kimlee is nervous. He fist-pumps after winning the opening rally—fist-pumping at 0–0? Then he starts cramping. The game is just three minutes old and he’s exhausted. Goose comes over, the concerned old friend, not the bitter rival. Kimlee stretches against the floor and the wall. After a two-minute delay, he wins the next point. Again, a celebration. It is 1–0 in Goose’s favor. Goose wins the serve back. Kimlee appears beaten. His head droops down. At 2–0, Goose smashes three straight balls from the front of the court to the back. Kimlee backhands the first two off the back wall; he can’t reach the third. Goose goes up 5–0. Kimlee pulls it back to 5–3, but off a deep lob Goose cranks a decidedly risky volley drop shot for a winner. He’s got Kimlee on the ropes and they both know it. If this were Frazier versus Ali in Manila, it was the end of the fourteenth round and Eddie Futch would be stepping into the ring to stop it.

This time when he wins, when he pulls off another incredible comeback against Princeton, Goose doesn’t fall to his knees and raise his arms. He lies down on the court, supine, like a corpse, only his racquet twitching. Atlas Lives, no doubt, but Atlas is exhausted.

Excerpted from Run to the Roar: Coaching to Overcome Fear. Published by Portfolio / Penguin. Copyright Paul Assaiante and James Zug, 2010.