By Richard Millman, Director of Squash, Kiawah Island Club

There are perhaps more variations of the volley than of any other classic shot in the squash player’s vocabulary.

Volleys range from the simple to the spectacular, and all the variations have specific mechanics that pertain to their execution.

To begin with every volley shares a common energy source—the legs. Power is transferred from the legs, up through the torso, along the arm, into the racquet and finally into the ball.

For this reason, it must be clearly understood that standing still whilst hitting a volley, kills the weight transference and makes control and placement almost impossible.

Timing is also an imperative skill (as it is with all shots). The natural tendency when volleying is to allow anxiety to turn into rushing and to time the shot too early. Discipline yourself to delay the execution of the stroke until the last moment and make sure you follow the correct sequence—legs first then the arm.

This will also decrease the reaction time available to the opponent and increase the deceptive quality of the shot.

Ideas are the bases for shot selections and inappropriate mental conditioning can result in an inappropriate shot selection if you allow habit to be the basis for your choices. People often think that they can’t volley a given ball (perhaps an accurate lob or a fast drive) but frequently this is because the time available to execute the shot doesn’t match the time the player feels they need to execute the shot that they are visualizing. Instead of missing the volley, change the visualization to a shot that fits the available time.

For instance, if you are having trouble with return of serve, get your legs ready to move with the ball as it comes off of your opponent’s racquet, and prepare a very short backswing. When the ball comes, move in time with the ball to a point two to three feet behind the point on the side wall that the ball strikes and set yourself up at ninety degrees to the direction you want the ball to go in. Wait until the ball is almost past you, and then start your movement backwards away from the point of strike momentarily before you hit. This movement (which starts in your legs and progresses up your body in a wave of energy) will supply power to your shot. Keep your head down toward the ball even though you are moving away backwards and using a tiny swing (that is still at least sixty percent follow-through) “bunt” the ball high and straight down the side wall.

This is the simplest return. The mechanics of the arm are simple and very little can go wrong. There is no wrist or forearm manipulation, simply the transference of your body weight from the legs, up through to the body, through a very short swing, into the racquet and then into the ball.

The same principles hold true for a short swing volley during a rally. By “bunting” the ball high onto the top two or three feet of the front wall, you can maintain your position without running to the back of the court.

As you sense you have more time you can add proportionately more mechanics. In addition to legs and torso (essential), forearm (always present) and marginal upper arm (needed to transfer energy between the torso and the forearm), you can progressively add wrist and hand (in varying combinations and with varying mechanics), more upper arm, shoulders and finally hips.

Larger limbs need more time and therefore a bigger window of opportunity.

When students first learn the volley, the stroke they are usually first taught is a full swing, where the feeder gives them ample time to execute using the maximum mechanics. If the student is not severely warned that this is not the usual situation in a competitive game, they will memorize the mechanics of this entry level shot and easily fall into the trap of believing that this is “how to volley.”

Hence the apparent impossibility of volleying a high lob or serve that glances momentarily off of the side wall on its way to dying in the back corner.

Their knowledge just doesn’t fit this situation and they haven’t been given a progression to get there.

When learning new shots as a beginner or intermediate player, or even as an advanced player that has had difficulties with a specific situation, it is essential to understand that progressively more difficult feeds must be experienced and adapted to if you are going to be able to deal with the pressure of intense competition. There is never just one way of playing a shot because shots come in a multitude of degrees of difficulty and time availability.

Another valuable piece of volleying mechanics is the slice.

Slice offers precise directional control. When slicing the ball, the swing pattern of the racquet is much more linear than when not slicing. Therefore the racquet, and consequently the ball, are more likely to follow a precise line, which conforms to the line you are interested in (often a side wall which allows no margin for error).

Tennis players are familiar with the idea of carving the racquet head around the ball when serving topspin or “kick” serves. The idea is similar when slicing a volley in squash.

Imagine the ball, suspended in mid-air about eighteen inches above your head. As you swing, turn the racquet face around the back of the ball as if you were carving a tiny slice off the back of the ball.

At first you may be concerned that you will hit the ball cross-court.

As long as you set yourself up at 90-degrees to where you want the ball to go (in this case along the side wall), the ball will go straight, with the spin action of carving technique geo-centrically maintaining its line, just as a Frisbee does.

Again, prior to hitting the ball, you must prepare your legs for movement as it is the energy transference from the legs that will provide the power for the shot. Equally important, moving as you hit the ball will put you in position for your opponent’s next shot before your ball ever returns from the front wall.

The slice technique can be used for any shot where you want to emphasize precision over power.

For instance, if you are hitting an attacking volley into the front corners (either cross or straight) cutting or slicing the ball toward the nick will afford you more directional control as opposed to hitting without slice.

Chipping a lob-volley is a skill that involves a very short swing, timed at the very last moment and boosting the ball high, striking the top two or three feet of the front wall (my “magic spot”) and then dying as it strikes the side wall and drops into the back corner.

Once again the legs are essential for this technique as they must be stabilized and ready to impart power by bracing and moving against the impact of the ball on the racquet.

The mechanics involve marginal use of the upper arm, and a last moment, sudden flick of the forearm, wrist and hand, which transfer power from the legs into the ball. The movement of the arm, wrist and hand is marginal but precise and timed at the very last possible moment.

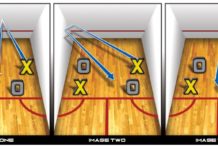

The volley-boast is a wonderful shot for any player to include in their vocabulary.

As with all shots, it can be played at a variety of speeds according to how much time you need to get into position.

When played at head height or below, the racquet head should be kept open, the legs set up for movement and the swing trajectory aimed slightly upward if you want to “weight” the shot to die at the front wall. You can, of course, hit straight through the ball, but you need to be moving early enough to cover the pace of the shot you are imparting and there is less margin for error if you hit through or down with the trajectory of your swing.

“Floating” a volley-boast to the front wall can be a very effective way of both guaranteeing your own position and working the opponent.

Before you decide to hit the volley-boast as an all-out attacking shot at pace, make sure you can cover it and that your opponent is out of position.

A hard attacking volley-boast can be a wonderful shot, when executed with a lot of wrist speed as an overhead, again using legs to generate movement and power. This is an advanced shot and should be practiced a great deal before unleashing it in the heat of battle.

A great drill for developing the volley boast is the “cross-court lob, straight length, boast drill.” Try and look for opportunities to intercept the length ball when a volley boast—but organize your movement first!

Finally drop-volleys are one of the most important shots in our sport.

As with an attacking short volley, these can be played with or without slice. Slice requires more racquet head movement, so although you may gain from directional control, if you are truly trying to drop the ball dead, you may not want the extra action of the slice mechanics. Rather you may want to just brace your legs in preparation for movement into position and as you commence your movement, delicately rebound the ball towards your target using “feel.”

The mechanics of this shot are mainly balance and stability from the legs, combined with relaxation through the torso and shoulders, but with enough muscular tension through the upper arm and forearm to provide a continuous connection between the feet/legs and the hand, wrist and finger tips that are orchestrating the delicate “tough” on the ball. The concept is to hit a shot that allows the ball to decelerate, leaving it to die in the front corner.

There are more volley techniques than those I spoke about here, but I have tried to offer a variety to you that will afford you the ability to dominate the court.

Never miss a volley.

If you feel you can’t volley the ball, reexamine the reasons that you feel you can’t. If it’s because the ball is clinging to the side wall—fair enough—it’s probably too risky.

Otherwise there is always a way of volleying. And therefore of maintaing your dominance of the court.

Manufacture an appropriate volley in the time and space you have available and take control!