By James Zug

The answer: they are in Wilmington.

Not Delaware but North Carolina. They golf not squash. They garden. They are retired, but they still work part-time publishing an annual magazine, Wilmington Today.

The question: where are they now?

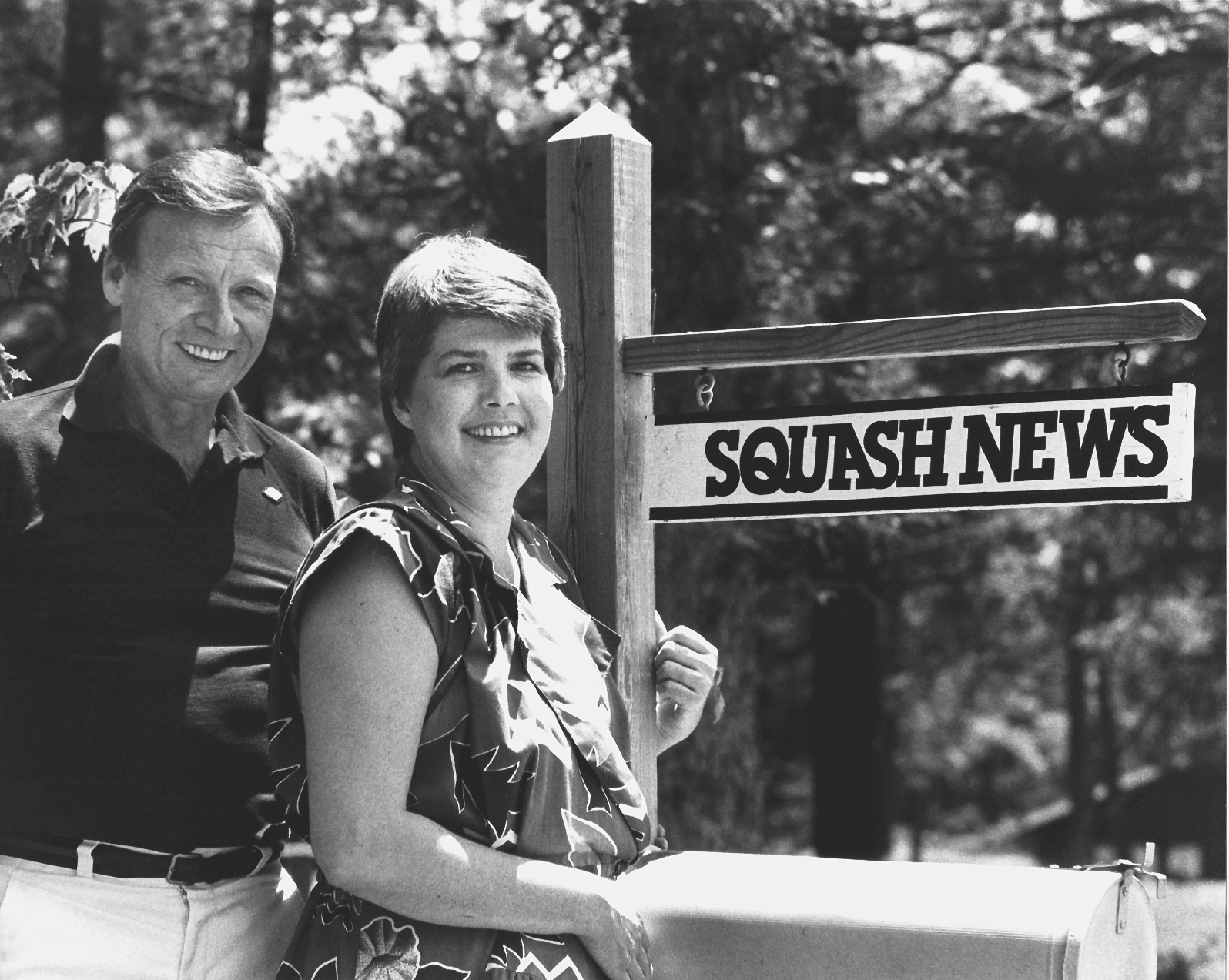

Tom Jones and Hazel White Jones were the first couple of squash for a quarter century. No one in the country was more connected, more involved behind and in front of the scenes, more private and more public, more hardball and more softball. They were tournament directors: they put on three North American Opens (1979, 1984 and 1985) and fourteen U.S. Opens, including portable glass-court events at Town Hall and the Palladium disco in New York (tournament poster designed by Frank Stella) and the Harvard Club of Boston. They spearheaded squash’s foray into the Olympic movement and the Pan-Am Games and the shift from hardball to softball. Most of all, between 1978 and 1999 they published more than two hundred and thirty issues of Squash News.

They were born trailblazers. Hazel was from Indianapolis, one of eleven children, and when she moved to New York, she became one of the few women stockbrokers on Wall Street. Tom grew up in Rochester, attended Ridley College in Ontario and Williams. He was a good singles player—he won the Genesee Valley singles three times. Once he moved to New York to work in advertising, he ensconced himself at the Racquet & Tennis Club and became a very proficient right-wall doubles player. He won the city doubles title twice and in 1977 won the U.S. and Canadian national veterans (40+) titles (with John Swann).

Despite Tom’s background, he was a free spirit (he had a tattoo on his forearm, managed musicians and bartended for a while at an Irish pub on East 94th Street) and up for anything (he joined in the ultimate squash fandango, going to the 1970 world pelota championships in San Sebastian, Spain). He loved to play the piano, banging out tunes in a pub by ear. “He was a true bon vivant,” said Palmer Page, an old friend. “He had a great deal of energy. He did things because they needed to be done. He loved the game. He had a great sense of humor. You’d leave after having lunch with him and have the biggest smile on your face.”

Tom met Hazel White through a work friend. They dated for a year. One Sunday night, while having some beers, they decided to move in together, and the following Friday, having snuck around the mandatory ten-day blood test wait, they went as far as getting married at City Hall.

Hazel joined Tom at his advertising agency. One client was a string of commercial squash clubs for whom they tried to scrounge up media attention. This led to a brilliant idea—why not start a national magazine for squash? It would serve as a great publicity machine for Insilco, the company that was just starting to sponsor a national B and C-level championship series and spread the word about the game itself. Of course, they had no journalistic experience whatsoever.

It worked. They got the local clubs and Met SRA to sign on, offering a 50% discount (and free tournament entry forms) on a $5 annual subscription. In April 1978 a sixteen-page black-and-white tabloid appeared. It had an initial circulation of 6,000.

Looking back after more than thirty-two years of technological advances, it might appear to pretty minor, but the appearance of Squash News was a groundbreaking change for the game. The magazine made the sport look a thousand times more professional; it united all the disparate factions and districts around the country in a way that the national association, then called the USSRA, had never been able to do; and it paved the way for the USSRA to develop—when the association adopted Squash News at the end of 1978 as a benefit of membership, it finally had something tangible and newsworthy to offer members. And a vehicle to growth: when Squash News started, it had just 2,000 members.

Squash News was a two-person show. Hazel was the editor; she wrote, assigned and edited articles and designed the issue. Tom was the publisher, the frontman, the advertising executive. He also answered the phones, with an “inimitable press room bark: ‘Sq-uash News!’” as Richard Millman remembered. “Whenever you called and Tom answered, you had the sense that the presses were rolling, that the front page couldn’t be held unless the great man himself was to deem an item truly newsworthy.”

One thing, in the Jones way, led to another and with their unique access and attitude they started to change American squash. Their gauge became whether they had annoyed some faction or another, especially an old-guard, old-school type. “We figured we were doing absolutely everything right,” Tom said, “if we were pissing everyone off.”

They found that they could get more advertising if they ran a tournament themselves and secured corporate sponsorship for that tournament. Once in the late 1970s, they had a chance to get Sharif Khan on television to promote a tournament. Sharif, exhausted after a tough match, was reluctant to do the interview. “Well,” Tom said casually, “I’ll just have to cancel the limo they’re sending.” Limo? Calling his bluff, Sharif agreed to go to the studio. Tom, meanwhile, had to scramble to find a limousine company and get a limo to the courts.

Why not go gangbusters and do a portable court one? So they did, to tremendous acclaim. The 1985 North American Open had a total prize-money purse of $75,000; today the equivalent purse would be $155,000. In other words, the Joneses ran the biggest pro singles tournament in U.S. history.

Next came the epochal shift to softball. In 1985 they took on the U.S. Open and converted it from hardball to softball. Again, it started off without fireworks—the first Open was on a twenty-foot-wide converted racquetball court in a now-defunct health club in San Francisco—but with huge impact. The Joneses used point-a-rally scoring in the Open, which was the first time it had been employed in a major softball event; now, a quarter century later, the whole world uses point-a-rally. The following year, in Houston, they lowered the tin to seventeen inches, which became the norm for men’s pro squash. And the year following that, the U.S. Open was on ESPN, the first time pro squash had appeared on a national television broadcast.

In 1989 the Joneses aggregated seven small men’s pro softball events into a “Grand Prix” with corporate sponsorship. The Grand Prix lasted a full, riotous decade; introduced dozens of overseas pros to America (where they ended up residing) and to wearing eye goggles; and brought pro softball squash to more than twenty cities around the nation.

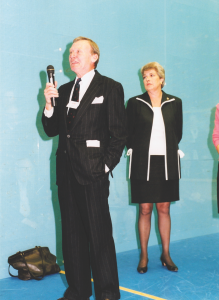

All this pathbreaking led the Joneses to becoming international. Tom was the manager for the U.S. team at the 1991 World Championships in Helsinki and the 1992 Pan-Am Federation Games in Rio. Moreover, they both played a central role in getting squash admitted to the Pan-Am Games and into U.S. Olympic Committee fold. Hazel was the press liaison for squash when it was in the first Pan-Am Games in Argentina in 1995. “It was the best moment,” remembered Hazel, “watching the U.S. team come into the stadium and hear the chanting of “USA! USA! and see Mark Talbott and Alicia McConnell, the culmination of years of work and seeing those great players getting the chance to perform on the international stage.”

The where-are-they-now period started in 1997 when the USSRA dropped Squash News as the member benefit. It was a surprising move, announced awkwardly and for two years afterwards the Jones soldiered on, running tournaments and publishing the magazine. In 1999, they bailed.

They were living in Hope Valley, a hamlet in western Rhode Island. They had moved there in Jones, spur-of-the-moment style, in 1984. Within thirty days of deciding to decamp from Manhattan, they sold their Upper East Side condo and a beach house in Westerly, RI, cancelled the lease on their office in midtown Manhattan and moved into a two-plus acre place on the Wood River. It was a lovely, secluded retreat, three-quarters of an hour from Providence or Newport. “I remember visiting them a lot there,” said Mark Talbott, who also lived in Rhode Island. “We’d boat down the stream, fish there. Very cool place. And downstairs, it was like a printing house, with stacks of magazines, papers everywhere and Tom telling another story.”

After selling Squash News, they bought a local driving range “in a moment of madness,” as Hazel liked to joke. Open from 7am to 10pm, the range had a resident coyote who materialized at twilight around the 150-yard marker. Golfers often asked Hazel for coaching tips and although she had never swung a golf club in her life, she always did. Her advice was always the same: “Don’t try to kill the ball.” Many regulars credited Hazel with improving their game.

But with no employees, the long hours were tough when there was abundant sunshine and after a record 43-day stretch of no rain, Hazel fell and broke her left ankle. They decided to move. Uncharacteristically, they took their time and scouted places everywhere between Virginia and the west coast of Florida. They landed in Hampstead, a village about twenty minutes north and inland of Wilmington. Tom knew about the area because in the mid-1950s while in the Marines and based at Camp Lejeune, he had rented a Wilmington beach house.

They live in a former model home in a new development of three hundred homes, the Highlands at Castle Bay. Tom plays golf on the links course there: “I’m terrible. My handicap? My handicap is my head.” Hazel gardens, especially roses.

Unable to stay away from publishing and advertising completely, they bought a little magazine and turned it into Wilmington Today, a hundred-page plus hardback annual. Chock-a-block with ads and information on the Cape Fear region, it has a circulation of more than 15,000—hotels, beach rentals and doctors’ offices display copies. Wilmington is a vibrant city, with a famous historic district and the childhood home of Michael Jordan. It is also the third-largest film and television industry in the nation: after Los Angeles and New York, Wilmowood is huge and has made films like Blue Velvet, 28 Days and Hounddog and shows like Dawson’s Creek.

Now in their mid-seventies (Tom) and mid-sixties (Hazel), they are happy and content. Hazel brings home a dozen bagels whenever she visits New York, but otherwise they don’t miss the hurly-burly of Manhattan nor the solitude of Hope Valley. In a way, they are at long last following Hazel’s inimitable golf advice: Don’t try to kill the ball.