By Richard Millman, Director of Squash, Kiawah Island Club

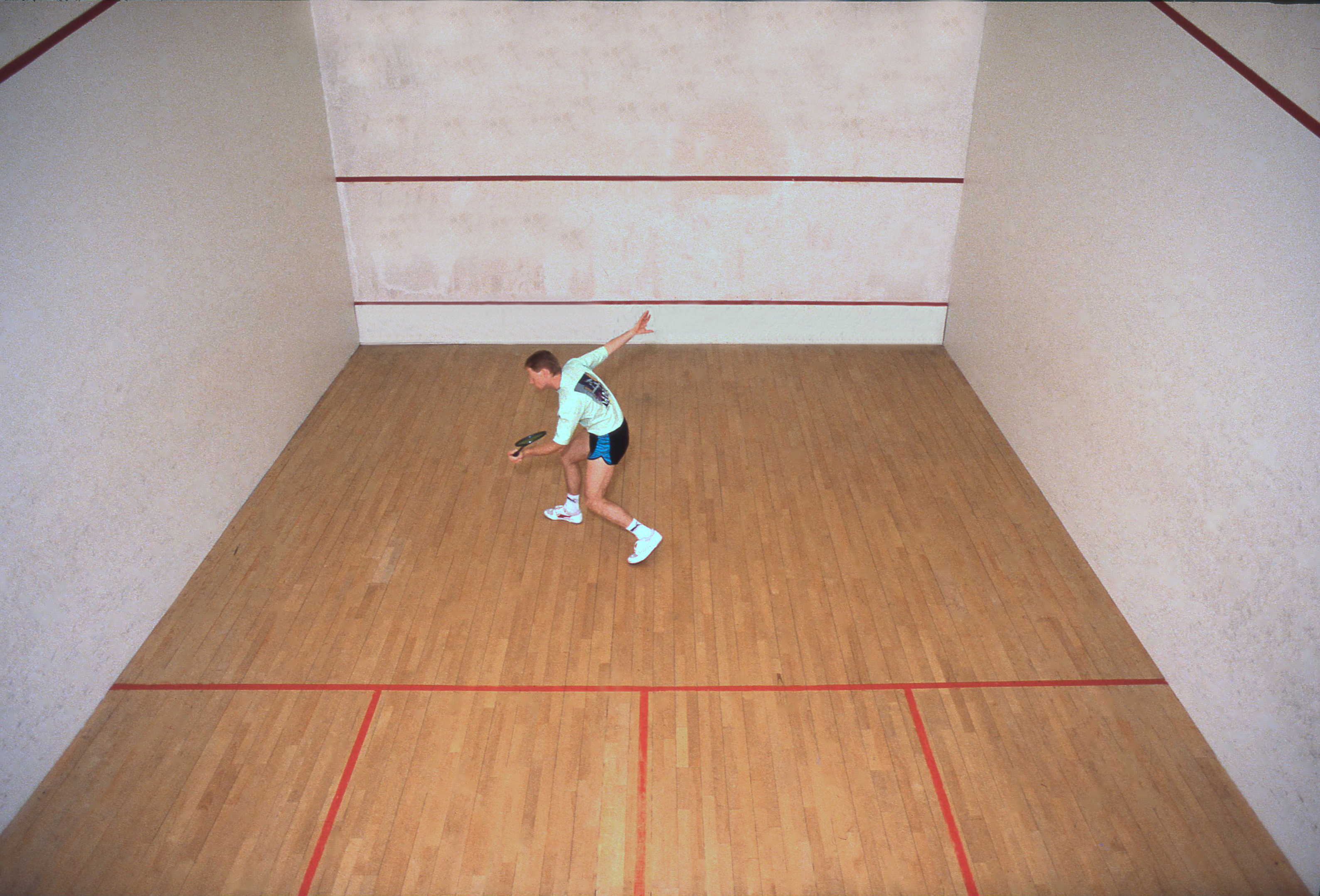

No matter what kind of shape you’re in, you need to be able to move on a squash court in a sport specific manner.

The classic track and field athlete can break records for running in a straight line, but a squash player has to be able to mold their body to the patterns and restrictions of the game.

Ghosting, or Star drills as they are sometimes called, is the best way to train yourself to move efficiently on the Squash court. Once you have developed an efficient movement style, Ghosting is also an excellent system for physical conditioning. Note that I say ‘once you have developed an efficient movement style.’

A common error is to charge into a Ghosting routine as fast as you can, hoping to improve your fitness. While you may improve your fitness this way, you will not improve your efficiency/economy of movement and since (as I have said many times before in this series) Squash is a game about managing time, it doesn’t matter how fit you are, if you are taking twice as many steps/twice as long to cover the ground and get into position.

So how to develop efficiency? Let’s make sure we know what Ghosting is.

Ghosting is any movement pattern that reflects movements that are used in a real game of Squash. It is important that you use a racquet and that the space you use is as close as possible to the size of a Squash court. It doesn’t have to be a Squash court—although that’s the ideal situation, but you could use a basketball floor, a class room, a tennis court, in fact any space that you can draw out an imaginary court. I have often attracted very strange looks from folks at the beach, as I have gone through my Ghosting routine on a court drawn out on the sand!

As you will discern from the fact that you can Ghost anywhere you have an appropriate space, you don’t need a ball. An actual physical ball that is. However, when ghosting, your primary focus must be the ball! What do I mean by this? Well how you relate your movement to the ball is a key element of successful Ghosting. Movement drills that don’t emphasize the ball (such as the so called ‘banana’ curve from the ‘t’ to the front corners) are, though well intentioned, worse than useless in my opinion, as they distract your mind away from the ball toward the arbitrary pattern that you become conditioned to, which may have nothing to do with an actual, individual, ball movement.

The key to all Ghosting is your ability to visualize that ball. And not just at the moment you are hitting your imaginary shot—but throughout the drill. You must ‘see’ the ball go into the front corner, ‘see’ your drop shot, ‘see’ the opponent play the cross-court drop, ‘see’ your next drop, ‘see’ the opponent’s shot go cross-court to the mid court, etcetera, etcetera.

In addition to ‘seeing’ the ball, it is useful to use your racquet as this will help you move to an appropriate distance from the ball you are ‘hitting.’ You can Ghost without a racquet, but your visualization skills need to be very powerful, otherwise you will ingrain the habit of running too close to the ball. If you haven’t got a racquet on vacation, even a stick of the same length as a racquet will help.

Another key aspect of Ghosting is its value in imprinting the court boundaries on your mind. A little bit like a bat’s sonar, you need to have a powerful peripheral sensitivity so that you are constantly aware of your surroundings—namely the walls, your opponent, the spaces available to you on the court and your relationship/proximity to all of these.

While your primary focus must always be the ball, your mind is constantly working at secondary and tertiary levels, gathering information using your peripheral awareness.

Ghosting is the best way of developing this important indirect sensitivity.

There are many possible patterns to use, but the one I recommend that you start with is a six shot pattern.

Starting from the center of the court (or whatever space you have drawn out), move to an imaginary drop in the front right corner, setting yourself up for a counter drop. Decelerate and come to a balanced, set-up position and then, as you start your recovery still leaning toward the ball, play your drop.

As you ‘see’ your opponent play a cross-court drop, you will be half to three-quarters of the way back into position. As your balance has never left the ball, you can now easily change direction in a ‘V’ shaped movement, so that you now move to the front left corner and once again, as you begin recovering into position for the next shot, play your drop.

Your speedy opponent now plays a cross-court width, which, once again keeping your balance toward the ball, you move to cut off on the right hand side wall, intercepting it at the point that the Short line meets the side wall. You set up for a drive, which as you start your recovery into position, you hit straight along the wall. You then see your opponent hit a cross-court to the left side of the court, which you intercept once again at the junction of the Short line with the side wall, once again playing a straight drive along the wall.

Your opponent again intercepts and this time plays a cross-court lob into your right side back corner. You move into position and seeing the ball come off the side wall, then the back wall, you get low and, as you recover into position for the next shot, you play a high float straight down the wall. Your opponent intercepts with a high cross-court volley lob, which lands in your back left hand corner.

Once again keeping your balance toward the ball, you approach, set up, start your recovery and play another high float down the left hand side wall. Your opponent intercepts with a volley-boast into the front right corner, which you move to play…and then repeat the whole sequence.

This pattern, although a slightly strange rally of cross-courts from your opponent, will condition you to a) set up, b) give you a subconscious blueprint of the court so that you instinctively know where you are, c) develop your visualization skills, d) automate your footwork to most efficiently relate your movement to a moving ball, e) condition your expectations so that you can mentally, physically and emotionally connect with the ball and the court, f) develop your peripheral awareness so that you can ‘feel’ what is happening around you.

Once you can execute this drill with balance and poise you can start trying other patterns.

One great idea I heard recently was from my friend Mark Chaloner (the former World No. 7 and chairman of the PSA). He suggested ‘doubling’ each shot in each position so that, for example, in the front right you would play your straight drop and then ‘see’ the opponent play a counter drop back to the same place. By forcing yourself to play twice at each station you will find your change of direction will improve rapidly.

You can also break the patterns into simpler patterns—for instance just the front two corners, or just along the Short line, or the back corners. This is a good idea for speed work—although never forget that Ghosting must not be done at a rate that is faster than you are able to maintain balance.

You can also randomize the sequence—as long as you ‘watch’ the ball at all times.

A popular system is also to number the stations and have someone call out random numbers. I am not a fan of this system, as it takes the focus away from the ball and makes the Ghoster overly focused on the person shouting the numbers.

Once you have the technique down you can then use Ghosting not only as a movement training system, but also as a physical conditioning system.

If you are going to do this I suggest you work with a Sport specific physical trainer—someone like Damon Leedale-Brown, who will explain the physiology and mechanics of the fitness systems you are hoping to train and who will give you a scientifically based training regimen.

You will need to understand the work period, the rest period, the number of repetitions and the rate at which you increase your program.

A very simple system is to Ghost for one minute on and rest for one minute off. Repeat until you feel you could just do one more—then don’t do that last one, so that the next time you train you are excited about building your reps—not fearing the increase.

Other programs include: minute on thirty seconds or even fifteen seconds off, fifteen seconds on and forty five seconds off, two or three minutes on and a minute off.

All of these will train slightly different systems. Make sure you find out what you need specifically and then get help from your sport specific conditioning professional to determine your training program.

Don’t try and go too fast or you will see Stars and you won’t be an effective Ghost!

Next month: Tournaments—How and Why to play them.