By Richard Millman, Director of Squash, Kiawah Island Club

Last month we discussed skills and techniques for getting out of the back corners (Jail).

This month I am going to talk about conditioned games and other measures for avoiding getting stuck there in the first place.

The key to staying out of jail is to take the ball early. There are two main methods here—the volley and the half-volley.

The first of these is the most commonly discussed. The first port of call for a volley discussion is the return of serve. Any decent serve must be cut off with a volley. Ideally the volley should take the ball down the wall on the side you are returning from, although a high lob cross-court can be a good variation to keep the opponent guessing and break their rhythm. Short returns are OK or even good if the serve is weak, but don’t go there unless you have practiced a lot, have real confidence and you can move with your own shot so that you are in position for the opponent’s next shot before they can play it.

A simple practice game that really works is a regular game of squash where the receiver has to volley the return of serve—or they lose the point. This jump starts the brain into the volleying mentality.

A good continuation of this game is the length game (every ball played over the short line), still with the return of serve having to be a volley.

Try and make it a golden rule that you never let a good quality cross-court hit the floor after it hits the sidewall. In other words (at the risk of being repetitious) never let your opponent get away with a shot that strikes the side wall and then the floor—always volley it.

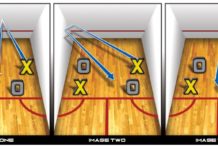

Taking the length game a step further is playing with no back wall. In other words if you let the ball hit the back wall after the bounce, you lose the point. To encourage good length—anyone that strikes a ball that hit’s the back wall without first bouncing on the floor, loses the point.

Play these games PAR-15, or HiHo-9.

Once you become pretty proficient with the length game and have tried the variations, you can move on to a version that really rewards good length and punishes loose balls, while still encouraging you to cut the ball off. In this version, the players must start the rally playing every ball behind the short line. If one player fails to get the ball long, the opponent must attack short. If they make an error attacking short, a let is played; but if they keep the ball up, the player who played short originally must retrieve the ball to a length. If the retriever does get the ball to a length, then the rally continues long until someone fails to get a length again.

This is an exciting game that rewards quality length and forces you to practice attacking short and covering the short ball when you have played a poor length. It requires fairly advanced skill and fitness, so don’t try it until you have mastered the basic length game.

The second of the two ‘cutting off’ shots is the half-volley—a shot played by striking the ball almost at the moment it bounces—sometimes described as “on-the-hop.”

Probably the least taught and most useful shot in retrieving squash, the half-volley should be in the arsenal of any competitive player. The shot is played with a short swing, meeting the ball as it is rising from the bounce. The swing must be timed to start just before the ball bounces, meeting the ball as it comes off the floor. Jonah Barrington used this shot to great effect—calling it a scramble.

The orthodox squash player is conditioned to expect a uniform rhythm and timing to the execution of their strokes. The rhythm of a ground stroke (with the ball bouncing) is different to the rhythm of a volley (without the extra beat of time that the bounce provides). However, most players are so pre-conditioned to just these two rhythmic variations that they neither seek nor understand further subtle variations in the timing of their stroke execution. Rather than decreasing the time it takes to swing—by either making a much smaller swing or meeting the ball as it is rising (instead of the traditional “just-after-the-top-of-the-bounce” timing)—they avoid the situation, fail to cut off the ball and let the ball drop into back corner jail.

To practice your “half-volley,” have a coach or practice partner feed you good length balls, and time your shot to intercept the ball as it comes off the bounce. Have the feeder at the front of the court playing straight down your forehand side wall. You start from the half court line and reach across to intercept the ball. Play a half-volley high to a length and then drop the ball from your own length back to the front to the feeder.

The sequence goes: Player A (feeder) drive to length, Player B (you) half-volley to length, then drop from the half-volley as you recover into position for the next feed.

As you become more proficient, try including the half-volley in the other length and volley drill games I described earlier. With luck you will rarely even flirt with Jail, never mind spending hard time there!

Next month: Do you have Stars in your eyes? Or was it a Ghost? Movement patterns for training.