By Damon Leedale-Brown, Sports Scientist & Conditioning Specialist

Following on from last month when we discussed the importance of strength and mobility for squash, we will now begin to look at effective techniques for improving strength to prevent injury and enhance performance on the squash court.

To identify what exercises are effective in helping us improve strength for the squash court we need to look at our sport. Squash (as with many sports) is not played sitting down; although I am sure there are times in a tough match when the idea of sitting down seems appealing! Squash is played in a dynamic environment with no external support, apart from the occasional use of the wall in desperation or when on the point of collapse! These observations already give us some insight into what may or not be considered effective strength training exercises for squash.

Generally speaking, exercises performed in a seated position will have limited benefit to a squash player (and most athletes), and most machine weight equipment stabilizes the weight for us rather than encouraging us to control and stabilize our own weight. Some will argue that machine weight training is safer than working with free weights. My personal view is that if taught correctly free weight training (in many cases starting with the athlete’s own body weight) is not only safe but will significantly reduce the risk of injuries during competition. Machine weights typically lack proprioceptive feedback (sensory feedback about the position and movement of our body), and lack the need to stabilize the resistance which in turn will more than likely lead to a greater number of injuries in competition. Over the last 16 years of working with athletes and developing strength training programs I cannot remember one injury sustained in training.

Another important element of the sport is that movements and skills performed on court are the result of a number of joints and muscles working in coordination. Strength training should therefore be based on multi joint movements as much as possible (often limited by machine weights which tend to focus on more isolated joint movements). In essence, then, we should primarily perform strength training exercises in standing positions with feet in contact with the ground, avoid the use of machines, and look at developing strength and mobility in full range athletic movements. My approach with squash players has always been to train movements not muscles, and by doing so develop the muscles to work together in a coordinated manner to assist in and control the movements required by a player on court. Essentially the goal of an effective strength program should be to teach a player how to handle their own body weight in movements and positions which are crucial to success in their sport, and gradually improve their ability to perform these movements more consistently, with better control and at higher speeds.

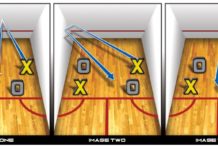

So how do we get started? Start by considering how you move (or would like to move!) around the squash court. What type of positions do you need to get into to feel strong and balanced on the ball? This could include squat-based stances when hitting from deep in the back corners, or stepping out into lunges around the middle and into the front of the court. If you currently do any form of strength training do the movements in your training reflect similar movements you have to do on court?

So how do we get started? Start by considering how you move (or would like to move!) around the squash court. What type of positions do you need to get into to feel strong and balanced on the ball? This could include squat-based stances when hitting from deep in the back corners, or stepping out into lunges around the middle and into the front of the court. If you currently do any form of strength training do the movements in your training reflect similar movements you have to do on court?

Find a space on court (or in the gym) and look at how well you can perform a body weight squat—are you able to do this while maintaining a flat back with your weight through your heels, and lower into a position where the tops of your thighs are level with your knees? Now try a straight lunge—can you step into the lunge without losing balance and collapsing through the hips? Do you finish the lunge with your back erect and shoulders above the hips, and does the knee of the leading leg finish above the ankle? Do you feel balanced and controlled when performing these movements, or uncoordinated and shaky! Even these simple tests will begin to tell you something about your strength to perform fundamental athletic movements through full ranges of motion which should be the starting point in any well-designed strength program.

Next month we will start to introduce examples of exercises (including squats and lunges) that can help develop lower body strength and balance based around the philosophies discussed in this article.