By James Zug

Photos by Jay D. Price/SquashMagazine.com

Like a feather caught in a vortex, Julian Illingworth floats around the squash court with a whirling flash of insouciance. He has the angularity and confidence of a true athlete. He gets to the ball, gets there early, takes it early and takes off back to the T. His ground strokes are great, liquid whips. His overhead volley has an eel-like rhythmic snap as he scissors up to reach the ball. His backhand straight drop is world-class. It has a degree of placement that is genius. He hits it unpredictably. “He’s unafraid to play that shot from anywhere on the court at any time,” said Paul Assaiante, coach of the Trinity men’s squash team. “It’s almost like hardball, shooting from anywhere.”

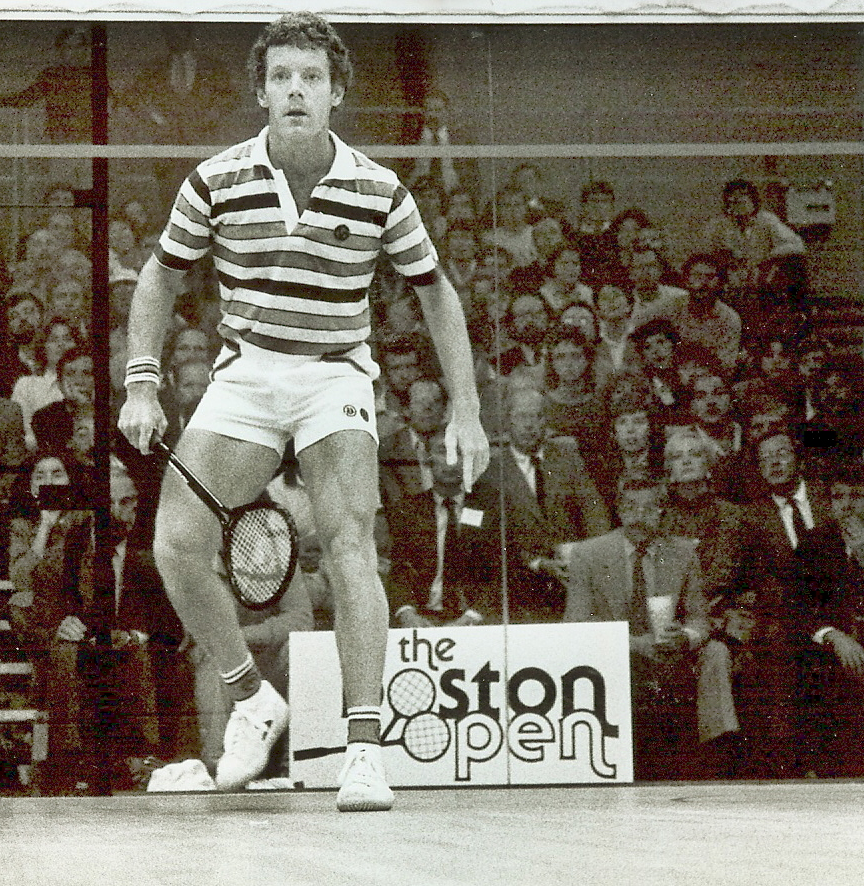

By many accounts—both statistical and observational—Julian Illingworth can now be considered the greatest American male to ever hit a squash ball. He has won five straight national titles, something no other man has ever done. He has almost achieved more on the pro tour than anyone else. He has played in 23 countries. He has beaten top twenty players. He has beaten the World Junior Champion. He has become the face of U.S. Squash.

He knows it all doesn’t mean much. He has an astringent sense of humor. In the summer of 2007, he made a YouTube video for the U.S. Open. In a self-mocking, hilarious piece of guerrilla art titled, “The King of New York,” he went around New York, squash bag double-slung on his shoulders, asking restaurateurs if they wanted to hang a framed and signed celebrity photo of himself on their wall. They all said no. “Squash, what’s squash? Anybody hear of squash?” one of the owners asked. The biggest blow came when one owner gloriously said he was sorry, but he already had a photo of a squash celebrity on his wall. It was Amr Shabana.

Perhaps the truest joke in Illingworth’s video was not the video itself, but the measly number of YouTube viewings: 4,905.

Julian Illingworth is the first national champion since Mark Alger in 1981 to grow up west of the Appalachians. He is a product of the Pacific Northwest. He has McMenamins beer coasters on his coffee table. Though he has not lived there in seven years, his cell phone number still bears an Oregon area code. He’s a Trail Blazers nut. He woke up to Pearl Jam in high school (Black—”I know someday you’ll have a beautiful life, I know you’ll be a star”) and once watched the same Pearl Jam live concert on DVD every night before bed for two weeks while crashing on a friend’s couch in New York.

All of which slightly jars with his roots. His parents are British. They grew up in a remote village near Lake Windermere in the Lake District of northern England. Wainwright is the local icon, not Khan or Talbott or Holleran. They came to the States for grad school and, after a stint at the University of Miami, settled in Portland. Julian’s father is a medical researcher, his mother an eye surgeon nurse. They are an athletic clan—Julian’s older sister has spent most of her post-Middlebury years rock climbing in Yosemite and Asia and has just rafted the Colorado through the Grand Canyon. In the winter.

Today, American squash has a continental reach. The top 100 in the U19 rankings boast boys from 15 states, which is double what it was in mid-1990s when Illingworth’s father introduced seven-year-old Julian to the game. It was just after the Multnomah Athletic Club had converted a couple of hardball courts to softball. His first tournament was a MAC men’s novice draw—”below D” said Illingworth—and he won it. The trophy, made out of stone, weighed almost as much as Illingworth, who was a sprightly mite of a boy at the time. He began training with Asif Mir, under the direction of Mir’s father, Khalid, the Pakistani teaching pro who is something of a minor legend on the West Coast. Mir’s other son, Mohsen, won the 1996 SL Green and soon Illingworth and Asif were the lead horses in Mir’s junior stable.

Isolated in Portland, Illingworth had to get on an airplane to play any legitimate junior matches, and the MAC was very generous in helping fund his forays. First, it was tournaments in Vancouver, Seattle and San Francisco; then at age 11, it was to the heart of the matter—the East Coast. In his first Hunter Lott, he beat Ben Ende 10-9 in the fifth. Soccer claimed his heart at the time, but in seventh grade he broke two bones in his leg during a game and had his leg in a cast for two months. After that, squash was his focus.

At age 15, Illingworth had a growth spurt and emerged much bigger—close to his adult height of six feet—and stronger. In the U15s he was in the top five. He won the U17 Nationals once and the U19s twice. He was clearly very good. At one Nationals at Yale, he was astonishingly dominating, losing just 14 points (British scoring) in the entire tournament, including gobbling up Will Broadbent 0,1,2 in the finals. At age 16, he claimed fifth place in the SL Green, when he shocked Grant Pinnington and Pete Carlin after an opening round loss to Damian Walker. (He came in fifth the next year too.) He also did the usual European junior circuit and finished third in the Scottish Open one year.

The number one American junior in the country and a good student, Illingworth was a prized recruit. It came down to Princeton or Yale. The former had a tremendous team; the latter had a better fit of personality. Illingworth joined a dozen other recruits for a look at Princeton one weekend and decided late one night that it was the right place. Back home, he sealed the envelope with his acceptance. It was a Sunday, so he had to wait until Monday to post it. He called a fellow recruit, Trevor Rees from Greenwich, who was going to Yale. They talked for hours. The next day, Illingworth opened the envelope and changed his answer.

Growing up, Illingworth wanted to be a doctor and so was pre-med freshman year at Yale before bailing out to major in political science; his senior thesis was on relations between the U.S. and the European Union in the Bush years. He lived in Berkeley College. He road tripped to Middletown; his high school girlfriend, Sarah, was at Wesleyan.

He began to see a long-term road with squash. He played on two world junior teams: in Milan when he was 16 and in Chennai when he was 18 and on winter break his freshman year at Yale. “That was the first time, in Milan, that I was aware I could possibly be a pro,” Illingworth said. “I saw the level and saw that I had a decently high ceiling.”

For most top-flight juniors, college is a waste of time squash-wise—training lost to fraternity basements, technique lost to intense challenge matches, passion lost to long practices and longer van rides. For Illingworth, however, it was a fruitful four years. He matured. Having spent a lot of time on his own as a junior in Oregon, he felt comfortable doing solo work and spent hours alone in Payne Whitney. He trained hard with Gareth Webber, Yale’s assistant coach, and for his first two years, had a weekly game with Mark Talbott. “Yale’s approach was that ‘we are going to be the fittest army of robots,’” said Illingworth. There were a lot of four mile runs, eight mile runs, court sprints, weight room sessions and challenge matches so Illingworth’s private morning hit was a necessary supplement.

It is important to note that Illingworth was not a squash grind. He would goof around on the court—in fact, he became friends with Trevor Rees because they spent an hour in between matches playing three-quarter court at the U.S. Junior Olympics in Newport one year. Illingworth was always ready to play one-on-one basketball or a ping-pong marathon. One summer in 2004, he went to New Zealand to train and play PSA tournaments, but other summers he was in Portland playing as much soccer as squash. Many of his core friends were not on the squash team. He was a poker fiend: Texas Hold ‘Em. “It was like his squash,” said Rees. “Jules would always get the best of us. He was patient, he wouldn’t do much, he’d wait for you to mess up and then at the end of the night, you’d look at the table and were like, ‘How did that happen? He’s won everything.’”

College squash was also not easy. Individually, he never won the Intercollegiates. In his four years, he lost to Mike Ferreira and Gustave Detter in the quarters, to Will Broadbent in the semis and to four-time champion, Yasser El Halaby, in the finals. As for the Eli team, the pivotal match came his freshman year in Yale’s dual match against Princeton. The score was 4-all. The place was rocking, the hot-shot freshman gearing up to play his first home match on the glass court and poised to deliver the Bulldogs’ first Ivy League title in a decade. Matched against El Halaby, Illingworth won the first game 9-0. As he came off the court, Yale coach, Dave Talbott, said: “you’ll always win the first game 9-0,” as El Halaby was a notorious slow starter. Illingworth won the second and was up 8-3 in the third. He tinned a forehand drop. El Halaby climbed back in. “He went for his shots and they came off,” Illingworth remembered. Illingworth, lost 9-6 in the fifth. He cried that night. He watched a video of the match more than fifty times, trying to figure out what had gone wrong.

The collapse haunted him—even after he beat El Halaby in subsequent years—all the way until senior year when two things happened. One, he saw El Halaby squander a similar lead in a similar situation (the Atlas Lives match at Trinity in 2006—Gustav Detter with arms raised after beating the unbeatable Princeton Tiger, Yaser El Halaby), although Illingworth thought up until the very last point of the fifth game that Detter would lose and that El Halaby would come back. As the white-sweatered captain of the Yale team, he also reacted strongly to a near loss to Penn. At a team meeting, he broke down and cried, telling his teammates that he desperately wanted that Ivy League title—which the team finally got that season.

“Julian matured a lot at Yale,” said coach, Dave Talbott; “He was a bit undisciplined coming in, relying on his athleticism. Losing to Yasser was gutting, but it taught him that he had to learn how to play points. His senior year, he was one of the best captains I’ve ever had.”

While at Yale, Illingworth became the fifteenth college undergraduate to win the Nationals. He came in seventh at the SL Green as a freshman and lost his sophomore year in the quarters to Jamie Crombie in five. His junior year in 2005, he returned the favor in four in the semis and then overcame Mike Puertas in four in the finals. The breakthrough match came in New Haven the following year. He had never beaten Preston Quick. In his last tournament as an undergraduate on his college courts, he finally beat Quick in a convincing four games in the semis. In the finals, he poleaxed Damian Walker in three easy games. “I knew I could beat the older guys, but Preston was the final barrier,” Illingworth said.

Both Illingworth and classmate, Michelle Quibell, won the Yale award for best college athlete—the first time both awards had gone to squash players. After graduation, Illingworth turned pro. His first overseas trip was nearly his last. After training in Great Britain he went to play four tournaments in New Zealand. They ended badly, with the young pro getting bumped out of the first round three of the four times. Then he flew from Auckland to Budapest for the World University Games. He arrived, after two days of travel, to find that he was not being picked up at the airport as expected. He rented a car and drove three and a half hours into the Hungarian night to get to the tournament venue in Szeged.

For two years he lived a vagabond existence—the U.S. is still one of the few countries with a player ranked in the top 100 that does not substantially support its top pro players. He slept on friends’ couches while playing in tournaments; once, he slept in a hallway because of a communication mishap. He trained with David Pearson, Shaun Moxham and Mike Way, three of the world’s leading coaches, but he always left preferring to work on his game on his own. He gained much needed weight, getting up to 175, about twenty pounds more than in college.

Staying focused through a match occasionally presented a problem. In the 2007 SL Green, he was at home at the MAC and for the first time, his parents and friends would watch him play. A bit nervous before his match in the finals versus Preston Quick, Illingworth found himself down 2-1. He won the next game 11-8. He came off the court and asked his cornermen, Ben Oliner and Gilly Lane, not for advice on how to survive the inevitable Quick onslaught in the fifth, but for the score of the Oregon versus Winthrop NCAA men’s basketball tournament game (for the record, Oregon easily won 75-61 and Illingworth snagged the fifth 11-8).

Recently however, Illingworth has made the National Championship a personal stomping ground. In the course of five matches in Atlanta last year, he lost just one game and an average of a meager 11 points a match. This year in Hartford, he blitzed through all four matches without the loss of a game, losing an average of 17 points a match.

For half a decade, Illingworth has clearly been the lead dog in the U.S. squash sled team. He has played #1 on the U.S. team at the Worlds in 2005 and 2007. In Rio de Janeiro at the 2007 Pan-Am Games, Illingworth beat two higher-ranked players, Canada’s Shahier Razik and Colombia’s Miguel Angel Rodriquez, in the same day (!) to land himself an exhausted spot in the gold medal match. Illingworth succumbed to Eric Galvez, but still claimed the silver medal, the best U.S. men’s result in history. The next day, after a bit of rest, Illingworth knocked off Galvez in the U.S. versus Mexico team match and helped lead the U.S. team to a respectable fifth-place finish.

On the World Tour, the pace was slower. After New Zealand in 2006, Illingworth lost first-round matches in six straight PSA tournaments over the course of half a year. Then he had a breakthrough. At the 2007 Tournament of Champions, he lost in the final round of the qualifiers in a tough five-gamer, but was a lucky loser and faced Dan Jenson in the opening round. He went down 0-2, but then roared back to beat the former world #5 in overtime in the fifth. (He lost in the next round to David Palmer.) That win against Jenson set him up: for the rest of 2007, his PSA win-loss record was over 50%. He got to two finals and trounced Alex Gough, a former top ten player. In New York in 2008, he reprised his Tournament of Champions feat where he again won a first-round match, this time beating Olli Touminen in four, then losing to Wael El Hindi. A few weeks later in Richmond, he won another big tournament match, dispatching Hisham Ashour in four before falling in three very tight games to Ashour’s brother, Ramy.

In early October 2008, Illingworth nabbed another signature win. At Millfield School in England for the Saudi International qualifiers, he hammered Mohamed El Shorbagy, the 17-year-old World Junior Champion, in three straight games. Illingworth thus had a good shot at making the Saudi—the richest tournament in squash history. He saw the glimmer of finally getting a big payday, but crumpled against Joey Barrington, 8-11, 11-9, 11-2, 11-3. Nonetheless, the triumph against El Shorbagy was genuine: it was on El Shorbagy’s home court and the following week El Shorbagy reeled off five straight matches at the World Open, qualifying to reach the quarterfinals.

This year, Illingworth lost meekly to Thierry Lincou at the 2009 Tournament of Champions and then suffered an ugly defeat against a similarly-ranked Tom Richards in Richmond at the North American Open. In a 90-minute marathon, Illingworth gave up the first game and scrambled back from a 2-7 deficit in the second to take the tiebreaker. Up 2-1, he had a 6-3 lead in the fourth. But it fell apart in the end and he lost 12-10 in the fifth. His temper reared its head again in Richmond. In college, Illingworth was known as someone who might occasionally toss a racquet after a tin or moan and curse after a referee made a call against him. These outbursts were not blatant or horrible; they were more a tic that seemed to block his progress. As he began touring, he had tamped it down, but not fully. In Texas Hold ‘Em, it is called “tilting” when you play angrily and sloppily. When Illingworth tilts, he loses.

At age 25, Julian Illingworth is a work in progress, still under construction like his website. He has a masonic devotion to Yale. He wears his college squash team warm-up vest and often his head is seen on court wrapped with the distinctive snip of a towel that belongs to the Eli athletic department. He has settled down a little. He and Sarah, a second-year medical student at Columbia, live together in a walkup on Amsterdam Avenue on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Their one-bedroom is filled with plants and artist prints and exposed brick walls and Craigs-List-found furniture. He plays Guitar Hero. He cooks. He watches films. He trains. He travels. He plays.

How high can he go? In May 2009 he was ranked 35 in the world, his personal best. Can he get above 32, the highest men’s world ranking ever for an American (see accompanying story on Bill Andruss) and into the top 24 to avoid having to qualify for major tournaments? Can he win two more SL Greens to overcome Stanley Pearson’s 86 year-old men’s record? Can he win three more in a row and top Alicia McConnell’s seven straight? Five more to top Demer Holleran’s nine years as national champion?

Maybe then, he’ll get his celebrity photo on the wall of a Manhattan restaurant.

The Answer: Bill Andruss and Softball Squash

By James Zug

Highest world ranking for an American man? When Marty Clark topped out at 59 in 1996, that became the talismanic number that everyone shot for, a number that has now been eclipsed by Julian Illingworth’s 35.

But in my research for my history of squash book, I came across a clipping in the November 1978 issue of Squash News that said Bill Andruss, just back from the world tour, had reached 32 (an editing error transposed that to 34 in the first two editions; in January 1979, Squash News said he had reached 31).

First American, male or female, to go overseas and try the world tour? For years, it has been a mystery and a half dozen people have told me that they considered themselves the first, that they had never heard of anyone going before they had embarked. But it turns out that the first was also the best: Bill Andruss.

Thirty-two in the world and still, more than 30 years later, the only American ever to win a main-draw match at either the British or World Open.

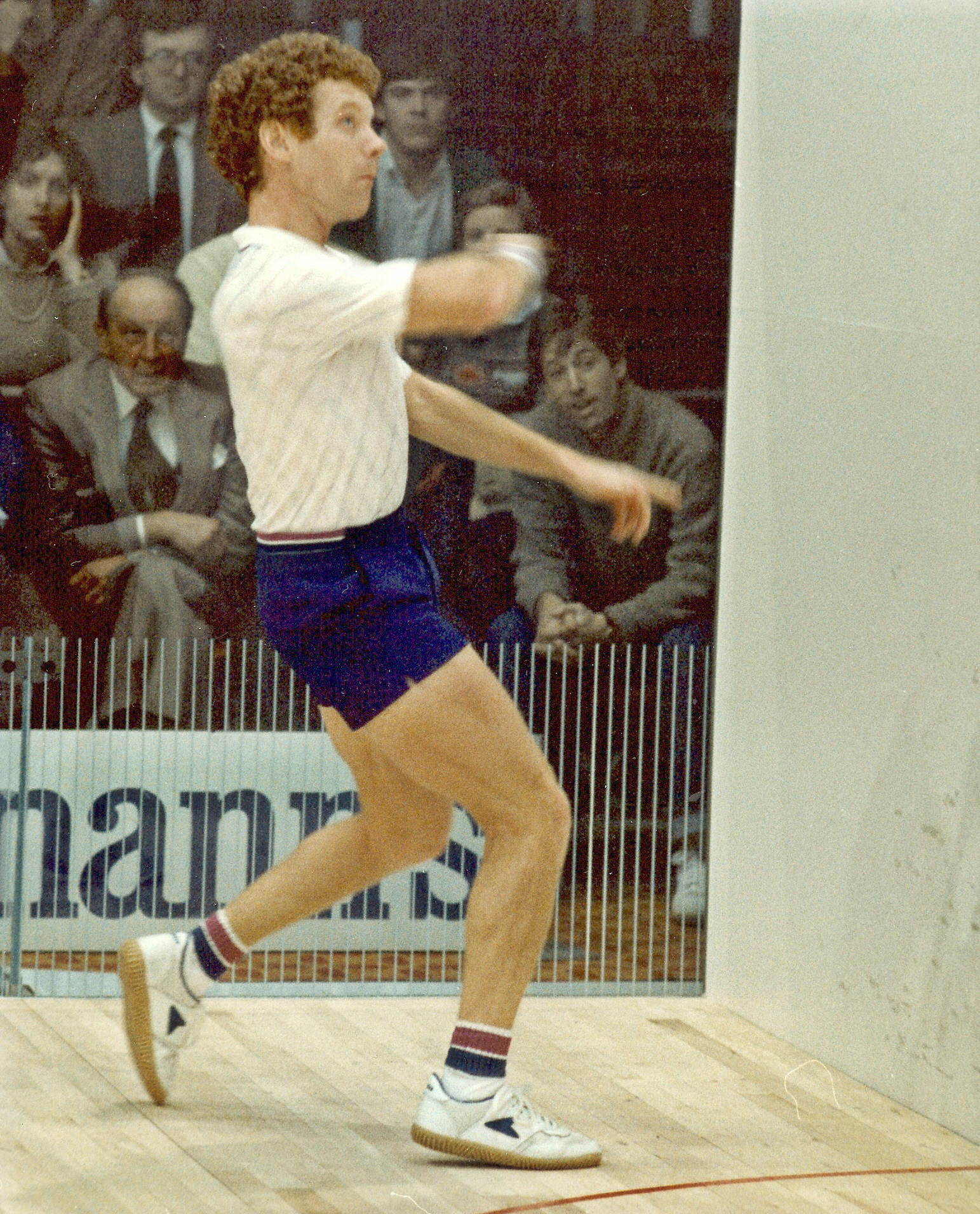

Andruss was more than a footnote. He grew up playing tennis at the Bronxville Field Club and casually picked up squash the winter of his senior year in high school. After a year at Washington & Lee, where he played neither tennis nor squash, he transferred to Fordham back in the Bronx. He introduced himself to his math teacher, Bob Hawthorn, and asked to join the squash team. At that time, Fordham played on five gallery-less courts at St. Joseph’s Seminary in Yonkers, so America’s greatest softballer had a pretty inauspicious learning ground.

But the bantam-sized curly-haired youngster worked hard and skyrocketed up the ladder. His junior year, he was ranked fifth in the intercollegiates; senior year he got to the finals of the intercollegiates, losing in four to defending champion, Juan de Villafranca. Andruss had hopes against de Villafranca, having bludgeoned him 3-0 in the annual University Club of New York winter break tournament.

Softball beckoned. Just days after graduation, Andruss won the 1975 Hyder, beating Stu Goldstein in the finals. “I suddenly saw softball as a game that was worldwide and all year—you could play in the summer,” Andruss said. ”I guess I was getting serious and wanted to give it a try.” So in the fall of 1975, he flew to London.

Through a Rhodesian friend living in New York, Andruss had a single contact: Mike Corby. Luckily, it was the right contact. The former World No. 5, Corby was at the epicenter of English squash. He owned a three-court squash club, the London Bridge Sports Centre, and allowed Andruss to work there part-time while training. For the next two years, London Bridge was Andruss’ base as he traveled around the world giving softball a go.

The tour was in its infancy—Jonah Barrington had birthed the International Squash Players Association in February 1973. Andruss played in two British Opens and two World Opens. In January-February 1976, he qualified through and then beat Neil Topman from Hampshire in three in the opening round before going down to Cam Nancarrow in a respectable 9-5, 9-4, 9-6. “I then watched the other matches, including the Hunt v. Mohibullah final, one of the longest and most exciting in British Open history,” said Andruss. ”Such an education.”

Still an amateur, Andruss played #1 on the U.S. team at the 1976 World Teams (amateur-only) in London. In the individual championships, he beat Phil Mohtadi easily before going down hard to Philip Ayton, the #2 seed. In the team competition, the U.S. came in ninth out of ten teams, only ahead of Kuwait. Part of the blame, according to John Horry, who wrote in Squash Player International, was that Andruss had gotten sick, negating the ”enormous advantage” he had accrued by living in London all year.

Andruss then turned pro and did a second year in London, rooming for a time with Bryan Patterson. Andruss played in Pakistan twice. He was placed in the main draw of the 1977 British Open, but faced Bruce Brownlee of New Zealand, the ninth seed, and lost 3-0. In the 1977 World Open in Australia, he won his first-round match, beating Len Atkins in three before losing to Barrington 9-4, 9-3, 9-1. Andruss still has the Uniroyal World Open warmup in his closet.

Andruss then turned pro and did a second year in London, rooming for a time with Bryan Patterson. Andruss played in Pakistan twice. He was placed in the main draw of the 1977 British Open, but faced Bruce Brownlee of New Zealand, the ninth seed, and lost 3-0. In the 1977 World Open in Australia, he won his first-round match, beating Len Atkins in three before losing to Barrington 9-4, 9-3, 9-1. Andruss still has the Uniroyal World Open warmup in his closet.

By virtue of his second second-round appearance in the World Open, Andruss pushed up his ISPA ranking to 32. Of course, the line immediately is: ”What, were there just 33 guys on the tour?” Well, certainly, the depth of today simply was not there in 1977: here are 325 guys with PSA ranking points right now, three times what there was then. Nonetheless, 42 men entered in the Open qualifiers fighting for 14 spots; 50 more went straight into the main draw.

But the life of a professional in Great Britain was tough. ”There was very little money in making it to the plate finals in Stockton-on-Trees,” Andruss joked. So in 1978, he returned to the States and continued to play. He won the 1979 Hyder (the first year they let professionals enter) and after coaching the 1979 U.S. team (still amateur-only), he led the pro-permitted 1981 squad to its best statistical result ever at the Worlds, finishing seventh out of twenty teams.

He worked as a teaching pro at Squash 1 in Mamaroneck, at Uptown in Manhattan for two years, and then from 1980 to 1984, he worked at the Greenwich Field Club (where he started the WPSA tour stop), before doing a final year at Southport. He played on the hardball tour, reaching a WPSA ranking of eight.

In 1985 at the age of 32, he put down his racquet and walked away. ”It was time to do something different,” he said; ”I didn’t want to look lousy and I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a coach forever. I wanted to leave before it was too late.” He became a real estate agent in the Greenwich area, very successfully.

To this day, he hasn’t played squash since he left. He doesn’t even own a squash racquet. ”Julian Illingworth, never heard of him,” he said when I asked him about the guy likely to better his three-decade-old world ranking and British and World Open records. ”Is he a good player?” he asked