By Richard Millman, Director of Squash, Kiawah Island Club

Continuing with the idea that the student must take ownership of his/her lessons, there are pitfalls to look out for. When modeling or engaging in single executions of a stroke, never let the student look directly at the coach when correcting the stroke. Why? Because a student’s eyes carry their primary level attention. As soon as they avert their attention from the stroke they just played to the coach’s eyes/face, they lose all recollection of the specific motor behavior they just used and transfer all responsibility to the “guru.” If, on the other hand, the student holds their follow-through position and maintains their visual focus towards the spot on the front wall where they hit the ball, they can “listen” to the coach while correcting their technique, at the same time retaining responsibility and control. Most students have been brought up to be very polite and find it difficult to listen to the coach without looking at them in the eye, but it is essential that students are taught this “skill” if they are to take ownership of their own learning and development.

Moving on from the aversion of eyes from the coach, but still driving home “ownership of your lesson,” a second crucial issue is the problem of who it is that is driving the drill. This is a common conflict for students. As a result of reliance on the coach for direction there is a tendency for the student to fall into the role of follower (a concept we discussed last year). This must be avoided at all costs as, in competitive squash, the follower is the loser. We as coaches must teach our students to take advice on board and then use that advice productively and become the driver of the drill rather than the follower.

Only doing as much as is absolutely necessary to satisfy the coach is often not the student’s original intention, but it may become their modus operandi unless we are vigilant. Coaches and students must work to develop behaviors that encourage the student to drive the process. For instance, a very simple behavior that I have found to be valuable is for a student to respond to a stroke or situation that they want to perform better by picking up the ball and saying, “Please, would you feed me that one again Richard? I want to try it again.” This is a great behavior from a student who is not just participating in the learning process, but actually taking responsibility.

Another example is that, in any repetitive drill, the student should be driving the rally/drill by always being in position for the next feed before the coach delivers it. Boast and drive is a classic example where, all too frequently, the coach is the driver of the drill. Students—help yourselves: take control of the rally!

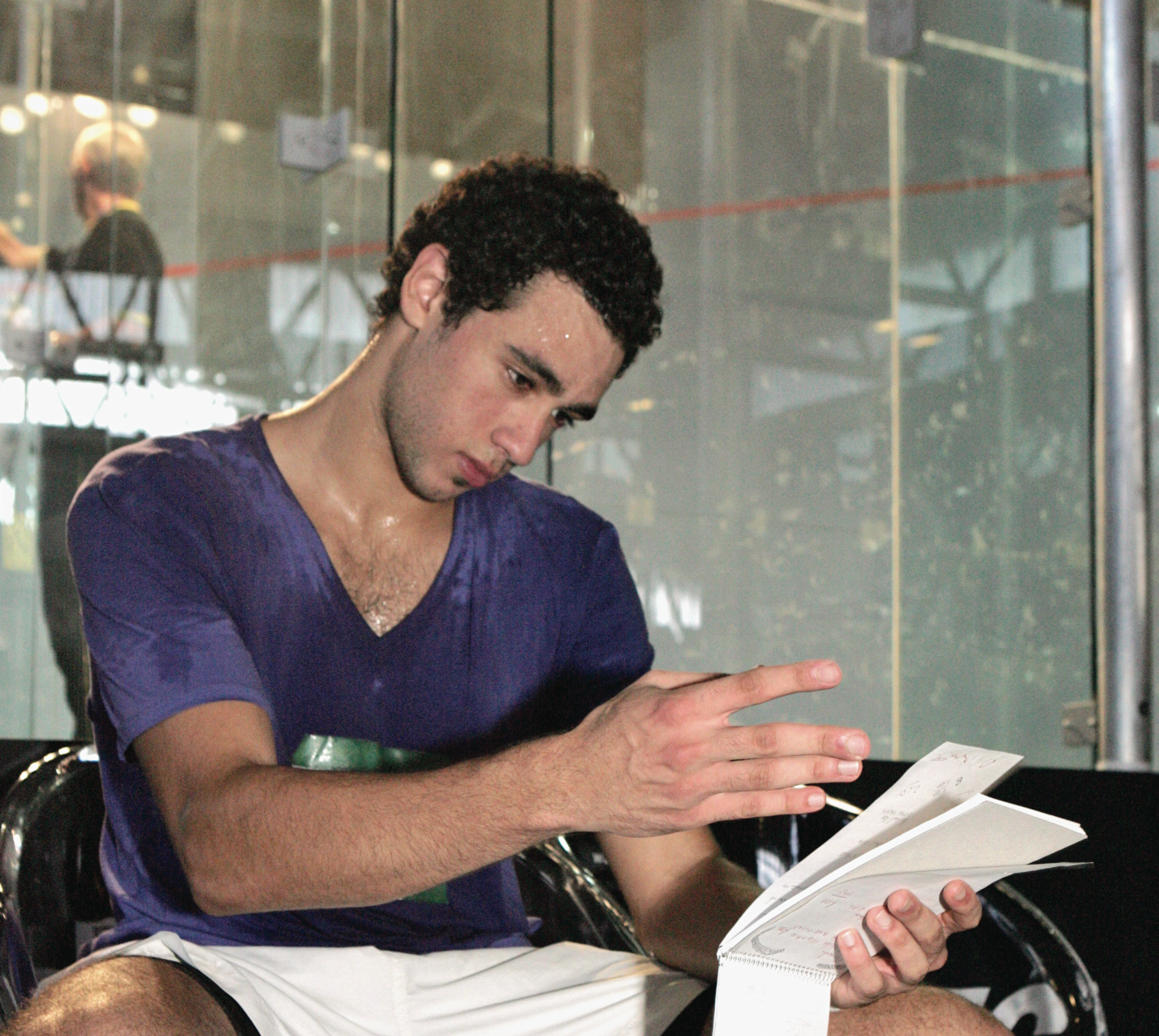

My final advice for the individual lesson and indeed any coaching situation is what I term “writing a shopping list.” At the end of each lesson write down all the key points that you want to take from the lesson in a notebook. Write only in positives—what you want to do better; any key words that the coach gave you that were useful cues or triggers for improved performance. Keep your notebook in a zip-lock bag in your squash bag (you don’t want a soggy shopping list) and re-read your shopping list before each lesson or game. Writing down the shopping list on paper helps to imprint the ideas on your subconscious, and re-reading them regularly helps to automate those behaviors over the long haul. Remember, any new idea or technique will take in the region of 10-12 weeks to automate, and that’s only if you are practicing two or three times a week. The writing part will aid in the automation.

In a perfect world we coaches would operate like teachers and we would know exactly what each student did in their last lesson, but any coach that has spent the day doing 10 or 12 lessons knows this isn’t practical or realistic. However, if the student keeps their notebook of “shopping lists,” both the coach and the student can start the next lesson more productively—if the student re-reads the previous shopping list and arrives on the court armed with that information. This is another example of the student taking ownership of his/her own learning process.

Finally, all too often in junior coaching, parents feel disconnected from the coaching and development process. While some parents are former squash players, many are not and feel helpless in their lack of sports specific knowledge. However, almost every parent is in possession of a veritable mine of unused potential that I believe can be used extremely effectively in the future, provided that it is used in a judicious and sensitive way. Most parents have excellent organizing and planning skills. Put these to work: Make sure that each coach is aware of what the student was working on most recently. Of course you must allow the coach license to determine how they will construct the lesson and what they will work on, and some coaches are particularly sensitive about what might be considered their “editorial control.” But at least if they have the information they can make an informed judgement.

If the student is working with assistants in a general way, make sure they see a Head coach periodically and regularly who can give them a personalized prescription for improvement. Most Head coaches do communicate with their assistants on the program, but if you make sure the information is passed on, there will be no doubts. No one wants to be an overbearing parent and no one wants to alienate either the coach or the child, but do this in a quiet and sensitive way and everyone will benefit. Over the years I have been lucky enough to have had several students that have written everything down from every lesson and even a few that have collated several years of notes in booklet form. I can’t emphasize adequately how beneficial this has been to me in my development both as a student and as a coach of the game.

Next month—Helping your program strengthen, develop and grow.

A Shopping List

1. Take ownership of the lesson—if you want to try something again, ask the coach to feed the same situation again.

2. During the development of form, keep you primary focus on what you are doing—”listen” to the coach’s advice, but don’t look directly at the coach or you will lose track of what you just did and how to adapt it.

3. As a student, drive the drills, practices and games—don’t just do enough to keep up. Keeping up isn’t getting ahead and you need to be ahead to win.

4. Write a “shopping list” of the main learning points of the lesson. And re-read them frequently.

5. Regularly meet with a Head coach who gives you a personalized prescription for your development. Even if you see assistants most frequently, make sure that you are working with one person who is guiding the process.