By James Zug

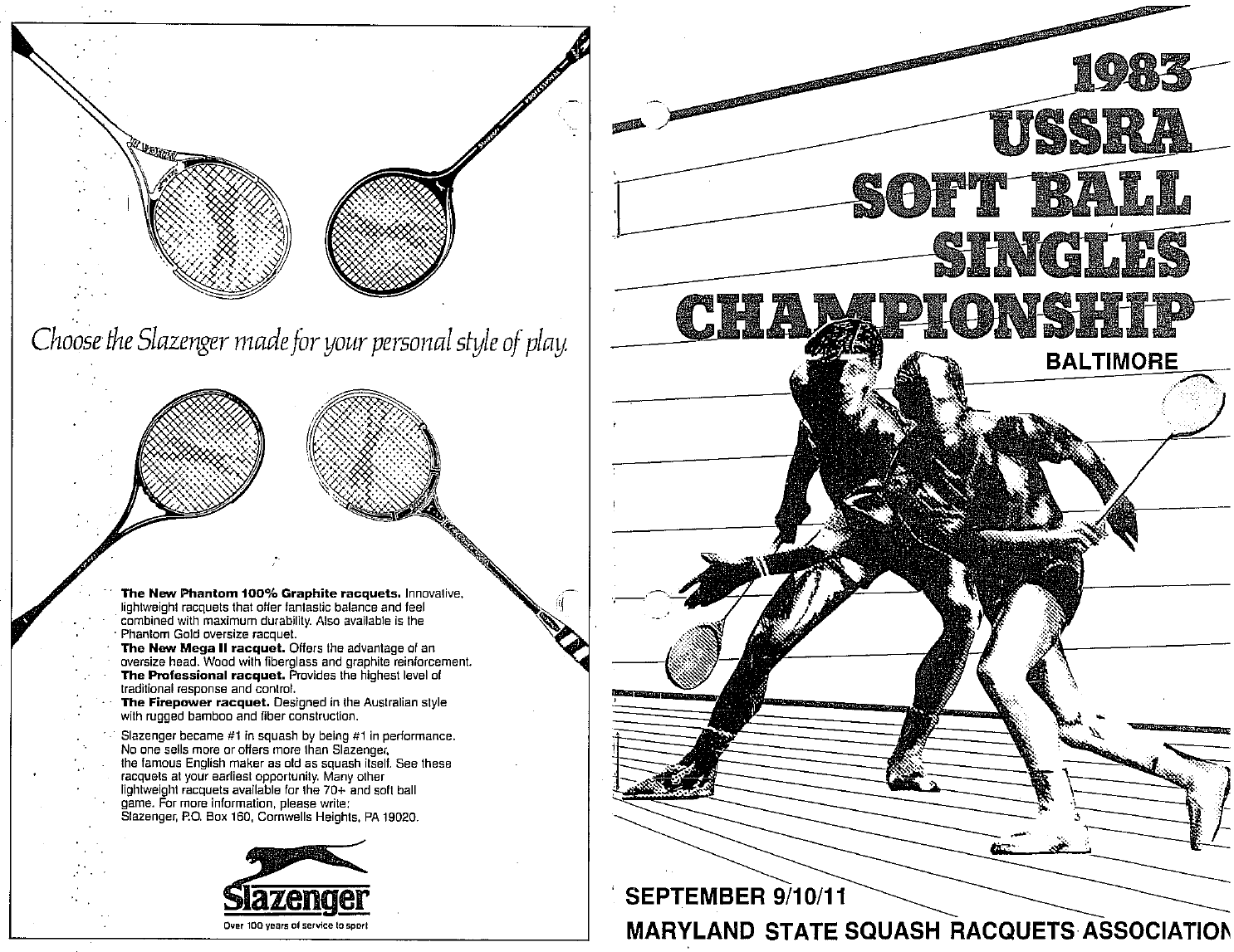

This month is the 25th anniversary of the first U.S. national softball tournament. With the dominance of softball today in America—the mass conversions of the 1990s, the incredible retreat of hardball—it is strange to imagine that the first sanctioned softball nationals was held just a quarter century ago.

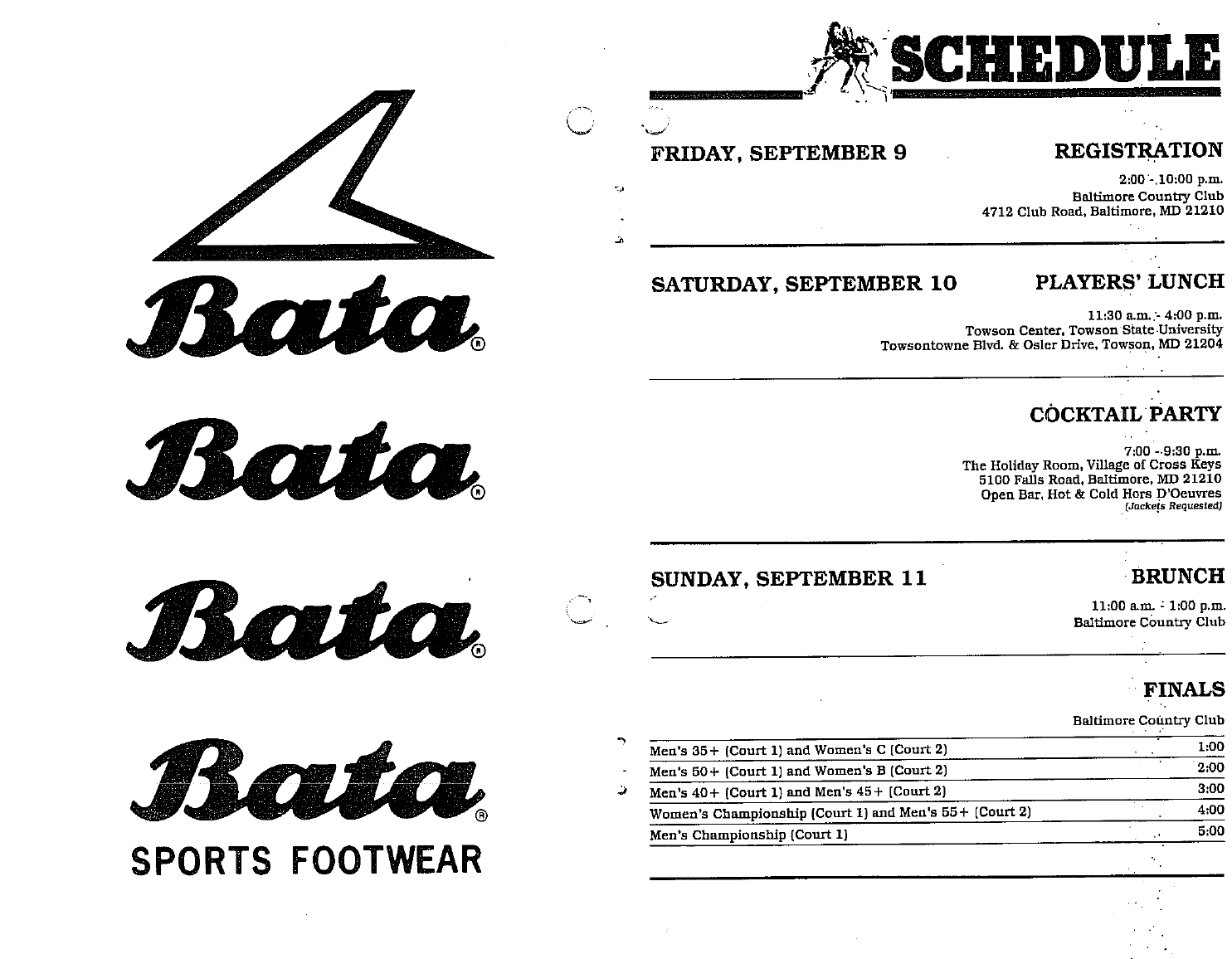

In May 1983, a USSRA ad-hoc committee, chaired by Charlie Perkins, gave a report calling for an official soft ball season (the USSRA in the 1980s called it soft ball rather than softball because, as they wrote, “softball in the U.S.A. is a game played with a bat and large baseball”) from May 1 to August 31, and a national championship in September. On September 9-11, 1983, the Baltimore Country Club hosted the first softball nationals.

Here are the stories of that historic (and hot) tournament and of an era that is now, for better or worse, long long gone.

We studied the situation at great length. I had seen the game in South Africa when I went there on a Jester tour in 1978. Then the next year I played in London at a Jester jubilee. Those were the first times I had seen a softball court. I could tell the game was coming to the States. More and more people were playing—they wanted to play squash in the summer, but no courts were air-conditioned (or heated for that matter) and you really couldn’t play hardball when it was so hot and humid. So softball was the option.

We made the decision to authorize a discrete season, the summer months as when sanctioned softball tournaments could be held. As icing on the cake, at our spring board meeting, we allowed Baltimore to host a national tournament. There were a lot of naysayers, a lot of people who said, “rubbish.” There was a large group of the old guard who fought against it. There were just nine softball courts in the country in 1983. But we said, “Let’s put it on the books and see what happens.” We did it tenderly. We put our foot in the water just to see what the reaction would be.

—Jack Herrick

USSRA president, 1982-84

It was quite a battle. I went to the spring board meeting in New York in 1983, dispatched by the MSSRA [Maryland State Squash Racquets Association] board and proposed that there be a nationals in Baltimore that September. The MSSRA had authorized me to submit the proposal, challenging the board to stage a national championship for the stepchild summer game. There was a lot of resistance. Some guys said that softball had to be played on a 21-foot court, that it wasn’t softball if it was an a 18 1/2 footer (which was all we had in Baltimore). Others said that summer is not squash season or that the age-group classifications were different in the international game or that Maryland had never hosted a major singles tournament. We responded to each objection with: “We will take care of the needs of the players. What harm is it to try it once, since you are so sure that it will fail anyway?”

Reluctantly, the board agreed to allow us our whim.

—Peter Wolff, USSRA Regional Vice President, MSSRA Vice President, 1983 and men’s 45s player

There were a few reasons that we were chosen to host the inaugural softball nationals. First, the MSSRA was one of the first state associations to include a softball title in its championships, in 1977 (we had hosted a number of softball events starting as early as 1973). The softball event was held in August. Paul Deitz, who was MSSRA president in 1980-82, was very keen to make softball an integral part of our tournament schedule. In those days both Mark and David Talbot, both good friends of Paul, lived and played in the area and supported softball.

The USSRA recognized our associations’ commitment to softball. Peter Wolff, who was active on our board, was also chairman of referees for the USSRA. At the annual hardball nationals, the regional reps met to discuss squash issues, and at the 1980 nationals, as I recall, the USSRA had a serious discussion about recognizing softball. Three years later they did.

Both Paul and Bob Hicks, who succeeded Paul as MSSRA president and was also the chair of the BCC squash committee, were totally committed to our hosting the inaugural event. Bob and I, over the two or three year period, stayed involved in every way possible. We wanted this event. Once the decision was made to hold the event, our long-term interest and our experience hosting national championships were enough to get us the tournament.

—Bob Everd, tournament director and men’s 35s player

There was a bit of interest in softball developing around the country in the early 1980s. Hardball was played in the winter and softball was the summer squash activity as a fun, great conditioner. This is why the early softball nationals were played in the summer. It was good fun to have the two versions of squash to provide some variety for those who wished to play squash all year. In Colorado, almost all softball was being played in the summers on narrow courts as the international courts were scarce (we had one in Vail at that time). None of us really understood the game so we exported our hardball tactics to the softball game.

—Marshall Wallach, 40s player

There had been local softball tournaments for years, mostly with expats playing. So Baltimore was the first opportunity for these guys to see how good they really were at a national level. My recollections of Baltimore were mostly that there was the same sense of community like the hardball nationals. Squash appeals to a special breed, thank goodness.

Sanctioning a nationals had been resisted by loyal hardballers. Their most vocal point was that softball would eventually dominate the game. “Just look at Canada,” they said. They were right.

—Charlie Perkins, 50s player and 1985 softball nationals tournament director

What I remember most about the first nationals was how excited the people were that it was being held. A number of softball enthusiasts had been pushing for a separate championship for some time, and some felt it was long overdue. When the first national softball tournament was held in 1983, softball was played primarily as a summer game and I believe tournaments were only sanctioned during the summer months. Although players who had grown up elsewhere played year round, there weren’t all that many of them here at that time.

The number of participants in the first nationals was relatively small but the quality of the field was outstanding. I think holding the tournament was a relatively late decision and it didn’t receive the normal publicity.

—Hazel White Jones

editor Squash News

I remember training for the nationals in Newport. I walked onto the court one day and there were all these funny lines on the side walls and floor and some cardboard above the tin on the front wall. “What’s this about?” I thought Mr. Jernigan was trying to express his artistic side, but instead he was just trying to help us visualize what a proper softball court looked like, to help us transition to the game. Of course, Kenton probably didn’t need the simulation effects, as he was so good at softball.

—J.D. Cregan, men’s A player

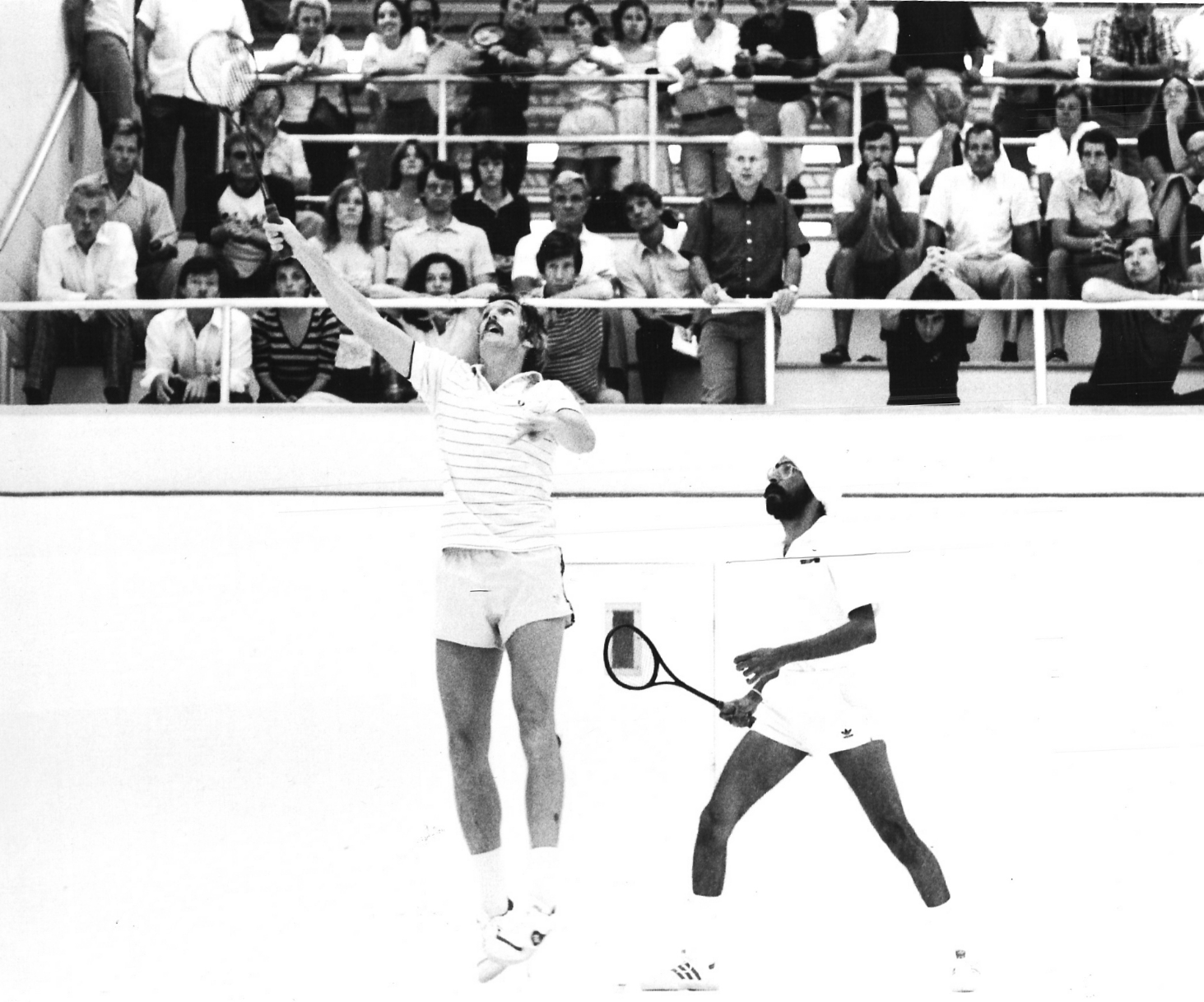

The men’s A was amateur only at the time, and was won by Kenton Jernigan who was hardball champion. If memory serves, Kenton did one of his magic acts—he was down 0-2 in games and a bunch of points before outplaying Gil Mateer. I always thought that Kenton was the most exciting player to

watch when he was behind in a match—even from 9-14 down in the fifth not only could you not count him out, but he continued to hit absolutely amazing, imaginative shots. He was a really creative shotmaker and absolutely fearless, which produced some tremendously exciting matches.

—Hazel White Jones

In the late 70s and early 80s US squash players had very limited exposure to softball. My exposure was limited to occasional participation at the Hyder Cup in NYC and two overseas trips. The first was in 1976 when I was the last person added to join Tom Page, Peter Briggs and Billy Andruss on the U.S. team at the Worlds in England; the second was three years later in the 1979 Worlds in Australia, with Ned Edwards, Jon Foster and Mark Alger. This was a very different situation than the first team I played with in that there was a significant amount of preparation for us to get ready for the competition and we trained for a month at Uptown in New York with Angela Smith. After training, we did a four-week tour of South Africa and Zimbabwe before our stint in Australia.

Getting ready for the first US Softball Nationals was limited to playing on hardball (narrow) courts due to the fact that the Baltimore Country Club’s courts were narrow. In addition to running star drills, I practiced at that time with David Proctor from Canada. David had more exposure to softball squash because Canada had begun the process of converting to the game prior to the US. In addition to the practice that I got with Dave, he knew the Canadians that were coming to the tournament—and specifically he knew how good Richard Jackson was.

This small bit of info was a significant help to me coming out of the gates quickly in our semifinal match against Richard. In the semis and final the court was hot, no A/C , the ball skidding, and I don’t remember complaints from Kenton or Richard—we all just had to deal with it. Another issue that we had to deal with was playing multiple softball matches on the same day, and the semis and finals on Sunday was how tournaments were run.

I forget whether the final was four or five games, but the game prior to the last game, I did not compete well due to my inability to deal with the length of the points and heat. Kenton’s prep for the nationals wasn’t extensive (I believe), but I think he played in a softball event at his dad’s club in Newport.

—Gil Mateer, men’s A finalist

Softball barely existed back then. I trained in Newport with Mike Georgy, Greg Zaff and Billy Doyle, playing softball just to mix it up and to play in the warmer months, since it was ridiculous to try to play hardball on a hot and humid day in July.

In the finals, I had a comeback against Gil. I had a tendency to get down and then come back. I don’t recall Gil failing apart at all, but it was hot and we moved courts since the walls were very slippery, and I think the heat and the long points affected him more towards the end of the match.

It felt like a hardball tournament: same people, same clubs, same narrow courts and same style—I am sure I was hitting the ball a foot above the tin and hitting it as hard as I could.

—Kenton Jernigan, men’s A winner

We pushed off on a hot, steamy weekend from Hartford, Michael Georgy, Nina Porter and me. Georgy was always threatening to drop out of Trinity and join the hardball tour, but since he was born and raised in Cairo, he had softball blood in him and was ready to take no prisoners in Baltimore. But he lost in the second round to Rob Hill. Nina did well and got to the finals. I thought that my conditioning would help me make a large dent in the draw. Not to happen. In my second match, Gil Mateer badly beat me. I was thinking that this guy’s going to play hard-nosed hardball on this hardball court and I was going to play hard-nosed softball instead. Turned out, Gil would have won the match on either court with either ball. Amongst our little group down in Baltimore, the best hardball players were still the best softball players.

The other fond memory I have is that we got a Maryland crab figurine in our player package. For the past 25 years it has sat on my bookshelf in my room in Newport.

—J.D. Cregan

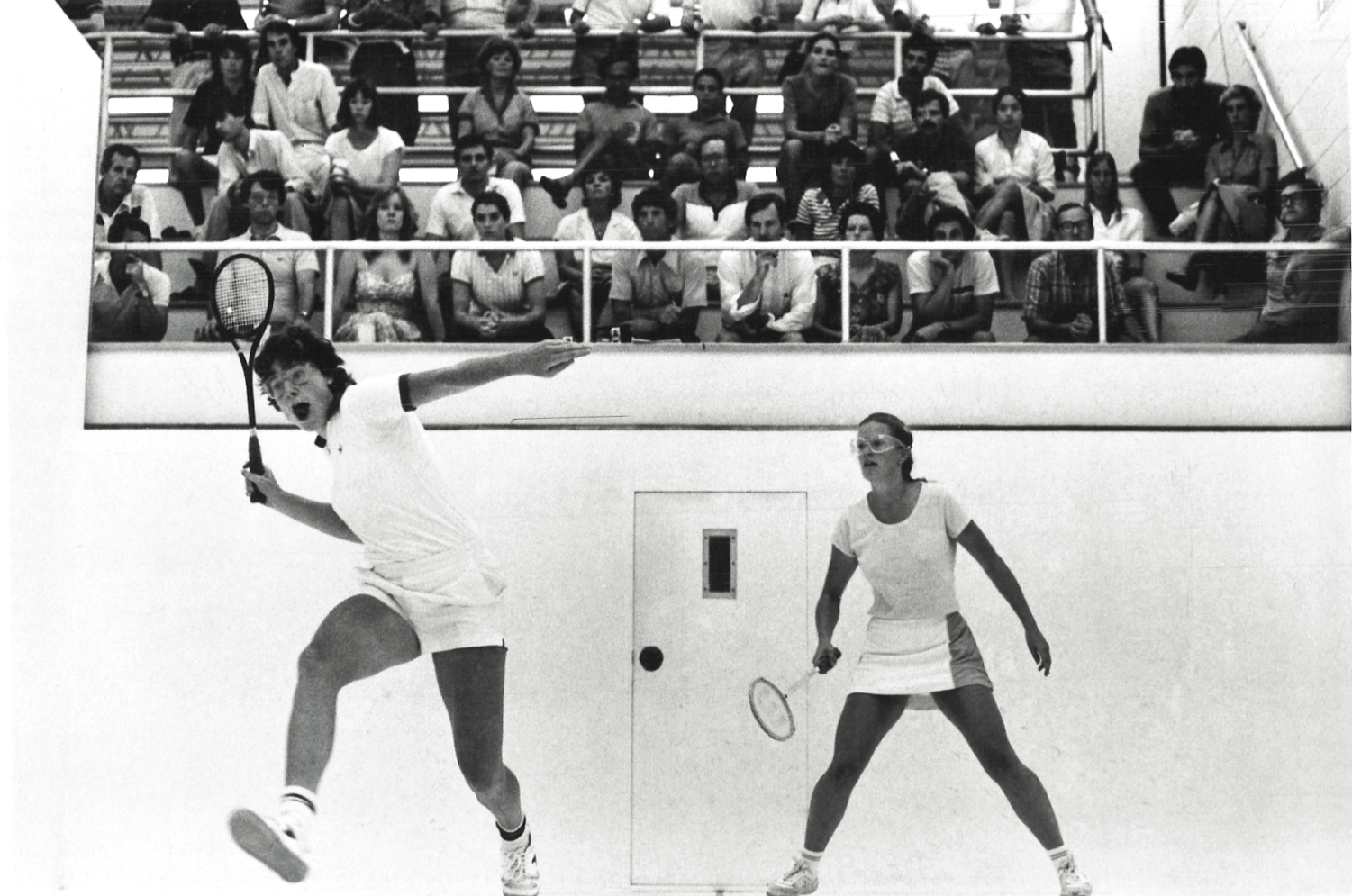

I was excited because Dale Philippi Walker, my coach at Yale, had ingrained in us that softball was a better game for women than hardball since it called for conditioning and stamina even more than firepower. Hardball was a men’s game. That’s why, the previous year, she had stopped hardball training in the middle of the season (early December) and had us start playing this other game that the rest of the world played.

Dale took us on tour to Canada over Christmas break to learn how the game was played. We did come back from that Canadian tour (where we got to watch members of the Canadian national team do unimaginable things and play out points longer than we had ever dreamed of) more fit and with a better understanding of squash in general. Having completed my first year out of college when the softball nationals came up, it felt as though this was what I had been preparing for. I remember driving down in my VW Rabbit after work and the drive from NYC to Baltimore seemed SO long. Being a New Yorker, who didn’t get a driver’s license until I was in college, it was probably the first time I had ever driven the New Jersey Turnpike by myself.

I remember the club was beautiful, awesome and awe-inspiring and the tournament committee very gracious—southern hospitality in style. I think they served crabs or crab cakes at a lovely players’ reception Saturday night.

—Natalie Yates, women’s B finalist

It was hot and a very long match in the finals. I didn’t have any expectations and I didn’t have a kill shot—still don’t—so I relied on fitness. Luck is always welcomed. In the fourth game I was down and repeated to myself: “Take one point at a time.” That really clears the mind of past points, stupid shots and sundry irritations. One point at a time gives each point a fresh start.

I don’t know if it was this tournament, but I remember beating Natalie in the finals and the perk for the winner was being flown to San Francisco for the nationals. I recall Natalie’s boyfriend and his dismay that he would not be able to propose to Natalie on Golden Gate Bridge. Ouch. I knew, but did Natalie?

—Nunzie Gould, women’s B winner

Before I started playing (if you can call it that) squash in mid-1981, I had never played any racquet sports at all. I played field hockey, basketball (at 5’ 1 3/4”!) and lacrosse, all team sports, so trying to play an individual sport with a racquet was incredibly frustrating, to say the least. I remember that my opponent, Laurie Stieff, was absolutely lovely on the court. It seemed to me that the harder I tried, though not getting any better at all in the match and probably actually worse, the nicer she was. She really tried to make me feel better, but I really felt just terrible. This was a harbinger of things to come for me, since learning the game came slowly to me. Were I to have it to do all over again I would take tons of lessons from the very beginning.

—Mac Brand, women’s B player

My (and many other’s) overwhelming memory about the first softball nationals was about the heat that weekend. I believe the temperature on the Sunday when finals were played was close to 100 degrees. I believe it’s the hottest I’ve ever felt playing a squash match. Some of the early Bermuda softball tournaments, played over the Columbus Day holiday weekend, were very hot because of the humidity. But Baltimore was the toughest.

I played in the 40+ division. My opponent in the finals was Denis Bourke—the so-called Lenny & Denny Show. Denis was living in Boston at the time (strangely, he’s now living in Baltimore) and an avid squash player playing out of the T & R. We used to play all the time. He was a very good hardball player, but his real forte was softball. He loved it, and he couldn’t wait until late spring when many of us Boston players would switch to softball until the fall. We had been doing that for many years before 1983, and when the softball nationals began, it was a natural for us to go.

We had a terrific match in the finals. I believe it went four games, with the final one ending 10-8. Needless to say, I was delighted not to go to a fifth. We were both pretty spent at the end.

I did play in several other softball nationals, but this was the only one I won. I met Jay Nelson in at least two other finals, and despite chances to win each of those matches, I couldn’t beat Jay in softball. Then again, neither can anyone else.

—Len Bernheimer, men’s 40s winner

The weekend was hot and humid. At the time I was a bachelor and had invited a female companion along for the weekend and then some sailing on the Chesapeake. In my second-round match, I was the underdog but found myself up 2-0 against Denis Bourke, probably as a result of Denis being a natural slow starter, being over-served the night before and playing in the stifling heat. During the break before game three, my companion came down from the gallery and in a loud voice—Denis was toweling off nearby—said, “Now you’ve got him!” This was all Denis needed to shift into a higher gear and he won the next three games 9-0, 3 and 1, thus permitting me a quick departure from Baltimore.

Out of the Chesapeake a day later, we ran aground.

—Marshall Wallach

By virtue of being a good hardball player, I was seeded number one in the 50s. Softball was a new game to me. I drove down Saturday morning, played Tom Harrington, a farmer from Nebraska, lost three very quick games and was back on the highway an hour later. When I got home, Brigette said, “What are you doing home?” I said, “Well, I lost.” It was the only softball tournament I’ve ever played in.

—Bill Wilson, men’s 50s player

I believe I was knocked out in the first round. It was the era of the 70+ which had replaced the old hardball that had been in use for decades. The Canadians had already moved to softball. In 1977 they had staged the World Amateur in Toronto in a club with, I think, eight wide courts. I attended the tournament as a spectator and it was a wonderful experience. The American Old Guard was still resisting, and the 70+ was supposed to be the answer. Certainly some of the softball shots could be played with it. However the eastern college courts were still all narrow. The “accepted truth” was that neither game was any good on the wrong size court and the cost of conversion was deemed too expensive.

—Bob Frater, men’s 50s player

We worked very carefully on the rules. I was on the phone with the USSRA, making sure we knew what we were doing. The big difference was that there were a lot more let points or strokes in softball than hardball, so that was something we had to instantly adapt to. I knew softball a bit. I had won the Hyder 35s, but I couldn’t play in the tournament because my back went out again—I had had three back operations in the previous years.

—Jim Hense, head referee

I had some exposure to the softball, mainly when I played on the women’s US team in the 1981 women’s world team & individual championships in Canada. During the summer of 1981, I traveled in a motor home with Mark Talbot from Atlanta to Calgary. We did a lot of running and practicing softball when we went through Denver (visiting Sam Khan). In Canada, Mark ran in some road races with a man from New Zealand named Murray Lilley. Somehow we ended up in Toronto and played a lot more of the softball there. It definitely helped me improve my softball skills. At home in Wilmington, Delaware, I practiced softball regularly with Gretchen Spruance—she and I had some real battles.

The ‘83 softball nationals was a small draw, and I was happy to reach the finals after only having to play two rounds. Historically, if I made it to the finals of an event against Alicia (McConnell), it was always a battle for me to get there, and I would feel a bit tired—where for Alicia, it was just another round. But even with a small draw, Alicia’s strength, speed and ball control was superior to mine. She was in a class by herself, and the rest of us top women players knew it, yet we did our best to see how well we could fare against her.

During the 1981 world champs, Alicia won the junior event for her age group. I’ll never forget watching her in the finals of that event. It was pure Alicia. She was lean, moving exceptionally well and totally focused. I was sitting in the gallery next to Brad Desaulniers, and it occurred to me that a boy was actually watching and was impressed by a girl player.

Alicia was just amazing. I remember being sixteen and my younger sister Sophie and I signed up for a squash camp in Newport, Rhode Island. (We were housed by the Jernigan family, in an upstairs boy’s room that had a pet tarantula.) Alicia was also at that camp, Paul Assaiante was the training coach and had us do long, slow distance runs, and Alicia kept right up with the strongest of the boys. One afternoon a bunch of us kids (Kenton, Jimmy Martin, Oliver, J.D. Cregan) went swimming in the ocean and the waves were rough. I couldn’t believe how Alicia was fearless and cut through the waves with no problem.

—Nina Porter Winfield

finalist women’s A

I came to the first nationals because it was close to home in New York, didn’t cost much money and most of all because it was the first one. We wanted to see would happen.

—Alicia McConnell

winner women’s A

The women’s A was won by Alicia McConnell, in my opinion the U.S.’s best female player ever. Alicia completely outplayed Nina Porter, and I think won in almost no time and in three very one-sided games. Alicia played only in the inaugural softball championships, but won seven hardball titles in a row before she stopped competing in 1988. In 1995, she not only played her way onto the Pan-Am team, but beat Ellie Pierce, the women’s open titleholder at the time, which I thought was an amazing feat.

—Hazel White Jones

I had played very little international squash and was really hammered in the second round by George Morfitt, with whom I was competitive in hardball. Bob Everd and Peter Wolff did of good job of running the event and David Carr was able to build on it and produce a first class tournament in Washington in 1984.

The USSRA and its sanction of a national softball tournament had a negligible effect on the growth of soft ball. The USSRA was behind the curve—softball was already happening throughout the country, even in the Northeast. Local SRAs, after holding summer softball leagues, found that players were unwilling to return to hardball in the winter. Softball was a grassroots phenomenon that the USSRA was powerless to control, and they found themselves presiding over the extinction of the great game that they loved.

—Tom Jones, publisher Squash News and men’s 45s player

Since we had quality people, things fell into place pretty well. I am sure there were areas of concern at the time, but today I don’t remember any that created panic—with one exception.

That one exception was the weather. That weekend was extremely hot and very humid. The humidity was the real culprit. In those days none of the courts were heated in the winter let alone air conditioned for summer. By finish of play on Friday night we were scrambling for fan rentals; in those days there weren’t portable air conditioning units to rent. By early Saturday morning we had fans in every gallery, both human and mechanical. Play was interrupted as often as necessary for safety while the court floors and walls were toweled down.

We had certified local referees for every match starting Saturday morning. We chose not to have winner or loser ref. In the year prior we insisted on a number of the better local players becoming certified refs. Peter and Jimmy Hense were instrumental in assigning properly qualified refs to those matches that were likely—how can I say—to be challenging.

There were two stories that I remember. One was a player from Texas who wore cowboy boots and chain smoked. No sooner than his match was over he lit up. I don’t think I ever saw him without a cigarette and he never seemed to tire on the court.

The other involved two players, neither name can I remember. Just two players entered the 60+. We put them in opposite halves of the 55+ draw, and I saw to it that if they each lost their first round that they would meet in the consos. They played their match in the far corner court of the Maryland Club. Watching the match were one of the player’s wives and me as the ref. It went four games, at least one in overtime. Both were exhausted; I was ecstatic. To see them play in those conditions and at that age (which I have now blown past) stays with me to this day. I knew then that, injuries aside, I would stay with this singles game if for no other reason than my health. At the Saturday night dinner dance I took a few minutes to recognize this match. Since the USSRA did not sanction the 60+ flight, the MSSRA gave them trophies and unofficially recognized them as the winner and finalist of the first USSRA 60+ national championships.

—Bob Everd

All the matches were played on hardball courts and with typical Baltimore September weather, the ball was lively for sure. Everyone who competed had a good time and I think they all felt glad to be recognized.

I don’t think the USSRA really had a handle on what was happening around the country, and how many people wanted to see the game grow beyond its traditional boundaries, both socially and economically. This is all hindsight and I’m not sure that I was even aware at the time that the people the USSRA spoke with were all like-minded. Most of the officers in the various district associations were people who came from the boarding school, private (mostly men’s) clubs backgrounds and they were not particularly thrilled that squash was being discovered by a different group of people. As softball grew in this country, as the intercollegiates and junior players switched exclusively to the international game and as we began to focus on improving the visibility of the sport by getting into the regional Olympic competitions (Pan American, Commonwealth, Asian Games, etc.), the chasm between the primarily older hardball players and the younger softball players grew. Fred Weymuller, by the way, talked to me way back in the late-70s about teaching juniors to play with the softball, because the game was so much easier to learn. He wanted to write a column for Squash News telling others why it made sense. I remember saying that I thought that idea was crazy and wouldn’t accept the article. He was absolutely right, of course. It just took nearly a decade or so for others to come to the same conclusion.

—Hazel White Jones

It was exciting creating something new; a sense of change. We were proud to be a part of the first one. Everyone was pumped seeing history being made. For years after, you’d see guys wearing the tournament shirt, that subtle hint of pride at having played in the first one.

—Jim Hense

It was such a hot weekend—the hottest weekend of a hot summer. And it was a great weekend, 118 players, great fun. Since we had a year’s time, we knew that we could really make an even better event in DC the following year and we did—204 players, a band that played well past midnight, huge fun. So the foundation of Baltimore—the fact that they did such an amazing event on such a short notice—was essential in building up the softball nationals.

—David Carr, men’s A quarterfinalist and 1984 softball nationals tournament director

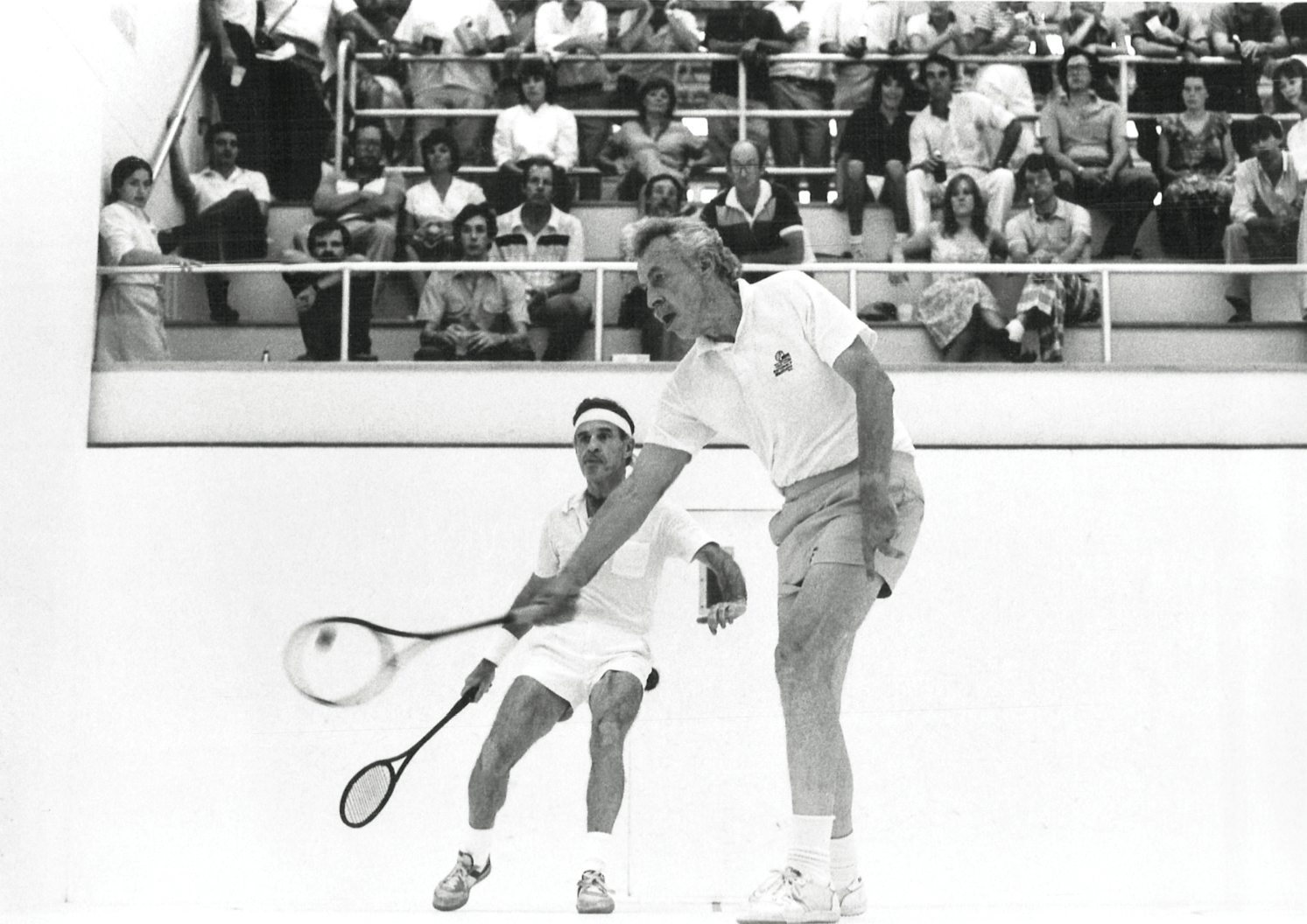

The weekend was great. We held our fall USSRA board meeting there (and decided to mandate that everyone wear eye goggles in all tournament play, another historic decision). It was so hot. I remember Darwin (Kingsley) moving the men’s A finals after the second game to another court, the walls were so coated with moisture.

The first nationals instantly validated the idea that squash was a 12-month sport, something you could do all year round. Would you have predicted that in just 25 years hardball would be all but gone? No, but we left Baltimore knowing that something big had just happened.

—Jack Herrick