By James Zug

On a bright, cloudless summer day, Mark Talbott is rushing to the Palo Alto train station to pick me up. He is late. He has borrowed a car from one of his Stanford squash players—the Talbotts are a one-car family—and the exchange took longer than it might have, mostly because Talbott is notoriously copacetic, unrushed, a good listener, warm.

Everyone is his friend. His players joke that at introductions before dual matches, they wait with bated breath for the moment he says, “This is Coach X, a very good friend of mine.”

Eventually, Talbott pulls up to the train station. He hops out, gives me a long handshake, a laugh. He asks about my family. He thanks me for coming to interview him. We drive off and for the next six hours he gives me a tour of the Farm, as Stanford’s eight thousand-acre campus is called. He praises the architecture (especially the cathedral) and details some of the history of the school’s legendary sports teams (swimming, tennis). The eucalyptus trees and the streaming gaggles of bicycles make the scene complete.

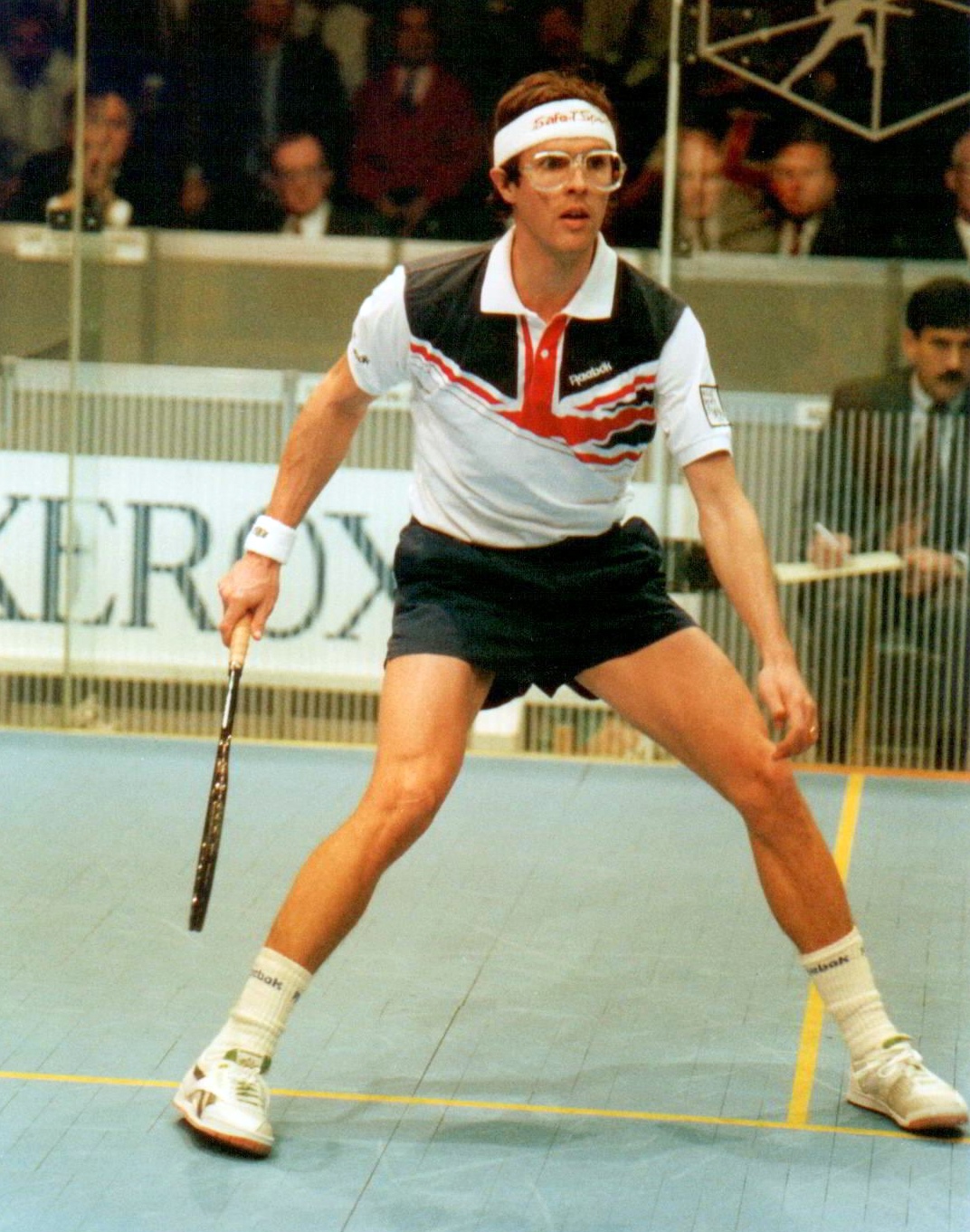

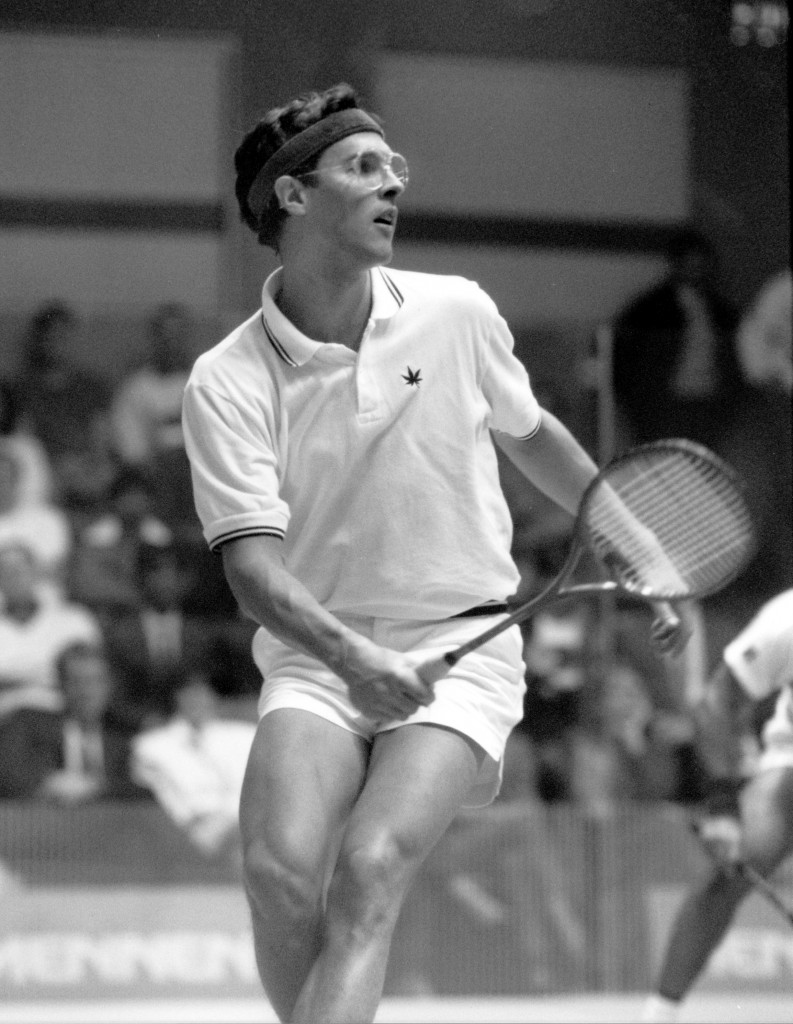

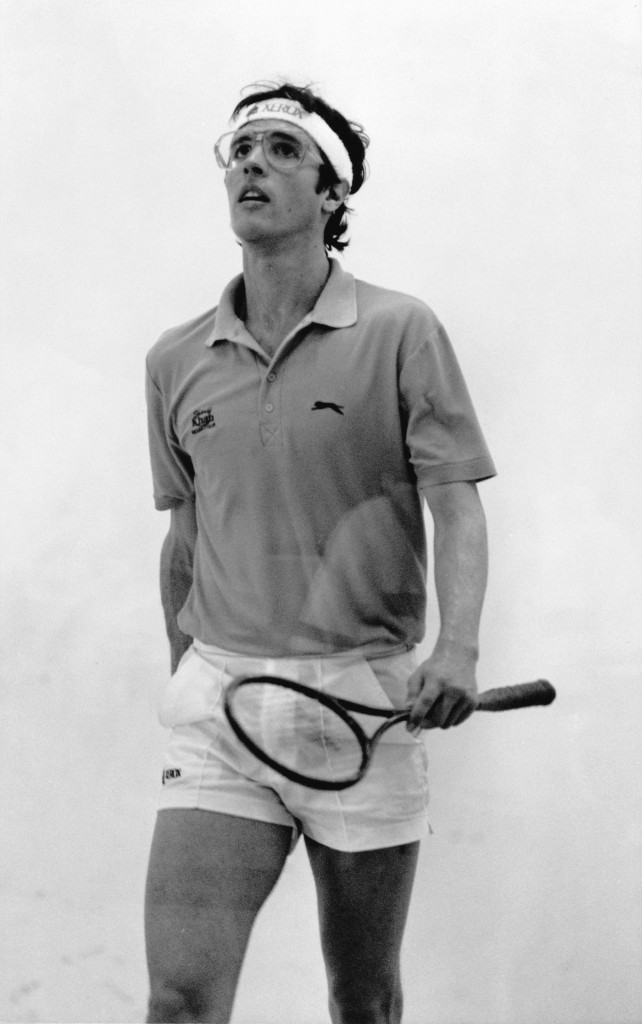

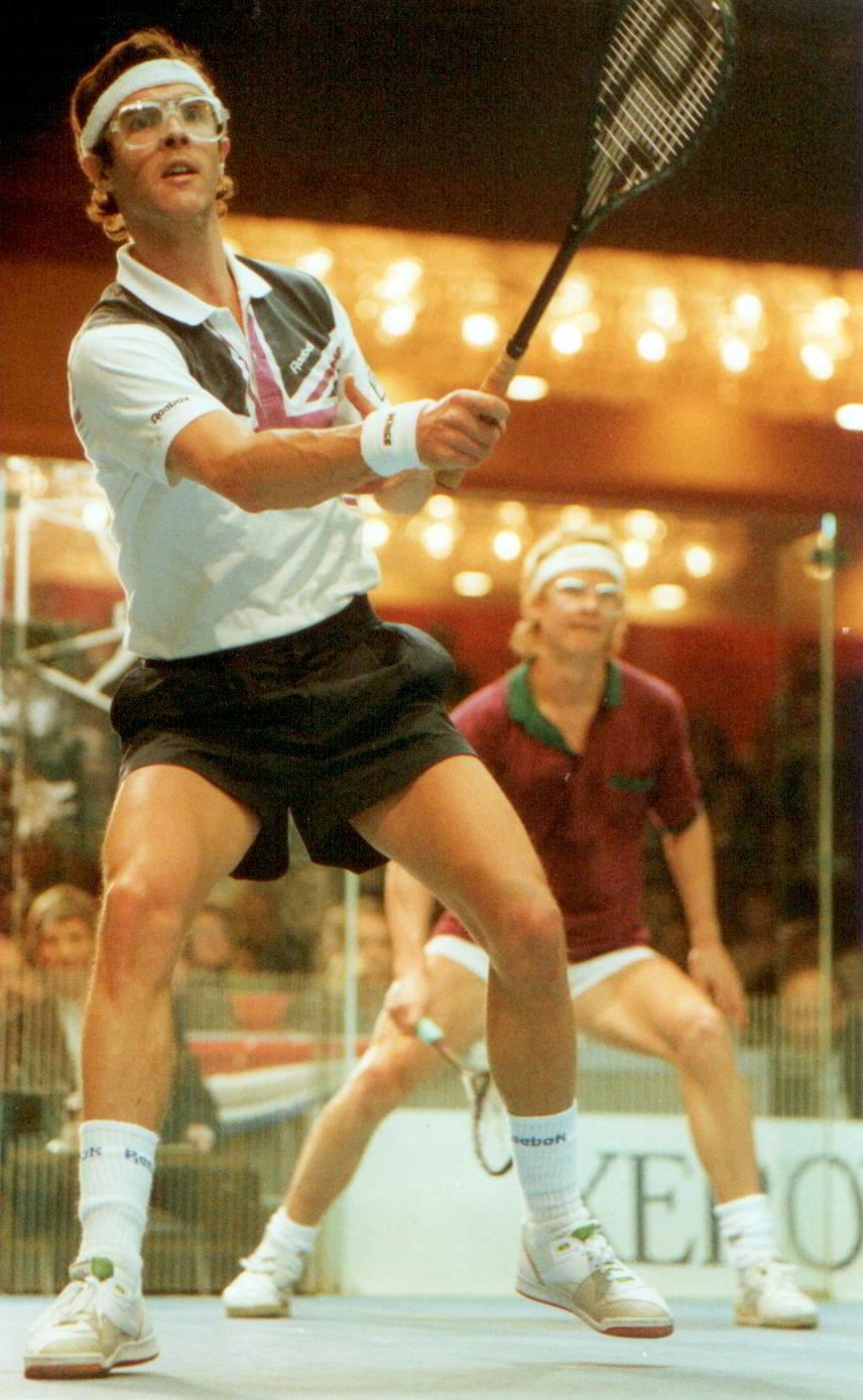

Mark Talbott looks like the ultimate surfer squashman. His players delight in extracting paragraphs from my history of squash, for they think it is hilarious that their still goofy but decidedly middle-aged coach (he turns 49 next April; his kids are in high school) was such a Dead Head (close to 100 shows), such a free spirit (quitting college), such a nut (the doghouse on the back of his pickup truck—his home on the road for a couple of seasons).

Yet, like all great champions, Talbott is intensely competitive. His green eyes still pierce when he wants to win. He scans his coaching curriculum vitae with the same bifurcation: he is alternatively sheepish about his own coaching career (it’s all luck) and bullish about Stanford squash (we are going to be top five). If he changes squash again, like he did as a player twenty years ago, well, he is more than okay with that.

The Talbott brothers worked together twice in their careers. The first time was in November 1979. Dave, almost eight years older than Mark and an abiding influence (never went to college, made a living as a squash pro and coach), answers a knock on the door of his Grosse Point home. It is Mark, supposed to be in Hartford in his freshman fall at Trinity.

“Dude, you are supposed to be in college.”

“I’m coming here,” Mark said simply.

“You are coming here? You are here.”

“That’s right.”

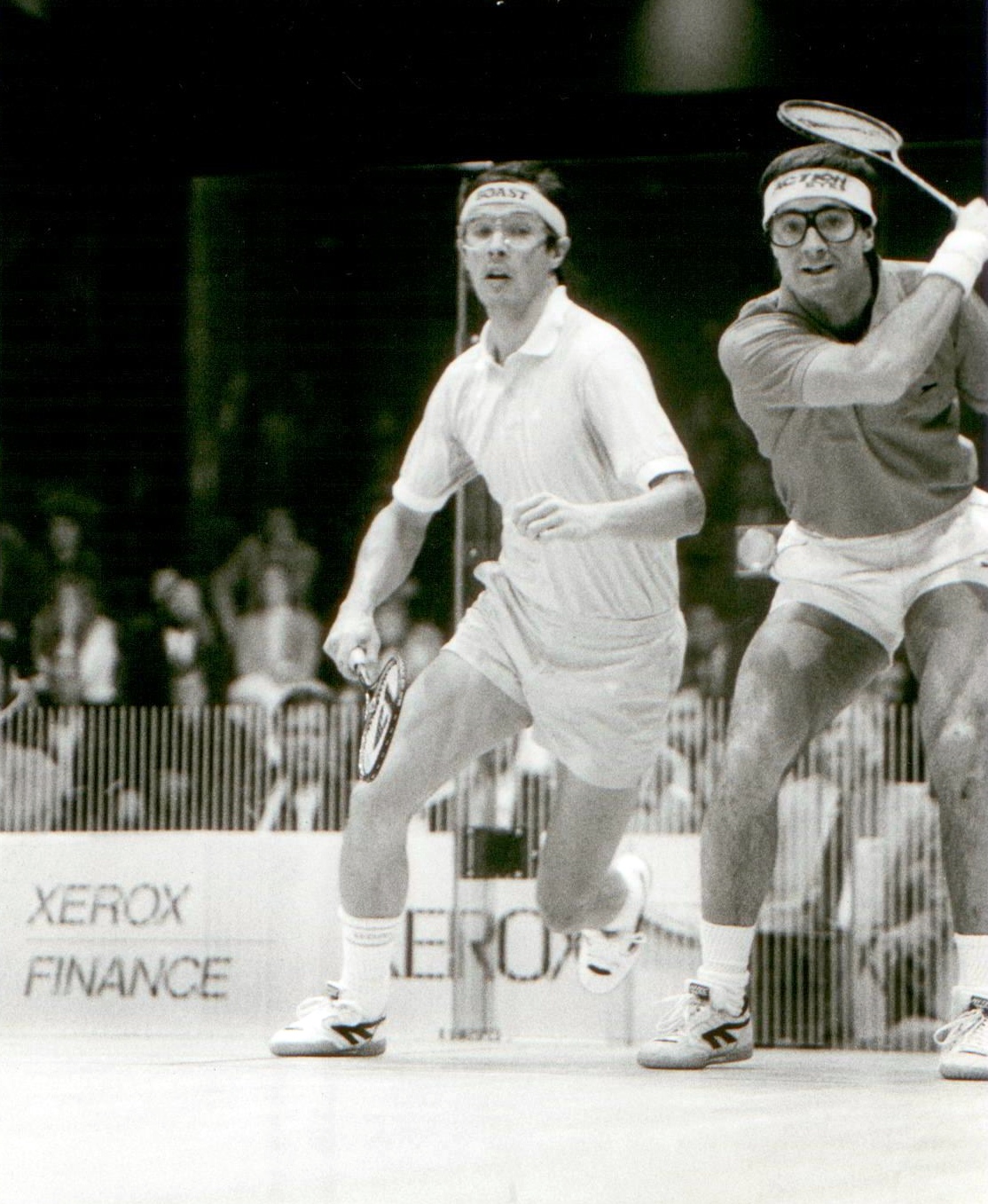

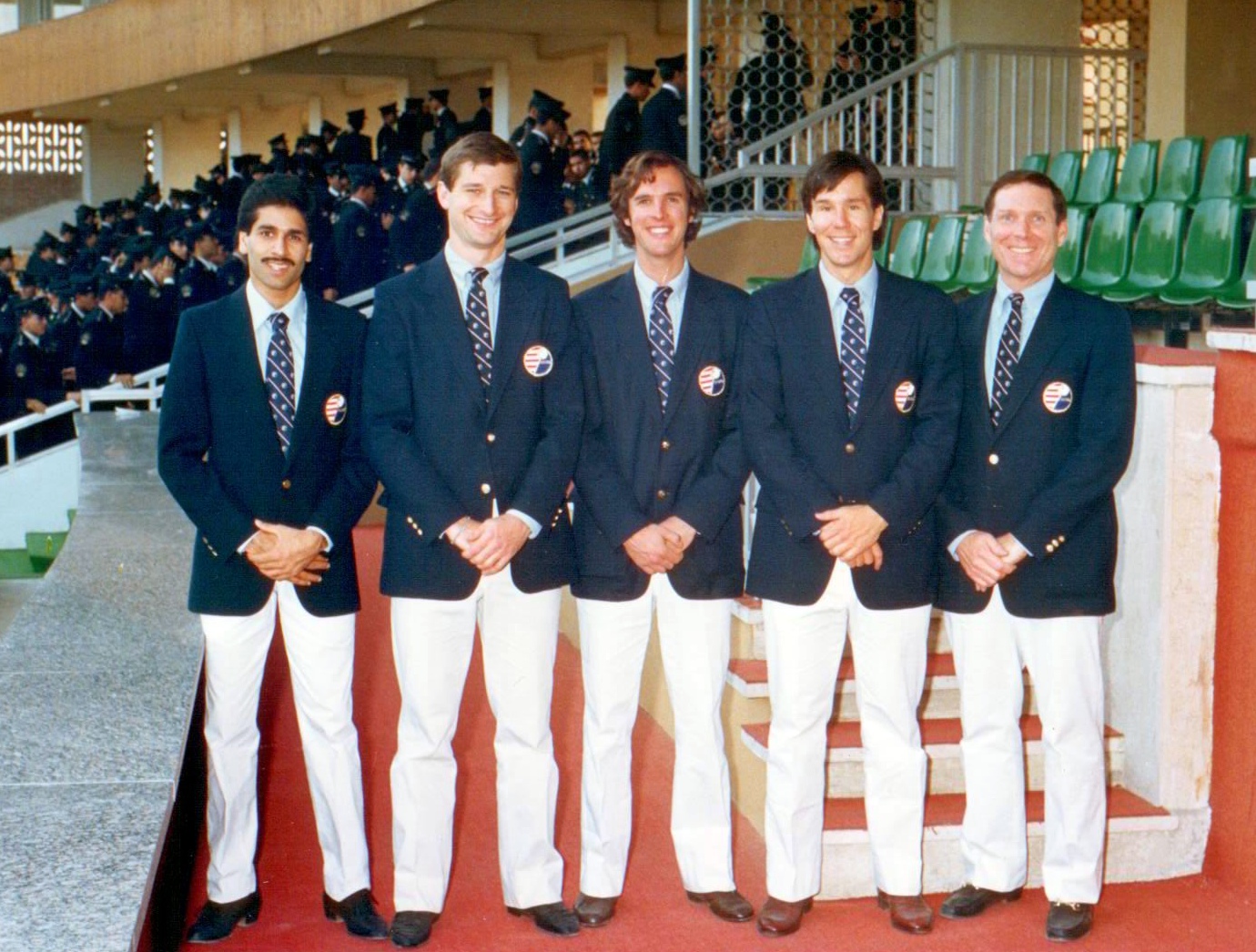

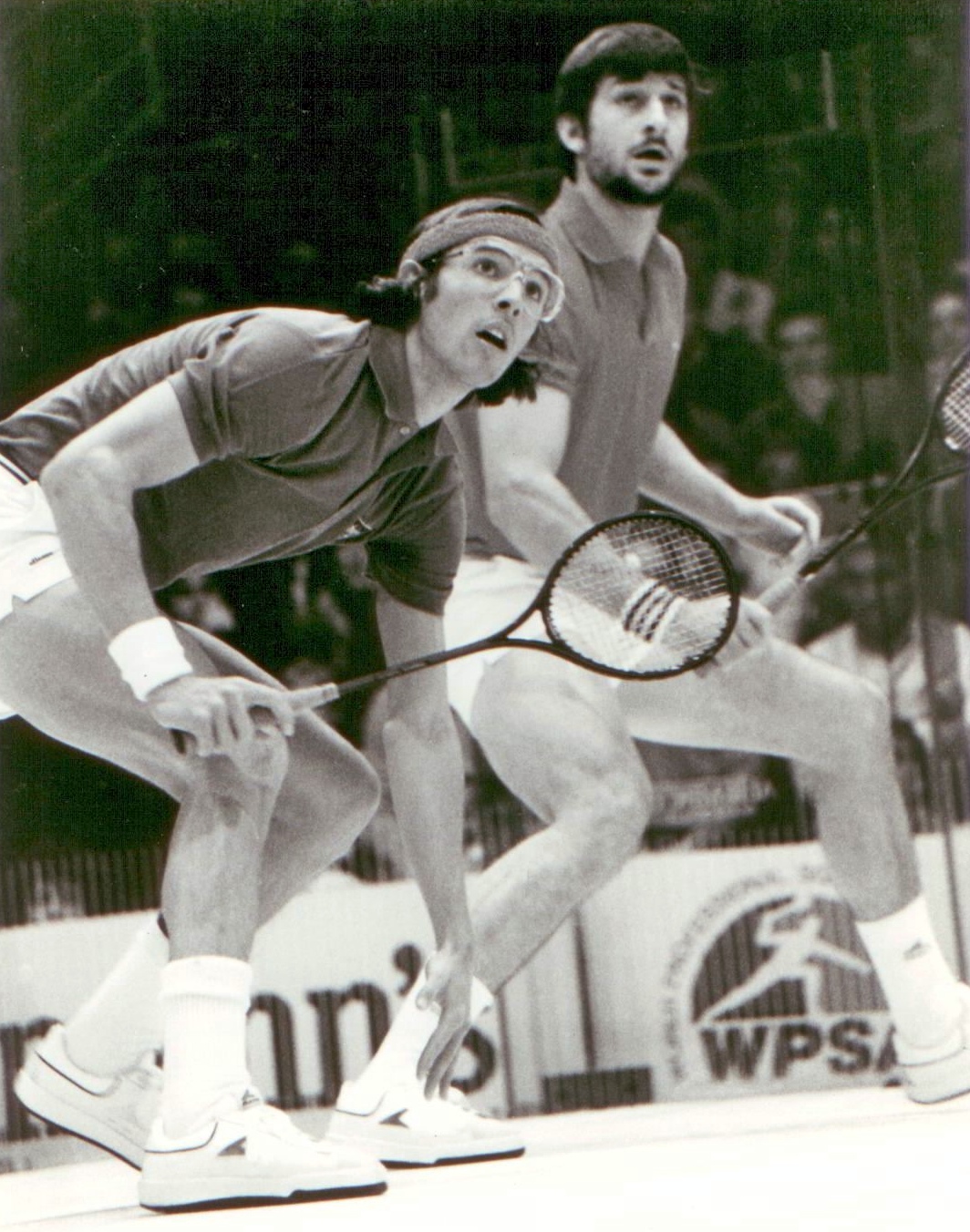

The next day Dave got Mark a job as a lifeguard at the Detroit Athletic Club, where he was the squash pro. (”CPR? No. I wasn’t the most certified lifeguard in history. But, well, I could swim.”) Mark took the bus at 6:30am each morning into Detroit and punched the time clock (”my first and last time”). In the afternoons he and Dave played squash or went on training runs or did sprints at a track near Dave’s house. In May, 1980, George Haggarty passed Mark onto some South African Jester friends in Cape Town and Durban and Mark went on his grand magical mystery squash tour—116 tournament wins, a Nicklaus-like 17 majors, greatest American ever, blah blah blah.

Twenty years later, Mark again randomly appeared at Dave’s doorstep, only this time it was the ancient oak doors of the Payne Whitney Gymnasium in New Haven. Like in Detroit, it was a bit random.

Mark’s singles career was over and his doubles career was winding down. I wrote a lengthy profile about Mark for this magazine’s predecessor, Squash News, at the time. I noted that it appeared Talbott would float and flit around the squash world forever, playing a tournament, running his famously fun Talbott Squash Academy summer camp, doing his ten-city a year Prince Residency Tour (the true ancestor of SquashBusters and the urban squash movement), an effervescent butterfly alighting on a town for awhile and then heading off.

In the summer of 1998 Dale Philippi Walker stepped down as the women’s coach at Yale, after an admirable career (national titles in 1986 and 1992), and a number of big-namers were going after the plum job. A friend and prominent coach asked Mark if he would write a letter of recommendation. Michelle, Mark’s wife, saw the letter on the dashboard of Mark’s car in Rhode Island and said, “Are you kidding? You’re taking that job.”

Mark chortled: “Wouldn’t that be great.” A few days later he went to talk with Dave about the job. “We just laughed about it and had a beer and I went home.” Two weeks later, Dave called and asked, “Were you serious about throwing your name into the hat? Some guys here heard about your visit and want you to come back down to formally interview.”

It was a done deal. The brothers Talbott at Yale. Two free spirits without a college degree running a storied program. But Dave had already been at Yale for 21 years and had national titles under his belt, and besides all the squash victories, they both had serious Eli blueblood. Their father Doug was a ‘46 and their grandfather Bud had captained the Yale football team on the day they opened the Yale Bowl against Harvard in 1914 (they lost 36-0).

The next six seasons flew by. Yale’s extraordinarily renovated squash courts—easily the best facility in the world—were about to open, and Mark helped decorate the walls with dozens of posters and photographs from the pro tour, as well as lend gravitas, in the Talbott way. Mark was a gentle recruiter. He knew all the girls from his squash camp, but he always gave the soft sell. “I remember sitting in his office on my official visit to Yale as a senior in high school,” says Michelle Quibell, the number one American junior at the time. “He said, ‘Honestly, Michelle, I want you to go where you want to. I’ll help you. You need to go where you want.’ The other coaches were often self-promoting. It was appealing that Mark was open and accepting. He’s one of the most accepting people I’ve ever met.”

Mark was a player’s coach. He let his players miss practice if they had a test coming up or if they were getting burned out. He let them pick who they would hit with at practice or what drills they’d do. Instead of trampling over him in turn, the women adored him. He played with each woman at least once a week in the morning or before or after practice. Everyone saw that he did this with the number ten player as much as the number one. “He would always play down to just above your level, so that winning was tantalizingly out of reach,” says Amy Gross, a classmate of Quibell’s. (He did this with some of the male Eli players too and was known for never giving up a game, let alone a match, to Julian Illingworth, who was about to become the reigning four-time national champion.) Van rides were infamous, for Mark would often regale them with stories from his touring days as they motored down the winter highways. “Mark’s telling stories,” the whispers went back and soon all the women were crowded in the front.

In 2003 Yale suffered two brutally disappointing defeats, a 5-4 loss to Harvard in a dual match just days after beating Harvard in the Howe Cup national intercollegiate team tournament, and a 9-0 pasting delivered by Trinity in the Howe Cup finals. The following year, it came together. Mark added five top-nine freshman recruits to the team and with a brilliant sophomore class, led by Quibell and Gross, suddenly Yale was the favorite. They didn’t disappoint, going undefeated including a tense 5-4 win over Trinity at home, with Quibell clinching it at 4-4 against intercollegiate champion Amina Helal. To ice the cake, Quibell won the intercollegiates.

A month later, Talbott was gone.

In February 2004 Maya Talbott, Mark and Michelle’s 12-year-old daughter, was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 1—the same sort of juvenile diabetes that both Clive Caldwell and Ned Edwards have. Mark and Michelle became unhappy with the treatment philosophies at the Yale Diabetes Center and in desperation hunted around for other hospitals. One day they saw an article about the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford that had what many considered the nation’s top juvenile diabetes department.

After some investigations, the Talbotts committed themselves to moving to Palo Alto. What would Mark do? He wrote a letter to Ted Leland, the director of athletics at Stanford and he called Maisy Samuelson, a Stanford junior who had founded the women’s club squash team three years earlier. At first, she thought it was a joke. Here was the famous Mark Talbott, coach of the number one ranked team, cold-calling the student who ran the team ranked last in the country and asking for a job.

Stanford squash was barely an oxymoron. There were a couple antiquated hardball courts in the DeGuerre facility when some students founded the men’s club team in 1998 and the women’s club team two years later. They got the athletic department to build two new courts in DeGuerre, but the teams were awful. One coach tended to disappear at the Howe Cup, only to be found at Foxwoods Casino. “To get players to fill out the team for our annual trip to the nationals, we’d put up flyers in dormitories and student centers,” says Samuelson. The 2005-06 co-captain, Cate Crowley, first learned about the team and the sport when he saw a flyer in a dormitory bathroom. One year, Samuelson says, she had to beg a woman from her economics class to come play No. 9 at the nationals. Most of the team only knew Mark as the nice coach at Yale who materialized with half a dozen new pairs of Prince squash sneakers when most of the team arrived at the Howe Cup with black-soled running shoes.

It was not a clean exit from his old job. Yale’s athletic department was not happy about losing Mark, especially because women’s squash had been the only Eli team to win an Ivy League title that year, let alone a national crown. He sent out a mass email to his team and then spent the rest of the day fielding phone calls and visits—”It was the hardest thing I had ever done.” The women on the team, after the initial shock wore off and the tears dried and the false blame ended (the team had made a swing through Stanford on a West Coast tour that winter), took it the best. “We said to ourselves, ‘What would Mark Talbott do? How would he handle it?’” Quibell says, “and decided to listen and be supportive.” For many the most painful moment was at the Howe Cup the following spring, when Talbott returned, wearing cardinal rather than Eli Blue, and was surrounded by a new group of adoring acolytes (some were wearing “I heart Mark” tee-shirts).

Everything fell into place—”There’s a reason for everything” says Mark. He and Michelle sold their five-story brownstone in New Haven’s Little Italy and found one of the few homes in Palo Alto under a million dollars (the real estate market was so hot there that they went from their first view of the house to closing in five days). It is a three bedroom, one bathroom, Joseph Eichler house with redwood ceilings and orange and persimmon trees in the yard. Michelle won a position for the 2005-07 seasons as the assistant prinicipal cellist in the San Francisco Symphony; most recently she won a tenure-track position in the very hip New Century Chamber Orchestra. Maya is healthy, interns at a Stanford lab and speaks three languages. Nicky, 15, has exchanged his junior tennis racquet for badminton, rock climbing, surfing, snowboarding and the trumpet.

Everything fell into place—”There’s a reason for everything” says Mark. He and Michelle sold their five-story brownstone in New Haven’s Little Italy and found one of the few homes in Palo Alto under a million dollars (the real estate market was so hot there that they went from their first view of the house to closing in five days). It is a three bedroom, one bathroom, Joseph Eichler house with redwood ceilings and orange and persimmon trees in the yard. Michelle won a position for the 2005-07 seasons as the assistant prinicipal cellist in the San Francisco Symphony; most recently she won a tenure-track position in the very hip New Century Chamber Orchestra. Maya is healthy, interns at a Stanford lab and speaks three languages. Nicky, 15, has exchanged his junior tennis racquet for badminton, rock climbing, surfing, snowboarding and the trumpet.

As for Stanford squash, it is thriving under Talbott’s leadership. The women’s team became a varsity sport in the fall of 2006, the only women’s varsity team west of the Mississippi; the men, because of Title IX, probably will not ever get varsity status. Talbott has raised $2 million to endow and support the program, which includes a $100,000 annual budget, the nation’s largest—both squads make four airplane trips east each winter. In 2006 they moved into the new Arrillaga Center for Sport & Recreation, which has seven courts (one is three-wall glass) just beyond spectacular two-story high windows that let in all that California sunshine; the old DeGuerre courts were given to the Stanford marching band.

Talbott has predictably improved the teams. The men are now ranked 21, the highest ranked club team in the nation; the women have gone from 30 the year before he arrived to 23 to 19 to 12 to seven this past year. Six recruits coming this fall will ensure that for the first time Talbott will not have a woman in the top nine who learned the game only once she got to Stanford. With that kind of experience, the team is poised to crack the top five.

And perhaps even win a national intercollegiate individual title. Two years after Talbott decided to move to Stanford, so did Lily Lorentzen. The record-setting four-time national junior champion, Lorentzen decided to transfer from Harvard just weeks after winning the national intercollegiates as a freshman (her mother and older sister are alums, and her younger sister is now there too). Lorentzen has not repeated her intercollegiate win—she was hampered in part by suddenly growing two inches at the age of twenty—but Talbott is optimistic. Like he did with Quibell and Gross, he plays a couple of times a week with Lorentzen and sees a long-term progression. “She is poised to do great things her senior year and beyond,” he says.

Talbott has ignited a squash renaissance on the West Coast. Arrillaga is the largest squash facility in California and is fueling a 75-person community program, a stronger NorCal league, more activity especially among juniors at the nearby Decathlon Club (where Jon Perry is the pro) and Pacific Athletic Club (Richard Elliott, who has also been a longtime assistant coach for the Stanford program) and even—this is 2008—an urban squash program called Xtreme Squash that Talbott started last January. Talbott has created a West Coast Championships, which has spurred club teams at the University of Washington and USC, and Cal-Berkeley is now adding a women’s club team.

One thing is for sure, Mark Talbott is not coming back east for a while. He and Michelle sold their Rhode Island home, after twenty years. For the 17th year, he has just run his summer camps, but one of the three weeks was out at Stanford rather than in Newport. The East Coast now comes to him, and more than ever Talbott is uniting the country under his rollicking, positive banner. He is designing outdoor courts for The Farm. A dozen East Coast teams have visited Stanford on winter-break tours: This season Middlebury, Denison, Harvard and Navy, among others, are scheduled to pop in.

All of those opposing coaches, you can be sure, will be very good friends.