By Richard Millman, Director of Squash, Kiawah Island Club

So you’re pretty serious about your squash and perhaps you’re thinking about your club championship or the state championship. Maybe the Grand Masters in Atlanta in December—which is about as cool a tournament as you can play in—or maybe even nationals next year.

Great! And you’ve decided to put together a fairly serious training program that includes Ghosting or Stardrills, as they are sometimes called. Well I’m with you 100 percent. I think Ghosting is a key feature of any squash training program, for anyone from age 8 to 80—no kidding!

But we need to be doing effective Ghosting—not simply running a pattern that someone showed you or that you saw in some article like this.

So what is effective Ghosting?

Well first and foremost you need to be aware of what you are concentrating on during the drill. And that should be the ball. Say what? The ball?

Well first and foremost you need to be aware of what you are concentrating on during the drill. And that should be the ball. Say what? The ball?

Yep. The Ball. One of the main errors that training athletes make when they are Ghosting is focusing on the pattern or the sequence of the Ghosting session and not the ball. But the main purpose of Ghosting is to develop some key relationships and sensitivities. Only when you have developed these skills in your Ghosting should you be thinking about using Ghosting as a physical training regime.

First and foremost you need to develop a physical, mental and emotional relationship between you and the ball. I don’t want to go Zen on you but “oneness” between your entire being and the ball is the primary goal of Ghosting. Anything going on that might distract you from developing that “oneness” is not only not useful, but is downright damaging.

For instance: Perhaps you have seen articles or diagrams propounding a certain number of steps or a line or pathway that is prescribed as the route you should take to a front or back corner. This sort of advice in and of itself is seriously damaging because it actively encourages the athlete to focus on the steps/pathway/line in isolation from and in direct opposition to the player’s focus on the ball. The net result is to produce a staccato effect where the athlete loses their “oneness” with the ball as they focus on arbitrary mechanical behaviors which don’t use the ball as the focal point of their activity. Indeed the activity itself becomes the focal point and the ball momentarily fades in importance—hardly “oneness.”

For instance: Perhaps you have seen articles or diagrams propounding a certain number of steps or a line or pathway that is prescribed as the route you should take to a front or back corner. This sort of advice in and of itself is seriously damaging because it actively encourages the athlete to focus on the steps/pathway/line in isolation from and in direct opposition to the player’s focus on the ball. The net result is to produce a staccato effect where the athlete loses their “oneness” with the ball as they focus on arbitrary mechanical behaviors which don’t use the ball as the focal point of their activity. Indeed the activity itself becomes the focal point and the ball momentarily fades in importance—hardly “oneness.”

So: Point one—whatever pattern, series, movement you engage in—make the ball your primary focus. And I mean continuously. Not just at the point of strike, but as your are recovering. And see the imaginary opponent play the next shot. Then move to the next position and start your recovery, always at one with the ball—physically, mentally, emotionally.

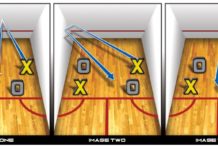

For me, a typical six shot pattern (front two corners, two half court and two back corners) might form this sort of pattern in my mind (starting from the ‘T’):

For me, a typical six shot pattern (front two corners, two half court and two back corners) might form this sort of pattern in my mind (starting from the ‘T’):

I move up to retrieve a drop in the front forehand corner. Recovering with the ball as I play a slow straight forehand float, I am half way back to the ‘T’ (always leaning toward the ball) when my opponent intercepts my straight ball with a wicked volley boast. I move foreward with the ball, shaping for a backhand straight down the wall from the front corner—but, using a little deception, I suddenly play a drop as I am moving out of the front backhand corner. My opponent picks up my backhand drop and lobs the ball cross-court to my forehand. But I move across the short line and deftly volley a high straight forehand into the forehand back corner. He is there but has to wait for the ball to come off the back wall, whereupon he tries to cross-court me to the backhand. He has hit the ball too quickly for his own recovery and I take a very early backhand volley down the wall at pace—which I can afford to do because I am in command and don’t have far to recover. He retrieves deep from the backhand with another cross court—this time much higher and slower, so I have to go all the way back to the forehand back corner and play a tight slow ball to the back. My ball isn’t as tight as it should be, and although I recover with my shot, he intercepts early and punches a volley deep to my backhand back corner.

Phew! And that’s just six shots!

Phew! And that’s just six shots!

Of course you should vary the scenarios and the patterns and really use that imagination!

The second key issue is the development of what I call: Peripheral Sensitivity.

Peripheral Sensitivity is the awareness of everything around you other than your primary focus—the ball. And Ghosting is the primary method of developing your peripheral focus. While you are doing your routine and really improving your “oneness” relationship with the ball, some other very interesting things are going to happen. For instance: Your awareness of the court and its specific features are going to become innately a part of you. If you do enough Ghosting you will automatically become aware of your proximity to anything in the court: The back wall. The ‘T’. The side walls. The middle of the court. This peripheral sensitivity will develop so that, closing your eyes, you will “see” the court perfectly—the image of your surroundings having been indelibly imprinted on your mind’s eye. This will then lead to another fascinating aspect of Peripheral Sensitivity—awareness of where your opponent is and where your opponent isn’t. In other words, the spaces on the court and gaps in your opponent’s defense on a moment by moment basis.

Peripheral Sensitivity developed by organized, effective Ghosting will lead to enormous improvements in your effective and economic court coverage and organization, from simply being aware of where you are in relation to the back wall and when the ball will strike it (thereby enabling you to prepare early) to an almost “eyes-in-the-back-of-your-head” prescient understanding of where the opponent is. In fact if you Ghost effectively, you may almost develop a supernatural ability to glide spookily around the court, using relatively little of your corporeal resources. Whoa! Now I’m getting spooked!

Seriously though: Get out and Ghost! But do it effectively and you will be amazed at how you develop as a connected and sensitively aware squash player!

Next month: The Values and Dangers of traditional lore in squash—towards a thinking game.

Skill Level Tips

Simple practice tips for 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0 players

3.0

Ghosting is good for everyone. Follow the advice in the LessonCourt article and try the six shot pattern ( front forehand – front backhand – midcourt forehand – midcourt backhand – back corner forehand – back corner backhand ) for 30 seconds on, and then 30 seconds rest.

Go at a rate that allows you to maintain your balance the whole time. When you have done enough sets that you feel you could do one more before you are exhausted—stop and don’t do the last one. Come back the next time and do the same. Always stop when you think you could do one more. In the end you will do more that way and you’ll never be frightened of coming back.

4.0

Try and build up to “one minute on, one minute off” Ghosting sessions. Do it with a partner so you can alternate and make sure you really encourage each other. Try and vary the types of shots you are thinking about. Follow the 3.0 tip about finishing when you feel you could do one more. And don’t forget—you might be able to do more than your partner or vice-versa. That’s OK, just finish when you could do one more.

5.0

So you have been Ghosting for a while. And you have used the advice in the Lesson Court article about “oneness” and Peripheral Sensitivity. Now start varying the recovery times you use. Instead of one minute on, one minute off, try using your Ghosting in different areas of your training—like for your short burst anaerobic work. Perhaps try 30 seconds on, 15 seconds off. Over time build up to 45 seconds on, 15 seconds off. Before you do this, always make sure you are medically fit enough to work at this intensity.

This type of short recovery Ghosting can really help you through crises in intense competition. Good luck!