By James Zug

Hashim Khan, who I think can fairly be described as the greatest squash-racquets player of all time, made his American debut in the winter of 1954.

Hashim Khan, who I think can fairly be described as the greatest squash-racquets player of all time, made his American debut in the winter of 1954.

Hashim Khan, may his tribe increase, completely changed the course of events in the game of squash racquets.

The more I think about it, the more firmly convinced I am that the greatest athlete for his age the world has ever seen may well be Hashim Khan, the Pakistani squash player.

That was how Herbert Warren Wind led off his three epic articles on squash in the New Yorker, in 1973, 1978 and in 1985. Being the New Yorker, the articles were rigorously fact-checked, and all hyperbole was stricken with a red pen. These three sentences were true then and are true today.

Yet, Wind and the New Yorker got his birth date wrong. There is no birth certificate for Hashim Khan. Ned Bigelow, the founder of the United States Open and the man responsible for bringing Hashim to the US and thus revolutionizing our game, made a trip to Pakistan in the 1960s solely to dig up the elusive piece of paper. But the Northwest Frontier Province of the Raj four decades before independence did not focus on record-keeping, and after days of searching Bigelow declared that there was no extant proof of Hashim’s arrival in this world (most of Hashim’s children don’t know their birth date either). Hashim grew up thinking he was born in 1914. When he was first approached, in 1951, about coming to England to play in the British Open, he thought they would not let him play in the tournament if they knew he was 37. So he made himself 35, with 1916 as a birth date. A few years ago he changed it back to 1914. Many people believed he was born even earlier, in 1910 or 1912. Regardless, Hashim is now sticking to 1914, which makes the first of July 2004 his 90th birthday.

Many happy returns, indeed, for whenever he was born, Hashim can look back on a legacy greater than anyone else in the history of squash.

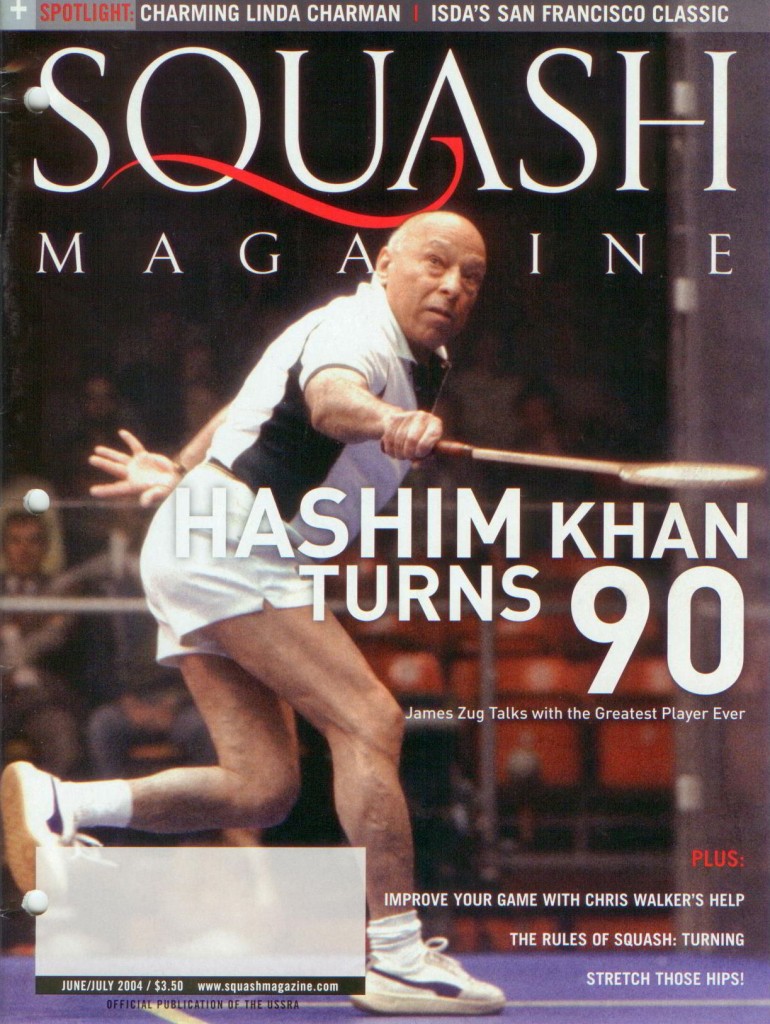

It was sensationally improbable. He was born in an obscure village of a country with fewer than 10 courts. He grew up playing barefoot in the dusty open air. He looked unlike any other world-class athlete. He was barely five feet four. He had a bald pate, round head and tea-colored skin, which made him look strikingly similar to Yul Brenner in “The King & I” or an aging Pablo Picasso. “His legs were short and on the spindly side,” wrote Wind, “and, particularly since he was barrel-chested and had the suspicion of a potbelly, he seemed curiously top-heavy.” He was shy and painfully polite—to this day he insists on opening doors and leaving the court last. He was nothing like other Khans like the ebullient rapscallion Mohibullah or the chain-smoking Roshan. His English was never good. (Even now, after 44 years of residence in America, he still speaks with a heavy Peshawar accent and with his infamous “Hashim-speak” pidgin, article-and-past-tense-less phrasing.) He was a Muslim who neither drank nor smoked. He was a Pathan, who believed in gender-specific roles and favored arranged marriages like his own, in which he first saw his wife’s face on their wedding day.

A fair amount of Hashim’s fame came from his game. On the court, he was genius. He had such blinding speed that no ball was truly out of reach. He was unconscionably fit, after his years of “Hashim v. Hashim” matches. Wind wrote that after three games in the finals of the 1954 US Open, Henri Salaun, a notoriously fit player, “could barely drag himself to and through the door leading from the court, whereas Hashim, for all his years [he was almost twice Salaun’s age] wasn’t even breathing hard.” He beat people with embarrassing ease. In the finals of the 1951 British Open, he toyed with the great stylist Mahmoud El Karim, 9-0, 9-0 in the last two games. In 1952, a cocky Australian went up 7-0 in the first game and began showboating; Hashim hit nine straight nicks.

His record is silly sick. He won seven British Opens, the last at age 44; three US Opens, the last at age 49; three Canadian Opens, an Australian Open, eight Scottish Opens, five British Professionals, and three US Professionals. Just imagine the totals if he had been 20 when he arrived in London. Just imagine what no one but the unwitting, gin-soaked members of the Peshawar Club saw: Hashim Khan in his prime.

But what makes Hashim a legend, especially in America, is not his titles. In 1960, six years after his triumphant first visit to the US, Arthur Sonneborn, a retired engineer, persuaded Hashim to move from Peshawar to Detroit and take a job at the Uptown Athletic Club. The club was awkwardly humble, not a Merion or Heights Casino or University Club, but a couple of courts near the Ford factory in a second-tier squash city. They did not even have a proper pro shop, so the best player in history could be found stringing racquets by hand, without a stringing machine, sitting on a thin wooden bench in the locker room.

Despite the handicaps of culture, language and location, Hashim instantly transformed the American scene. He forced restrictive clubs to reexamine their practices, with one flash of his impish smile. He cooked curries for friends and once disappeared inside a Pakistani restaurant and reappeared 10 minutes later in an apron with a dish he had personally cooked. He was a magnetic coach who attracted hundreds of acolytes. People came from around the world to take lessons. A local cardiologist, a B player, took a lesson every day Hashim was in town: “Watch ball, walls don’t move. Hurry to go to the ball, then take time to hit. You must be conditioned to play the last point of the fifth game.” Somehow, he kept you in the game until he could call out, “14-all, world championship point,” and then get a nick.

“It is always a thrill for me to play with him, because he’s my dad and because he’s Hashim Khan,” says Charlie Khan. “You just pick up on his energy. He’s got that twinkle in his eye and you get mesmerized. The way he hits the ball and moves on the court, it can put you in a trance. He’s not hitting the ball, he’s telling the ball where to be. He and the ball are in communication. There’s nothing quite like it.”

Using his position as the first squash celebrity in the country—the first time a camera took photographs from the front of the court, by remote, was for a Hashim match in 1954—he evangelized the game. Each year Hashim flew to tiny squash clubs in the hinterlands—Louisville; Charleston, West Va.; Dallas—and opened new courts or gave clinics. These weekends did more than anything else to convert Americans to the game of squash. He brought over his extremely talented extended family, most of whom stayed: Mo and Gul, his nephews; and 11 of his 12 kids: Sharif, Dilshad (she stayed in Pakistan), Gulmast, Aziz, Noshad, Charlie, Sam, Yasmin, Shaukat, Muhammed, Shaheena and Subhania. (He and Mehria also lost four children in infancy.) Add in his brother Azam and cousin Roshan and Roshan’s son Jahangir, and you have 25 of the first 30 winners of the North American Open. But more importantly, you have long, memorable coaching tenures, whether Mo at the Harvard Club in Boston or Charlie and Sam in St. Louis.

In 1973 Hashim went even further off the beaten path. His wife, Mehria, suffered from a variety of ailments including rheumatism and arthritis and needed a drier climate; Uptown was struggling; he wanted to live somewhere that looked a little more like the Khyber Pass. “I heard through the grapevine he wanted to move,” says Hugh Tighe. The incoming president of the Denver Athletic Club, Tighe was a handball and badminton player. But as the owner of a Chrysler dealership in Denver, he spent time in Detroit and had heard of the great Hashim. Tighe called the Uptown Club. “Hashim said, ‘You bring gym shoes and shorts and I give you a taste of squash Khan way.’ And so we played and he almost killed me—in that marvelous, Hashim way. We flew him out to Denver and the rest of the story is still going on. Of course, I like to say that when we signed his contract, he was 12 years older than me and now he’s just 10 years older. So I’m gaining on him.”

Denver skyrocketed. The DAC jumped from two dozen players to hundreds. Other clubs in Colorado prospered. And the West finally was on the map. “People have heard of the DAC and Denver squash and Colorado squash because of Hashim,” says Tighe. “Everywhere I go people will say, ‘Wow, you’re a guy who plays with Hashim?’ It is like playing golf regularly with Jack Nicklaus. It gives Denver instant credibility.”

Although he retired in the late 1980s, Hashim is still the majordomo in Denver. “Hashim is amazing,” says DAC pro John Lesko. “I get three or four phone calls a week from people wanting to talk to him, get an autograph. I get mail for him all the time. This is his home away from home and the one place everybody knows they can find him.”

Current national champion Preston Quick, who grew up at the DAC, says: “Hashim didn’t seem like a world-famous celebrity when I was a kid until I started going away to tournaments. The first thing people would say to me was, ‘Denver? Do you know Hashim Khan?’”

Now a nonagenarian, Hashim’s life is pretty simple. He keeps in close touch with his family (he has no idea exactly how many great grandchildren he has, but guesses it is more than a hundred). He is meant to be the great patriarch: His first name comes from the great grandfather of the Prophet (his last name is, as Wind says, “more an ethnic identification than a family name.”) He goes home to Pakistan usually every year or two, but is an American citizen and plans to be buried in a cemetery in Denver. He and Mehria have lived in the same, ranch-style brick house in Aurora, a middle-class suburb southeast of Denver, for the past 30 years. It is decorated with numerous photographs and trophies, everything from his US Squash Hall of Fame plaque from 2000 to his medal for winning the British Open in 1951. Green oxygen bottles stand in the front hallway, a dispiriting sign of his wife’s declining health.

Hashim’s schedule is simple. He prays five times a day (he has made the pilgrimage to Mecca three times) and on Fridays goes to his mosque. He putters around his house, fixing things; his project this spring was to repair the floor of the front porch. A couple of times a week he gets in his brown Honda and, with his head invisible from behind, drives for 25 minutes past the state capitol to the Denver Athletic Club. He has the first locker in the first row in the members-only locker room at the DAC. He changes and walks past a bulletin board stuffed with clippings from his career, the Hashim Khan Court and the Hashim Khan Trophy Room, which has a stunning array of examples of Hashim’s fame: honorary memberships in clubs on six continents, the North American Open trophy, last played at the DAC in April 1995, and, most poignantly, the 2003 SL Green Trophy won by DAC member Preston Quick.

Even with a bad knee that limits his mobility, he plays doubles twice a week with a group of friends, including 92-year-old Frank McGlone and an 80-year-old, Judge Cisneros. He also plays singles, especially when training for the British Open vintage tournament. “If you put the ball on his racquet,” says Quick, “he’ll put it away. Every time.” And he helps out the DAC pros, Anne and John Lesko, sometimes coming to their Sunday morning junior clinics that are sponsored by the Hashim Khan Foundation.

Every first of July the DAC throws a little birthday bash for Hashim. This year they hope to close off Glenarm Street and throw a block party and have the mayor of Denver, a DAC member, declare it Hashim Khan Day. For America, though, it has been the Hashim Khan Half-Century, We are all in his tribe and, as Wind said, may his tribe increase.